Translate this page into:

Unexpected Angiography Findings and Effects on Management

Address for correspondence: Dr. Amy R Deipolyi, Interventional Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065, USA. E-mail: deipolya@mskcc.org

-

Received: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Despite progress in noninvasive imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, conventional angiography still contributes to the diagnostic workup of oncologic and other diseases. Arteriography can reveal tumors not evident on cross-sectional imaging, in addition to defining aberrant or unexpected arterial supply to targeted lesions. This additional and potentially unanticipated information can alter management decisions during interventional procedures.

Keywords

Angiography

computed tomography

embolization

interventional oncology

magnetic resonance imaging

[SHOW_RELATED_PUBMED_ARTICLES]

INTRODUCTION

Cross-sectional imaging strongly influences the diagnosis and management of several pathologic entities including liver lesions, pulmonary nodules, and gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage. Often, patients will have pre procedure cross-sectional imaging that guides the management plan. While high-quality computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offer excellent sensitivity and specificity for detecting lesions and characterizing vascular anatomy, accuracy depends on the quality of images obtained, and the accuracy with which they are interpreted. Conventional angiography can provide additional diagnostic and anatomic vascular information that may not have been apparent on pre procedure imaging. Characteristic angiography findings of liver lesions include vascular proliferation, tumor staining, mass effect, and arteriovenous shunting; the distribution and magnitude of vascular changes can aid in diagnosis and prognosis.[1] Conventional angiography also serves to define the vascular anatomy, evaluate the extent of disease, and help assess the viability of surgical resection in candidates.[2]

Unexpected angiographic findings prompt the Interventionalist to alter or abort the management plan during the procedure. Examples of possible unexpected findings include previously undetected lesions, unanticipated or aberrant vascular supply to lesions, and additional diagnostic information. In these situations, the interventionalist may have to expand the region of embolization, alter the approach, perform additional procedures at a later date, attempt alternative routes or abort the procedure, and change the management plan to surgical or medical treatment modalities.

PREVIOUSLY UNDETECTED LESIONS: LIVER-DIRECTED THERAPY

Liver-directed therapy with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radioembolization (TARE) is a mainstay of primary and secondary liver cancer treatment. Pre procedure imaging with CT and MRI is standard and aids in the detection of tumors and in planning for transarterial intervention.

The reported sensitivity and specificity of CT and MRI for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are 80–100% and 90–95%, respectively, when including all sizes of tumors but decrease significantly for tumors 1–2 cm and decrease even further for tumors <1 cm.[3] In the evaluation of liver metastases, cross-sectional imaging has been shown to be 90–100% sensitive when including all sizes of tumors, but this again decreases significantly for tumors <1 cm.[4]

Despite reported accuracy of cross-sectional imaging, unanticipated tumors are frequently encountered during arteriography preceding therapy [Figures 1–3]. Not only this information is diagnostic and useful in altering the therapeutic plan by detecting additional lesions, but also it aids in prognostication.

