Translate this page into:

Identification of Cardiac and Aortic Injuries in Trauma with Multi-detector Computed Tomography

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Blunt and penetrating cardiovascular (CV) injuries are associated with a high morbidity and mortality. Rapid detection of these injuries in trauma is critical for patient survival. The advent of multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) has led to increased detection of CV injuries during rapid comprehensive scanning of stabilized major trauma patients. MDCT has the ability to acquire images with a higher temporal and spatial resolution, as well as the capability to create multiplanar reformats. This pictorial review illustrates several common and life-threatening traumatic CV injuries from a regional trauma center.

Keywords

Aortic injuries

cardiovascular

multi-detector CT

trauma

INTRODUCTION

Blunt and penetrating cardiovascular (CV) injuries are associated with a high morbidity and mortality. Rapid detection in a trauma patient may improve survival. Multi-detector computed tomography (MDCT) has increased the recognition of CV injuries in imaging of major trauma patients. MDCT has improved temporal and spatial resolution of images, allowing for improved quality of images and multiplanar reformats (MPRs) in a poly-trauma patient.[1] This pictorial review of traumatic cardiac and vascular injuries presents cases from a regional trauma center.

CARDIAC INJURIES

CV injuries are the second most common cause of traumatic death after central nervous system injuries and can be caused by penetrating or blunt trauma.[12] Penetrating injuries to the heart are lethal and are associated with a survival rate of approximately 6%.[1] Blunt cardiac injuries are associated with mortality rates ranging from 41 to 89%.[3] Various mechanisms may be involved in blunt cardiac injuries, including deceleration, blast, concussive, direct, and indirect forces.[2] MDCT allows for evaluation of cardiac injuries with a high sensitivity for pneumopericardium, pericardial effusion, pericardial or myocardial lacerations, and cardiac luxation.[4]

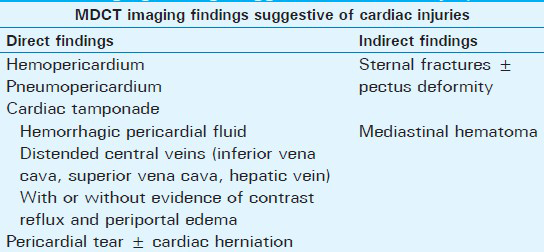

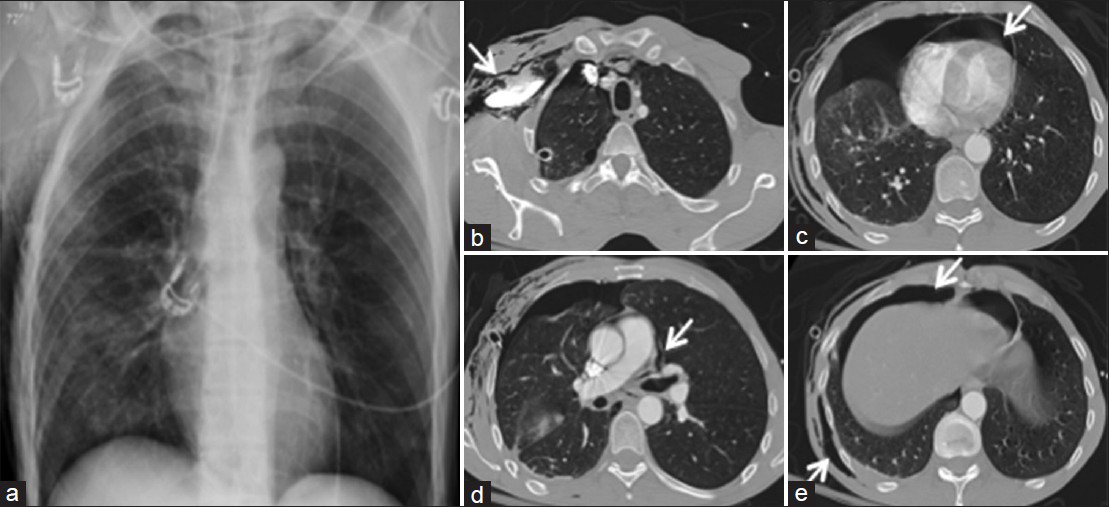

Cardiac and pericardial injuries may be identified via evaluation of direct or indirect signs [Table 1]. Sternal fractures, acute pectus deformity, underlying mediastinal hematoma, or direct mass effect on the cardiac chambers may be suggestive of cardiac injury [Figure 1].

