Translate this page into:

Imaging of Mechanical Cardiac Assist Devices

Address for correspondence: Dr. Daniel Ginat, Department of Imaging Sciences, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester, NY 14623, USA. E-mail: ginatd01@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Diagnostic imaging plays an important role in the assessment of patients with mechanical cardiac assist devices. Therefore, it is important for radiologists to be familiar with the basic components, function, and radiographic appearances of these devices in order to appropriately diagnose complications. The purpose of this pictorial essay is to review indications, components, normal imaging appearances, and complications of surgically and percutaneously implanted ventricular assist devices, intra-aortic balloon pumps, and cardiac meshes.

Keywords

Cardiac mesh

Impella

imaging

intra-aortic balloon pump

ventricular assist device

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure is a major cause of morbidity and mortality despite medical treatment. Over the last half century, a variety of mechanical cardiac assist devices have been developed. The main types of mechanical ventricular assist devices currently used include surgically implanted ventricular assist devices, percutaneous ventricular assist devices, intra-aortic balloon pumps (IABPs), and cardiac meshes which are summarized below:

-

Surgically implanted ventricular devices are mainly used for the treatment of chronic end-stage or acute heart failure, and as “bridge to transplant”, “bridge to recovery”, and “destination therapy” for patients who are not transplant candidates. Newer models are portable and intended for chronic outpatient use. The use of these ventricular assist devices has led to improved survival.

-

Percutaneous ventricular assist devices are used for rapid, but short-term restoration of hemodynamic stability in patients with cardiogenic shock, during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention procedures, and for postcardiotomy low-output syndrome.[1–3]

-

The main indications for IABPs include circulatory support after myocardial infarction, malignant arrhythmia refractory to pharmacological treatment, acute recurrent left ventricular dysfunction, and acute occlusion of a major coronary artery during catheterization.[4–6] The goals of IABP treatment are to increase the myocardial O2 supply and decrease the myocardial O2 demand.

-

The heart mesh is a relatively novel device that is intended for the long-term treatment of heart failure by preventing ventricular remodeling and improving ventricular function.[7]

Imaging is used to verify proper positioning of the devices and to assess for complications. Radiographs are generally used for initial screening, while CT is used to better delineate the device components and their anatomical relationships. Furthermore, the hemodynamic influences of mechanical cardiac assist devices can be appreciated on Doppler ultrasound. Therefore, it is important for the radiologist to be familiar with the imaging features of these devices. In this article, the components of the main types of mechanical cardiac assist devices are described and their imaging appearances are illustrated.

Surgically implanted ventricular assist device

Several models of surgically implanted ventricular assist devices are commercially available including Jarvik 2000, HeartMate, Abiomed, Levitronix, and Novacor. These include first-generation pulsatile and second-generation nonpulsatile pump mechanisms, which produce a continuous flow [Figure 1]. These hemodynamic modulations preclude accurate Doppler ultrasound velocity measurements and necessitate temporary cessation of the device if feasible.

- Ventricular assist device hemodynamics. (a) Doppler ultrasound image shows the pulsatile flow in an old-generation device. (b) Doppler ultrasound image shows the continuous flow in a new-generation device.

Surgically implanted ventricular assist devices comprise a pump mechanism connected to an inflow and an outflow cannula for the passage of blood at either end [Figure 2]. A battery pack powers the pump via a driveline that is tunneled through the subcutaneous tissues of the chest and sometimes a portion of the peritoneum. The driveline contains an electric cable and in some cases, an air line.

- Ventricular assist device components on radiograph and CT. (a) Frontal radiograph shows the driveline (arrow), pump (*), and conduits (arrowheads) that comprise a left ventricular assist device. (b) Axial CT images at two different levels show the components (labeled) of biventricular assist devices.

Ventricular assist devices can be configured as left (LVAD), right (RVAD; uncommon), or biventricular (BIVAD). With LVAD, the outflow conduit attaches to the aorta and the inflow conduit attaches to the left ventricle. In contrast, with RVAD, the inflow cannula attaches to the right ventricle, and the outflow cannula attaches to the pulmonary artery. BIVAD includes both RVAD and LVAD devices.