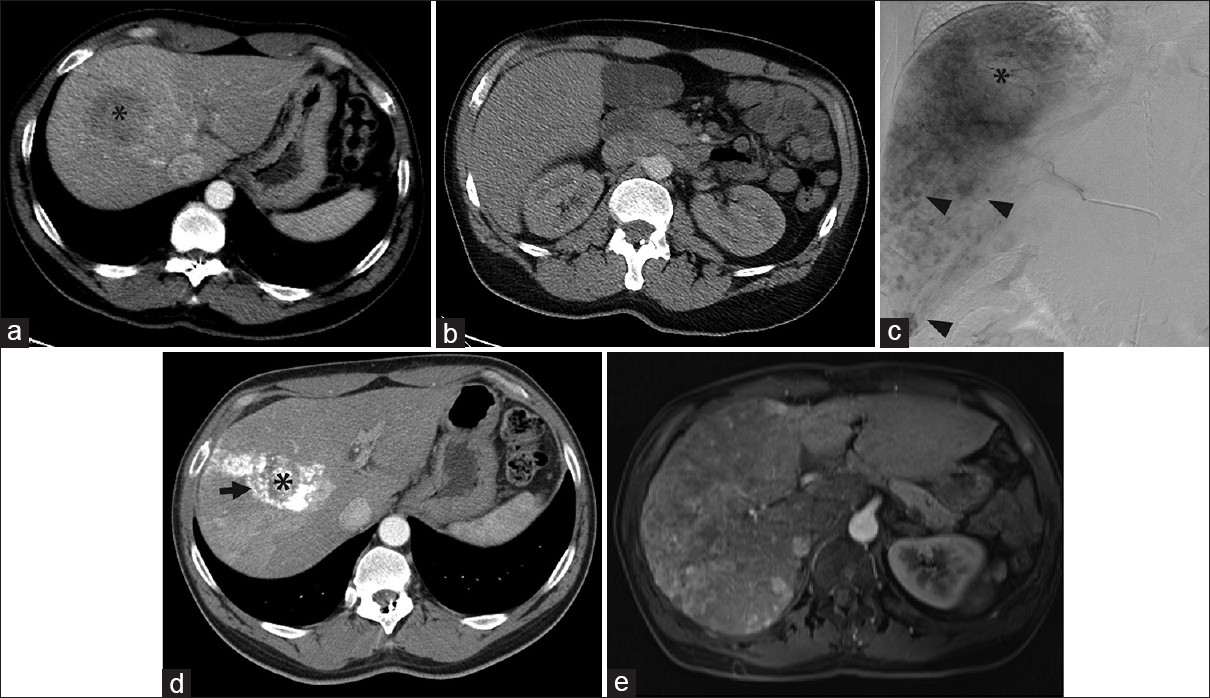

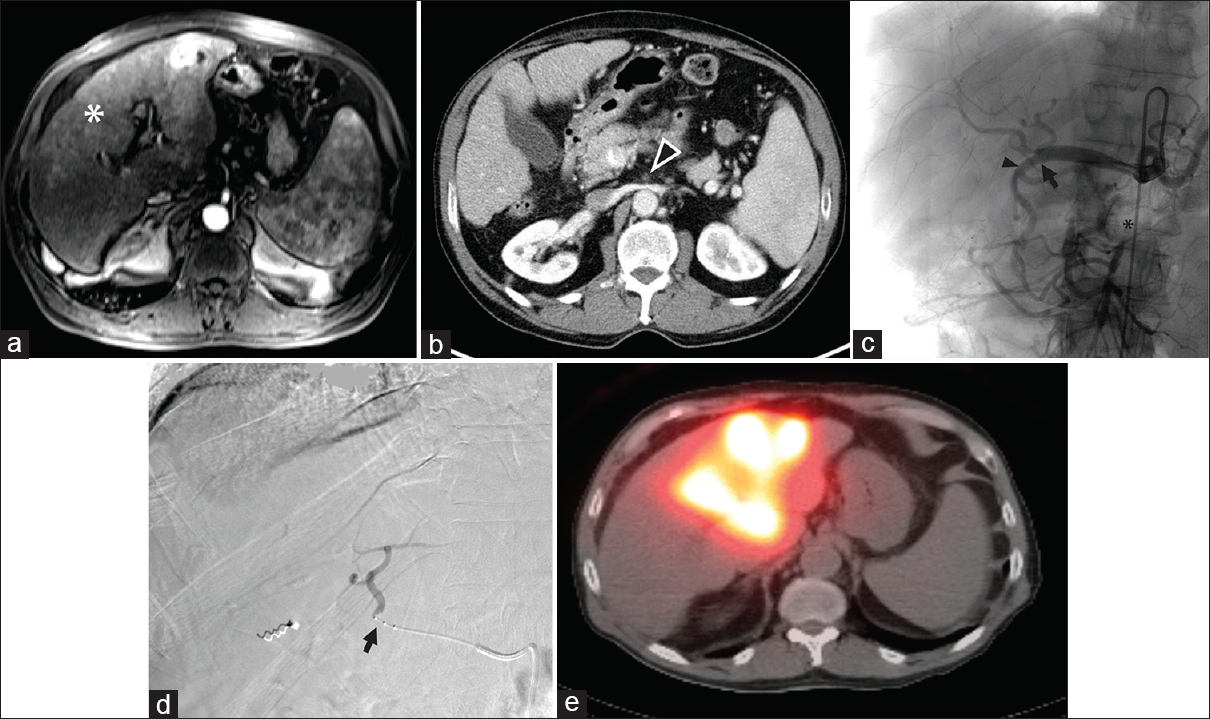

- Angiographic findings contradictory to those on computed tomography. (a) Computed tomography demonstrated a 5.1-cm right liver mass, presumed hepatocellular carcinoma (black asterisk) in a 55-year-old male with hepatitis B virus cirrhosis. (b) No tumors were identified on computed tomography in the inferior right hepatic lobe. The original plan was for selective transarterial chemoembolization. (c) Angiography performed within 1 month of the computed tomography revealed a great number of small amorphous hypervascular nodules scattered in the inferior half of the right liver (black arrowheads). Only the dominant 5.1-cm right liver mass (black asterisk) was treated with transarterial chemoembolization. (d) Computed tomography 4 weeks later showed no tumors beyond the lipiodol-staining (arrow) of the dominant, embolized tumor (black asterisk). (e) However, magnetic resonance imaging 1 year later showed extensive multifocal and infiltrative hepatocellular carcinoma in the right liver with osseous metastases. No further liver therapy was performed, and the bone metastases (not shown) were treated with palliative radiation therapy.