- 22-year-old male with history of a fall from six stories. (a) Contrast enhanced MDCT images of the chest on sagittal view demonstrates a minimally displaced distal sternal fracture (arrow). (b) Sagittal and (c-d) axial views demonstrate an associated mediastinal hematoma (arrows). (e and f) Axial lung windows show bilateral pulmonary contusions/lacerations and small pneumothoraces (arrows). Sternal fractures and mediastinal hematomas are associated with cardiac injury. Patients may benefit from echocardiography and cardiac monitoring including serial ECGs and troponins with a low threshold for repeat imaging.

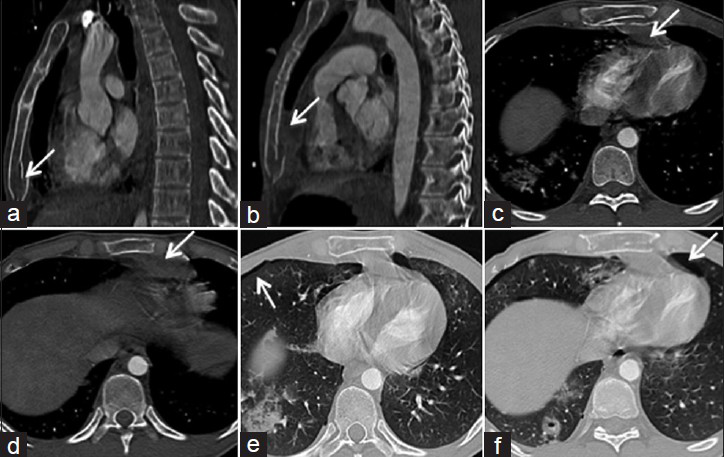

Hemopericardium and pneumopericardium are direct signs of a cardiac or pericardial injury. In the setting of trauma, pericardial effusions are usually presumed to be hemopericardium related to cardiac or pericardial injury until proven otherwise [Figures 2 and 3].[5] Pneumopericardium may be difficult to differentiate from pneumomediastinum or medial pneumothorax on plain films alone. MDCT more sensitively detects air in the pleural cavity, mediastinum, and pericardium [Figure 4].

- 17-year-old male with a stab wound to the left chest. Contrast-enhanced MDCT demonstrates locules of air in the anterior chest wall (arrow), a small amount of hemopericardium (asterisk), and high density (>70 HU) left pleural effusion. Indirect findings of cardiac injury suggest an increased risk of cardiac or pericardial injury.

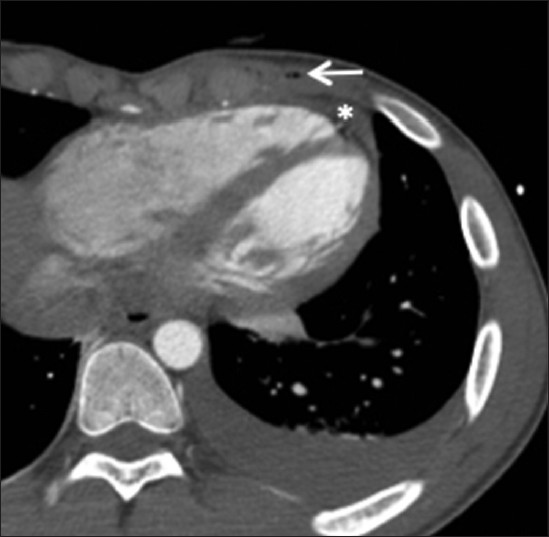

- 83-year-old female with blunt trauma including imaging findings of bilateral rib fractures, lung contusions and lacerations on (a) plain film. (b and c) Contrast enhanced MDCT axial thoracic images demonstrate hemopericardium (arrows), (d) rib fractures (arrows), and (e) traumatic pectus deformity (arrow).