The imaging appearances of ventricular assist devices vary depending upon the model. For example, the Novacor and HeartMate cannulae are composed of silicone, which is not discernible on radiographs and require CT for evaluation.[89] Therefore, CT is the standard of reference for assessing ventricular assist device cannula and pump components and positions.[8] MRI is contraindicated for patients with ventricular assist devices.[10]

Complications related to ventricular assist devices include kinking of the outflow cannula causing obstruction, infection, hemorrhage, pericardial tamponade, thrombosis, aortic valve stenosis or regurgitation, and right heart failure.[1011]

Hemorrhage after ventricular assist device implantation is common and usually occurs within the pericardial space, pleural space, and around the conduits [Figure 3]. Hemorrhage appears as high-density fluid collections, often heterogeneous. A small amount of hemorrhage may not be of clinical significance. However, when hemorrhage is profuse, hypovolemia can result, requiring transfusions.

- A 53-year-old female with hemorrhage following BIVAD insertion. (a) Axial CT images show heterogeneous hemothorax (*), (b) hemopericardium (*), and (c) hemorrhage surrounding the pump and conduits (arrowheads).

The incidence of infection ranges from 14% to 72%.[10] Superficial driveline infections are the most common, but the least severe type of device-related infection. These appear as cylindrical fluid collections and fat-stranding surrounding the driveline [Figure 4]. In contrast, deep infections are serious, but less common complications. Beam-hardening artefacts can obscure deep infections adjacent to the pump. Persisting or enlarging fluid collections indicate periprosthetic infection, whether or not the patient develops fever or leukocytosis [Figure 5]. Antibiotic-impregnated beads are sometimes applied to the VAD pump pocket after the explantation of infected hardware.[12] The beads appear as high-density ovoid structures posterior to a new pump [Figure 6].

- Two patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa driveline infections. (a) Axial CT image shows an abscess (arrow) surrounding the driveline in the subcutaneous tissues. There is also overlying skin thickening, compatible with cellulitis (arrowhead). (b) Axial CT image shows an abscess (arrowhead) around the driveline in the peritoneum.

- A 46-year-old male with Staphyloccocus aureus conduit infection. (a) Baseline axial CT image shows trace fluid (arrows) surrounding the conduits. (b) Axial CT obtained 2 months later shows an interval increase in fluid (arrows) surrounding the conduit.

- A 72-year-old female with a history of deep pocket infection treated with VAD exchange and antibiotic beads. Axial noncontrast CT image shows high-attenuation antiobiotic beads (arrowheads) beneath the new pump (arrow).

Thromboembolism is another common complication of ventricular assist devices. Thrombi can occur in the ventricle, usually extending into the inflow cannula, or within the outflow cannula [Figure 7]. These appear as nonenhancing low-attenuation masses adherent to the cannula or ventricular walls. Thromboembolism is more common with pulsatile flow devices than continuous flow devices due to greater stasis of blood.[10]

- A 57-year-old male with thrombosed Right Ventricular Assist Device (RVAD). Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows thrombosis of the pulmonary artery RVAD conduit (arrow). However, the proximal portion is patent (arrowhead).