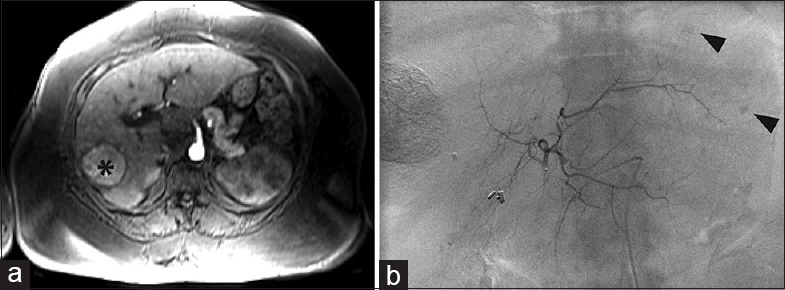

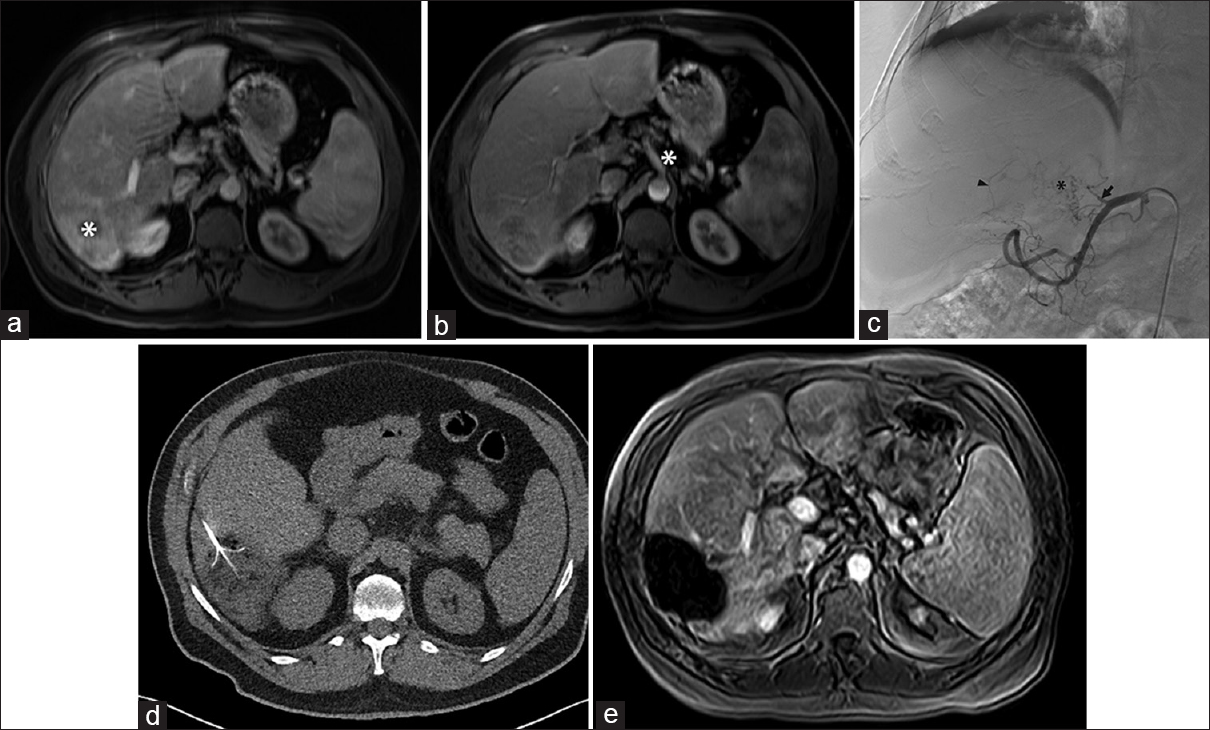

- Additional lesions requiring additional treatment session. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging of a 59-year-old female with hepatitis C virus cirrhosis demonstrated a 5 cm hepatocellular carcinoma in liver segment 5 (black asterisk) with possible satellite nodules. The original plan was selective transarterial chemoembolization of the 5 cm mass. (b) Left hepatic angiography within 2 weeks of the magnetic resonance imaging showed two subcentimeter hypervascular nodules in segment 2 (black arrowheads) and a hypervascular focus in segment 7/8 that required a second transarterial chemoembolization procedure.

- (a) Magnetic resonance imaging of a 62-year-old female with hepatitis B virus disease and prior transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma in segments 4A and 7 showed no new tumors and an embolization cavity (white asterisk) without evidence of residual disease. However, rising alpha-fetoprotein prompted angiographic evaluation. (b) On angiography performed within 1 month of the magnetic resonance imaging, abnormal hypervascularity was identified near hepatic dome, in the region of the previously treated segment 7 tumor, supplied by subsegmental hepatic arterial branches and right inferior phrenic artery (black arrow) branches. Transarterial chemoembolization was performed via these branches. Two months following transarterial chemoembolization, alpha-fetoprotein returned to normal.

UNANTICIPATED VASCULAR SUPPLY TO TARGET LESIONS