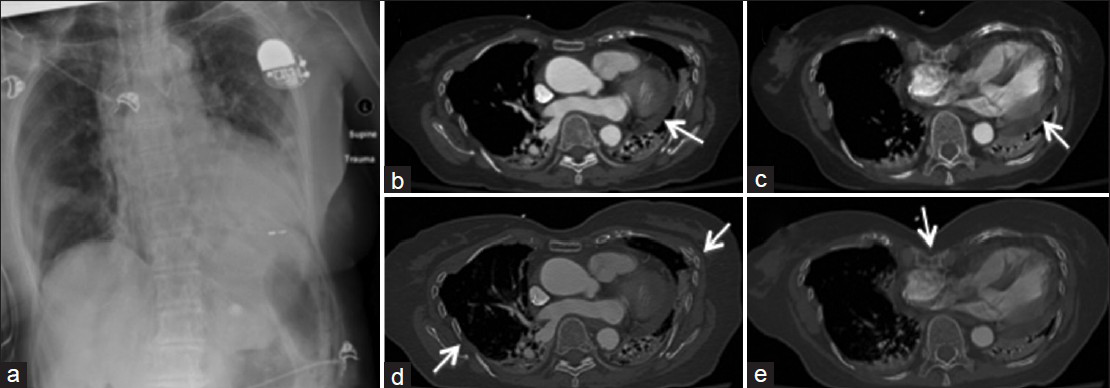

- 48-year-old male trauma patient with multiple thoracic injuries including right subcutaneous emphysema, bilateral pulmonary contusions, pneumothorax, rib fractures, and pneumopericardium, suspected on the (a) supine radiograph. (b-e) Contrast-enhanced MDCT axial images of the chest confirm pneumopericardium (arrow in c), pneumomediastinum (arrow in d), and right pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema (arrows in e).

Pericardial tears in a trauma patient may lead to cardiac herniation. Findings of pericardial tear on MDCT include cardiac axis deviation, focal pericardial discontinuity, “collar” sign of the herniated heart, or empty pericardial sac sign (air in the empty pleuropericardium due to cardiac dislocation into the hemithorax).[1]