Percutaneous ventricular assist device

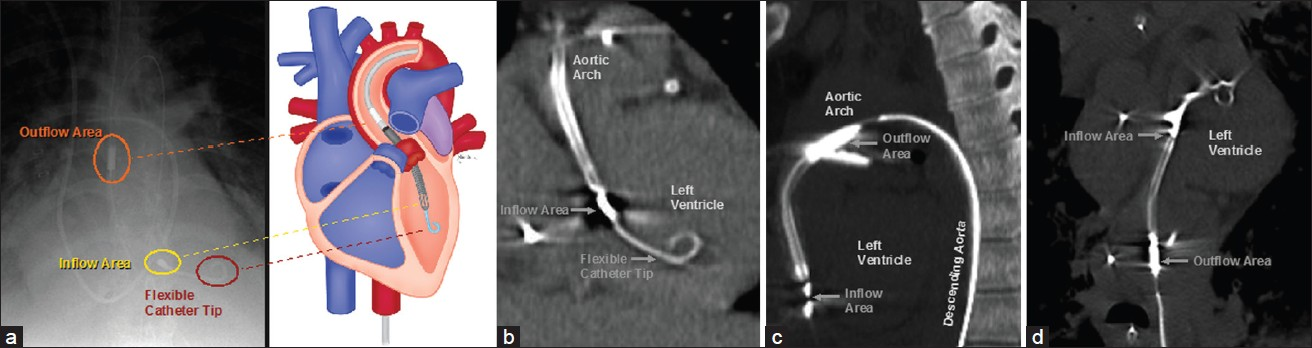

Percutaneous ventricular assist devices are catheter-based circulatory support systems that consist of an intravascular micro-axial pump mechanism [Figure 8]. For example, Impella 2.5 (Abiomed Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) can augment cardiac output by 2.5 L/min at a maximum rotation of 51,000 rpm (s). The devices are usually introduced into the heart and aorta via a femoral artery approach. The distal tip of the percutaneous ventricular assist device is coiled and lies within the left ventricle [Figure 9]. The inflow area is also positioned within the left ventricle and serves to draw blood from the left ventricle toward the arch of the aorta, where the outflow area is located. The outflow area exhibits the rotating pump mechanism that propels blood through the aorta. Multiplanar reformatted CT images are particularly useful for delineating the entire course of the device. The percutaneous ventricular assist system provides excellent short-term hemodynamic support. Major complications occur in 20% of cases, including periprocedural myocardial infarction and hemolysis in 10%.[8]

- Photographs of the Impella 2.5 circulatory support system components (reproduced with permission from Abiomed).

- Impella 2.5 components on radiograph and CT. (a) Frontal radiograph and the corresponding diagram show components (labeled) of the percutaneous ventricular assist device with respect to anatomic structures. (b) Coronal MIP, (c) sagittal MIP, and (d) vessel trace CT images demonstrate the main parts (labeled) of the percutaneous ventricular assist device in normal positions.

Intra-aortic balloon pump

The Intra-aortic Balloon Pump (IABP) is a percutaneously inserted cardiac support device that exploits the principle of counterpulsation. Inflation and deflation of the balloon are synchronized to the patient's cardiac cycle. The IABP deflates during systole in order to decrease the afterload and inflates during diastole to increase coronary artery perfusion [Figure 10].[13] This produces a characteristic waveform on Doppler ultrasound [Figure 11].

- The IABP inflated within the aorta during diastole and deflated during systole.

- IABP carotid ultrasound waveform. Effects of the IABP on the cardiac cycle include unassisted systole, diastolic augmentation, and assisted aortic end-diastole (labeled).

The IABP consists of a catheter with a 4-mm rectangular, radiopaque marker distally and a balloon that can be visualized during diastole as a tubular lucency that usually measures 25 cm in length, when filled with either He or CO2 [Figure 12]. The tubular radiolucency should not be confused with intra-aortic air that can occur with mesenteric ischemia.[14] The radiopaque marker is optimally positioned at the level of the carina, which corresponds to about 2–4 cm distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery.[15] Although IABPs are MRI compatible, these devices may have to be paused during the scan.

- IABP components on imaging. (a) Frontal radiograph and (b) curved reformatted CT image show the radiolucent inflated balloon (arrows) and distal radiopaque marker (arrowheads).

Complications related to IABPs occur in about 29% of cases, which is why routine radiographic surveillance is performed.[4] IABP malpositioning is perhaps the most frequent complication [Figure 13]. The superior migration of the IABP can occlude the left subclavian artery, resulting in limb ischemia. Conversely, inferior IABP malposition can lead to visceral complications such as mesenteric ischemia and less commonly hepatic failure.[1617] Predisposing factors may be anatomic and may include balloon length mismatch and spinal deformities.[16] Aortic dissection occurs in about 1% of cases of IABP insertion.[1819] This is recognized on contrast-enhanced CT by the presence of a low-attenuation linear flap with the IABP positioned within the false lumen [Figure 14].