Liver tumors, especially HCC, rely heavily on angiogenesis for growth and survival. The ability of such tumors to develops new, abnormal vascular supply may confound efforts to treat them. Aberrant vascular supply can be from extrahepatic vessels such as the inferior phrenic artery or intercostal arteries[5] and branches of the internal mammary artery [Figure 4]. It is important to recognize these other sources when performing TACE/TARE.

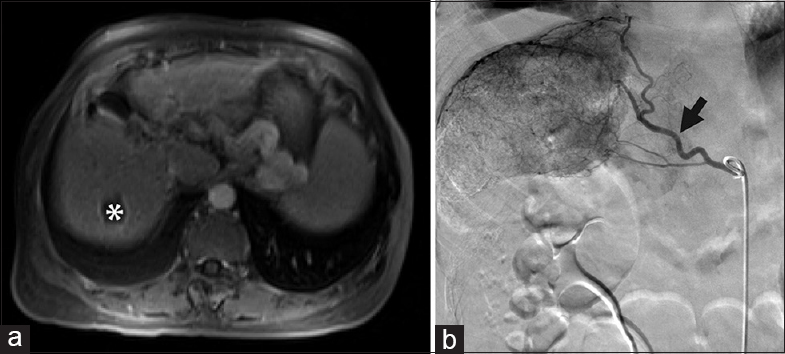

- Recruitment of inferior phrenic artery and branch of the dorsal pancreatic artery. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging showed a new segment eight hepatocellular carcinoma (arrowhead) in a 70-year-old male with a history of chronic hepatitis B virus cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma and prior transarterial chemoembolization and ablation procedures. The plan was transarterial radioembolization to the lesion. (b) Angiography revealed much more extensive disease than seen on magnetic resonance imaging showing that the arterial supply arose not only from the right hepatic branches but also a variant right lateral branch of the dorsal pancreatic artery (black arrowhead) arising from the common hepatic artery, branches of the gastroduodenal artery (black arrow) and (c) the right inferior phrenic artery (black arrow) with shunting to the pulmonary circulation. (d) During yttrium-90 mapping, embolization of the right inferior phrenic, gastroduodenal, and right gastric artery was performed, to allow for redistribution solely via the right hepatic where transarterial radioembolization was then performed. (e) Magnetic resonance imaging 3 months later showed no residual disease.