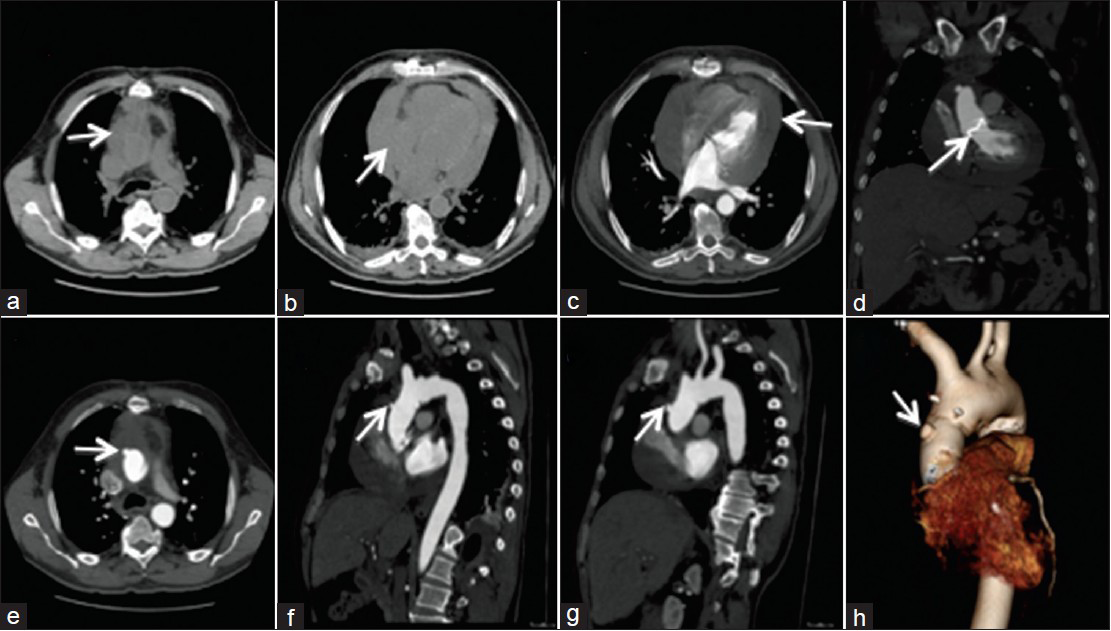

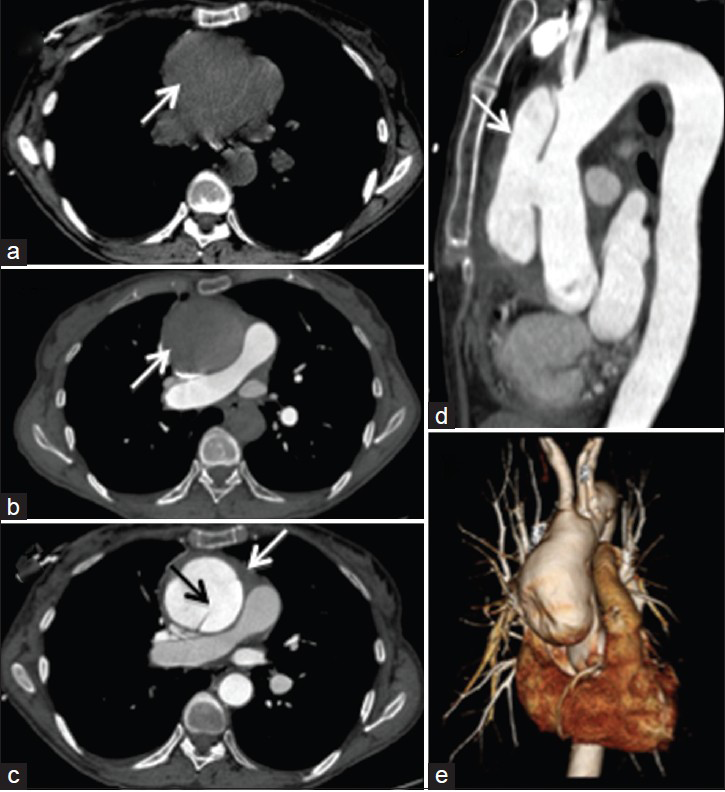

Rapid accumulation of pericardial fluid can lead to cardiac tamponade, limiting the cardiac inflow and reducing the stroke volume.[6] Hemorrhagic pericardial fluid and distended central veins (inferior vena cava, superior vena cava, hepatic veins) with or without evidence of contrast reflux and periportal edema are CT features that suggest cardiac tamponade. Indirect signs of cardiac tamponade include a compressive deformity of cardiac chambers, especially the more compliant right-sided chambers [Figure 5]. The anterior surface of the heart is flattened with a reduction in the anteroposterior (AP) diameter, described as the “flattened heart sign.”[7] Right atrial pseudoaneurysm has been recently described in the literature as a rare manifestation of blunt injury to the chest.[8]

- 64-year-old male trauma patient. (a-c) Contrast enhanced MDCT axial images of the chest show a large hyperdense pericardial effusion (arrow in a and c) causing mass effect and flattening of the right atrium (arrow in b) suggestive of cardiac tamponade. (d) Coronal view demonstrates aortic valve (arrow) and ascending aorta replacement using the modified Bentall technique. (e) Axial, (f, g) sagittal and (h) 3D-reformat demonstrate outpouching (arrows) at the origin of the aorta is not a pseudo-aneurysm, but is rather an over-sewn side arm remnant with hyper-dense bio-glue around the graft (e-h).

AORTIC AND OTHER VASCULAR INJURIES

Major causes of traumatic aortic injury include high-speed motor vehicle collisions, falls from a height, pedestrian–automobile collisions, and crush injuries.[9] The morbidity and mortality from aortic injury is high and is immediately lethal in 80–90% of cases.[9] Aortic and vascular injury has been postulated to be a result of various potential mechanisms including rapid deceleration, shearing forces, and increased intravascular pressure caused by compression or the “osseous pinch” representing aortic compression between the anterior chest wall and the thoracic spine.[9] The most common site of aortic injury is at the aortic isthmus, followed by the ascending aorta, the descending aorta, and the aortic arch.[9] MPRs in different planes and three-dimensional volume-rendered images may improve the visualization of traumatic aortic injuries, and may be helpful to the vascular surgeon or interventional radiologist for planning treatment.