- Malpositioning of the IABP in two different cases. Frontal radiograph shows the radiopaque marker (arrowhead) positioned at the level of the aortic arch, far cranial to the carina (arrow). (a) Frontal radiograph shows the radiopaque marker (arrowhead) positioned in the mid-abdomen. (b) Axial CT shows partially inflated IABP (arrow) at the celiac artery (arrowhead) level.

- A 68-year-old man with back pain following IABP insertion. Axial CT image shows aortic dissection (arrowheads). The IABP (arrow) is within the false lumen.

Cardiac mesh

The cardiac mesh, such as Paracor HeartNet (Paracor Medical Inc. Sunnyvale, CA, USA), is an elastic Nitinol ventricular constraint device that provides continuous support.[7] The device is inserted around the epicardium and envelopes the right and left ventricles like a mesh “bag” [Figure 15]. HeartNet is difficult to discern on radiographs, but can be readily evaluated on CT, particularly with multiplanar reformatted images and maximum intensity projection. These devices appear as mildly radiodense tubular mesh structures that closely embrace the ventricles. There is no significant streak artefact produced. Another variety of cardiac mesh is the CorCap Cardiac Support System (Acorn Cardiovascular Inc, St. Paul, MN, USA), which is composed of polyester mesh.[7] Similar to Paracor HeartNet, CorCap also encompasses the right and left ventricles, but is relatively radiolucent.

- A 61-year-old man with a history of heart failure, ejection fraction of approximately 10–15%. (a) Axial and (b) coronal CT images show metallic mesh that envelops the ventricles (arrows). A pacemaker is also noted (*).

The cardiac mesh can be implanted successfully in most patients and be used in conjunction with surgically implanted left ventricular assist devices for patients with severe, progressive heart failure.[20] The cardiac mesh device appears to be conducive toward reverse modeling of the heart.[2122] Although arrhythmias occur in 27%, epicardial laceration in 4%, and empyema in 2% of patients following implantation surgery, significant complications related to the cardiac mesh are uncommon.[2122] In particular, adhesion formation with the cardiac mesh appears to be negligible.[20]

CONCLUSION

With the increasing use of circulatory support mechanisms, diagnostic imaging plays an important role in the management of patients with mechanical cardiac assist devices. Radiologists should be familiar with the basic components of these devices and their corresponding radiographic appearances in order to appropriately diagnose potential complications.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2011/1/1/21/80373

REFERENCES

- The Impella ventricular assist device: Use in patients at high risk for coronary interventions: Successful multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention in a 62-year-old high-risk patient. 2011;12:69. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2011;12:69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous ventricular assist devices for cardiogenic shock. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2008;5:163-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of Impella Recover 2.5 left ventricular assist device in patients with cardiogenic shock or undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention procedures: Experience of a high-volume center. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2008;56:391-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vascular complications of the intra-aortic balloon pump. Am J Surg. 1992;164:517-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- The need for intra aortic balloon pump support following open heart surgery: Risk analysis and outcome. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Card Surg. 2008;23:79-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical remodeling of the left ventricle in heart failure. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;16:72-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- A prospective feasibility trial investigating the use of the Impella 2.5 system in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (The PROTECT I Trial): Initial U.S. experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:91-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complications in patients with ventricular assist devices. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2008;27:233-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of infected left ventricular assist device using antibiotic-impregnated beads. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:554-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haemodynamic effects of the use of the intraaortic balloon pump. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2007;48:346-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computed tomography appearance of an intra-aortic balloon pump: A potential pitfall in diagnosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:231-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The carina as a useful radiographic landmark for positioning the intraaortic balloon pump. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:735-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Visceral arterial compromise during intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation therapy. Circulation. 2010;122:S92-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute ischemic hepatic failure resulting from intraaortic balloon pump malposition. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17:492-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vascular complications of the intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation. Angiology. 2005;56:69-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vascular complications of the intraaortic balloon pump in patients undergoing open heart operations: 15-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:645-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful implantation of a left ventricular assist device after treatment with the Paracor HeartNet. ASAIO J. 2010;56:457-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Initial United States experience with the Paracor HeartNet myocardial constraint device for heart failure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:204-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Worldwide surgical experience with the Paracor HeartNet cardiac restraint device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:188-95.

- [Google Scholar]