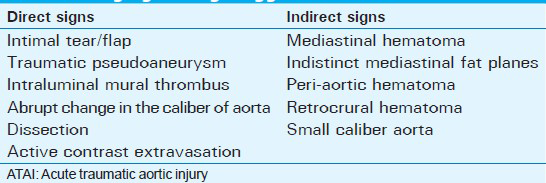

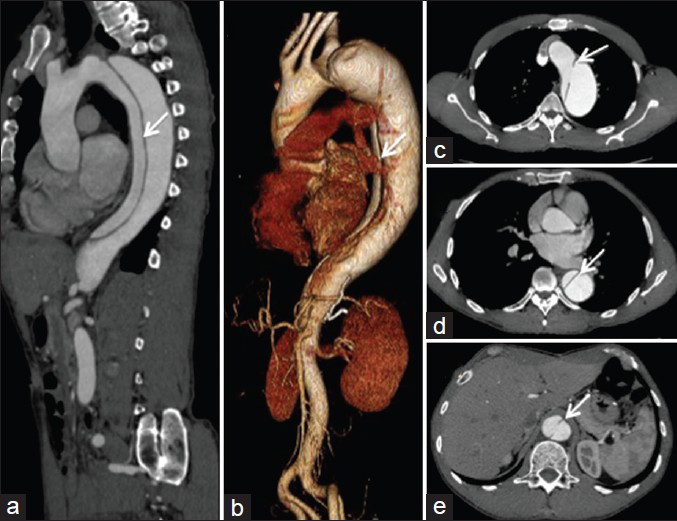

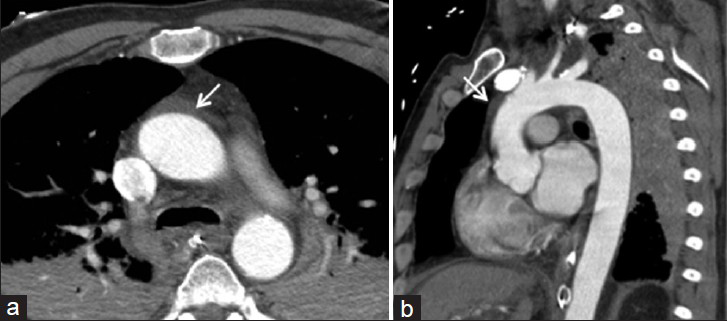

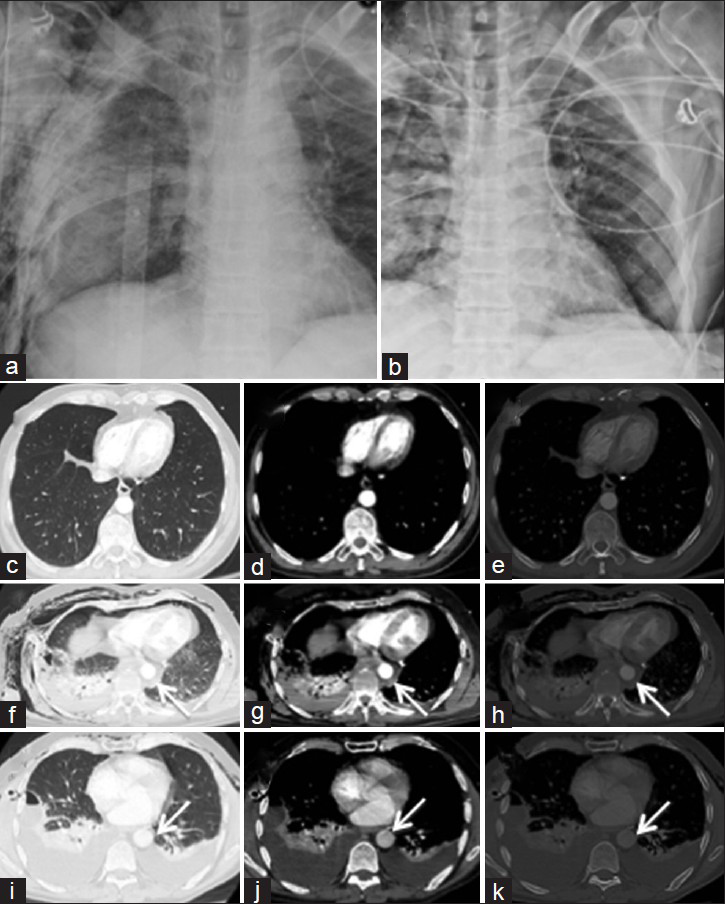

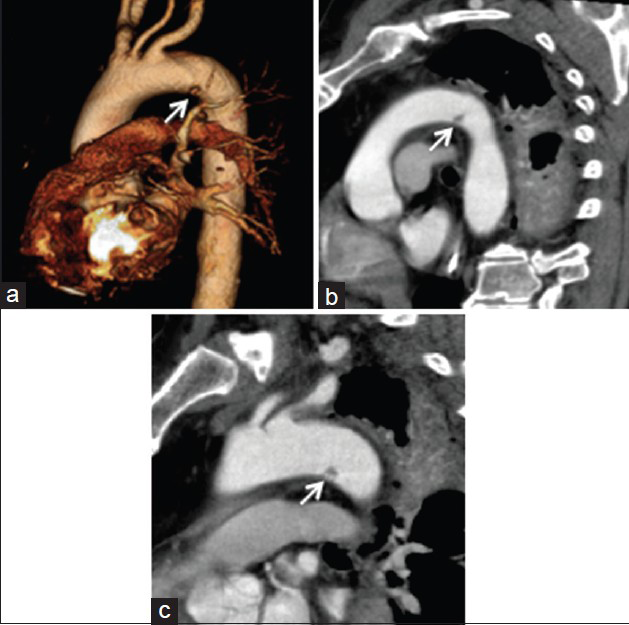

Imaging findings in acute traumatic aortic injuries have been classified as direct and indirect signs [Table 2]. Direct signs of traumatic aortic injury include pseudoaneurysm [Figure 6], intimal tear/flap or dissection [Figures 7 and 8], intraluminal mural thrombus [Figure 9], abrupt change in the caliber of aorta (pseudocoarctation), or active contrast extravasation.[10] Indirect signs may consist of mediastinal hematoma, indistinct mediastinal fat planes, peri-aortic hematoma [Figures 10 and 11], retrocrural hematoma, or a small caliber aorta. Mediastinal hematoma is a non-specific finding that can be associated with mediastinal venous injuries, in which case the fat plane between the hematoma and aorta is typically maintained.[9]

- 17-year-old male trauma patient. (a) Contrast enhanced sagittal MDCT image of the chest and (b and c) 3D volume-rendered technique reconstructions demonstrate a traumatic aortic injury with pseudoaneurysm (arrows) along the inferomedial wall of the aortic isthmus, 1 cm distal to the left subclavian artery origin. (d) Axial lung window reveals other injuries including right pneumothorax with bilateral pulmonary contusions and dependent consolidation bilaterally. (e) Axial soft tissue window indicate loss of fat plane around esophagus (arrow) likely due to mediastinal hematoma, although esophageal injury cannot be excluded. (f) Plain film shows an intravascular stent (arrow) was subsequently placed endoscopically.

- 70-year-old female with chest pain. (a) Unenhanced and (b) enhanced axial MDCT images of the chest to exclude pulmonary embolus demonstrate a dilated ascending aorta with suspected dual lumen (white arrows). (c) Repeat non-gated study in the arterial phase demonstrates a Stanford A aortic dissection with intimal flap (black arrow), dilated ascending aorta, and small hemopericardium (white arrow). (d) Sagittal oblique multi-planar reconstruction and (e) 3D volume rendering technique images show age indeterminate aortic dissection (white arrow) and dilated aortic root.

- 60-year-old male with a descending aortic dissection. (a) Contrast-enhanced MDCT of the chest and abdomen in sagittal plane demonstrates intimal flap (white arrows), beginning immediately distal to the left subclavian artery and ending just above the renal arteries. (b) 3D volume rendered technique and (c-e) enhanced axial MDCT images confirm the finding of intimal flap. Axial images are important in evaluating the branch vessels including the celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), inferior mesenteric artery (IMA), and renal arteries to ensure that blood supply is preserved (being supplied from the true lumen) to minimize the risk of end-organ infarction.

- 43-year-old male with intraluminal mural thrombus. (a and b) Axial contrast-enhanced MDCT images, as well as (c) sagittal, and (d) coronal views demonstrate a thoracic vertebral hyperextension fracture (arrows). (e) Axial and (g) sagittal oblique images show hyperextension within the descending aorta, there is an area of wall thickening associated with a focal intraluminal hypo-density (arrows), suggestive of acute aortic injury. Follow-up (f) axial and (g and h) sagittal oblique images show the intraluminal thrombus and associated vessel wall thickening resolved, compatible with minimal aortic injury. Spinal column injuries, particularly flexion-distraction or chance-type fractures, indicate high-impact trauma and can be associated with aortic injury.

- 49-year-old male trauma patient. (a) Axial and (b) sagittal contrast enhanced MDCT images of the chest show peri-aortic hyper-density (arrows) and stranding compatible with peri-aortic hematoma. No luminal irregularity noted; peri-aortic hematoma/stranding is likely secondary to venous injury. Lung findings include bilateral dependent consolidation.

- 51-year-old male cyclist struck by a car. (a and b) Supine radiographs of the chest demonstrate extensive thoracic injuries including bilateral rib fractures and pneumothoraces, as well as pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema. (c-e) Axial contrast-enhanced MDCT images from 2 years before demonstrate normal AP diameter of the aorta compared with trauma CT and 2-day post-trauma follow-up CT. (f–h) Images from trauma CT demonstrate peri-aortic hematoma surrounding the descending aorta (arrows), in addition to bilateral flail chest, subcutaneous emphysema, right hemo-pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum. No luminal irregularity involving the descending aorta was noted. (i–k) Follow-up CT imaging two days later demonstrates resolution of the hematoma.

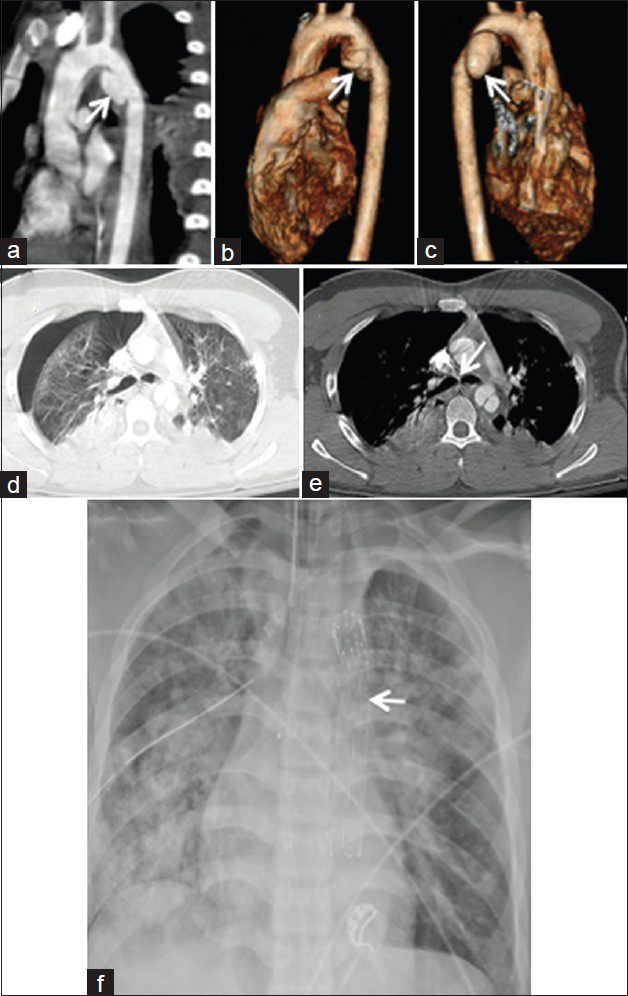

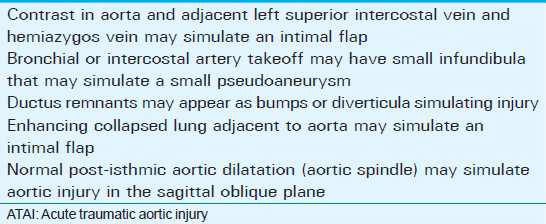

Minimal aortic injury usually involves the intima and accounts for 10% of patients with traumatic aortic injury [Figures 9 and 12].[9] Mimickers of traumatic aortic injury on MDCT may be either anatomic or technical and are reviewed elsewhere [Table 3].[9]

- 59-year-old male trauma patient with intraluminal thrombus. (a-c) Arterial phase sagittal contrast-enhanced MDCT images through the chest show minimal aortic injury (arrows) at the site of the ligamentum arteriosum. The natural history of minimal aortic injuries has not been clarified; however, institutional experience suggests that these tend to heal in the short term, although long-term sequelae are not known.

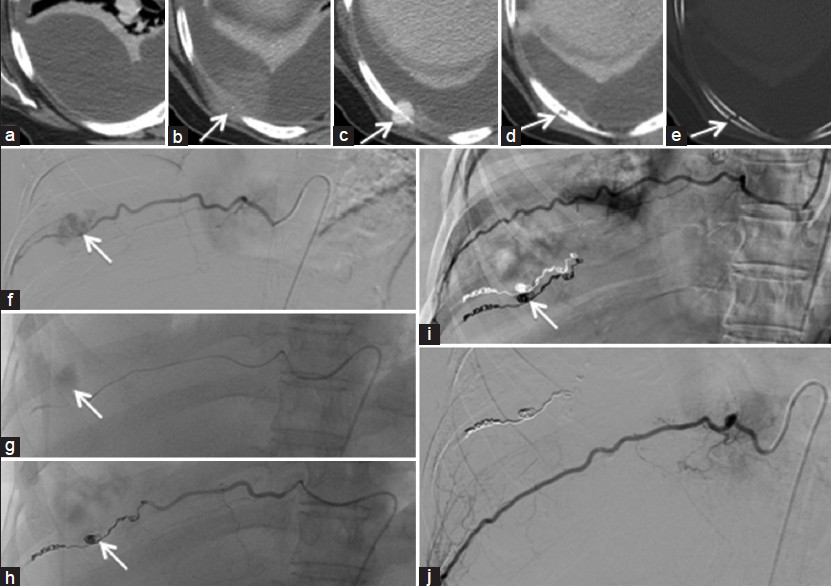

INTERVENTION

Traditionally, traumatic aortic injuries were repaired via an open approach. However, the majority of aortic injuries can now be treated with stent grafts. Meta-analyses have shown a decrease in postoperative mortality, ischemic spinal cord complications, and stroke.[11] The endovascular approach is minimally invasive and patients do not require systemic heparinization, which is particularly important because the patients often have multiple other significant injuries.[11] MDCT is also useful for planning endovascular procedures [Figure 13].

- 53-year-old female breast cancer patient who had a fall down the stairs. (a-e) Contrast enhanced MDCT axial images of the chest focussed on the right lower hemithorax show a loculated right pleural fluid collection with high density compatible with haemorrhage. A localized area of hyper-density represents sentinel clot (arrows in b and c) at the site of underlying rib fracture (arrows in d and e). (f-j) Static digital subtraction angiography (DSA) images show a traumatic right-sided intercostal artery pseudo-aneurysm (arrows in f and g) with successful trans-arterial embolization using a coil (arrows in h and i).

CONCLUSION

MDCT plays a key role in identifying and directing the management of CV injuries in major trauma patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

NS is supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR FRN 120988) and the Radiology Society of North America Research and Education Foundation (#RR1561). AZ is supported by the Radiology Society of North Research and Education Foundation Scholar Grant (RSCH1329).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2015/5/1/48/163992

REFERENCES

- Blunt cardiac rupture. The Emanuel Trauma Center experience. Arch Surg. 1995;130:852-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of acute thoracic injury: The advent of MDCT screening. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26:305-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of imaging in penetrating and blunt traumatic injury to the heart. Radiographics. 2011;31:E101-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pictorial review: Computed tomography features of cardiovascular emergencies and associated imminent decompensation. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18:127-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tension pericardial collections: Sign of ‘flattened heart’ in CT. Eur J Radiol. 1996;23:250-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute traumatic aortic injury: Imaging evaluation and management. Radiology. 2008;248:748-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute aortic syndrome and blunt traumatic aortic injury: Pictorial review of MDCT imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:24-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced mortality, paraplegia, and stroke with stent graft repair of blunt aortic transections: A modern meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47:671-5.

- [Google Scholar]