In certain cases, tumors may not have a vascular supply conducive to intra-arterial therapy [Figures 5 and 6]. This can be due to several factors: multiple prior TACE procedures that disrupt the vascular supply in such a way that a vascular approach is unfeasible; inability to traverse stenosis or occlusion of the main vascular supply; or vasculature distribution that involves other organ systems such as the bowel. In these cases, alternative approaches are considered including percutaneous and intraoperative ablation.

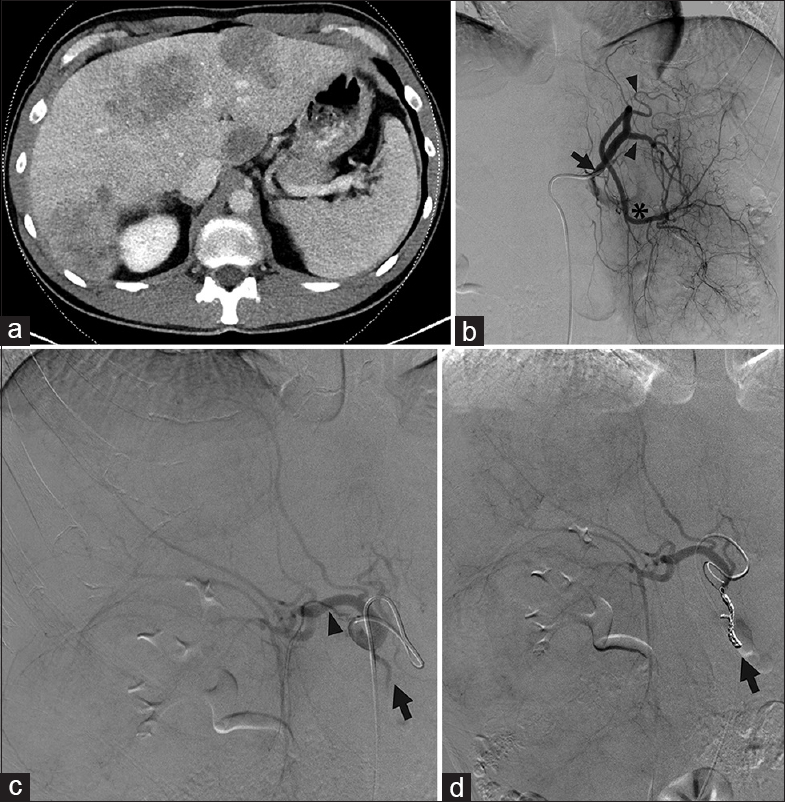

- Superior mesenteric artery occlusion precluding gastroduodenal artery embolization during transarterial radioembolization. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging showed multifocal bilobar hepatocellular carcinoma (white asterisk) in a 71-year-old male. (b) Superior mesenteric artery occlusion (arrowhead) was also noted on computed tomography. (c) Angiography demonstrated that the bowel was supplied by the celiac artery via the gastroduodenal artery, via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade, precluding gastroduodenal artery embolization. However, the right and left hepatic arteries and gastroduodenal artery originated from the common hepatic artery in a trifurcation (black arrow), raising concern for nontarget embolization to the bowel from yttrium-90 embolization of either hepatic artery since the gastroduodenal artery (black arrowhead) supplied the superior mesenteric artery distribution due to superior mesenteric artery occlusion (black asterisk). (d) Therefore, a Surefire catheter (Surefire Medical Inc., Westminster, CO, USA; black arrow) was used to prevent retrograde flow of the yttrium-90 embolic agent during embolization. (e) Single-photon emission computed tomography imaging showed delivery to the liver parenchyma without activity in the bowel.

- Transarterial therapy, not possible. (a) Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated hepatocellular carcinoma (white asterisk) in a 59-year-old male with a transplanted liver, performed 17 years earlier, for hepatitis C virus cirrhosis. (b) Celiac axis (white asterisk) appeared widely patent, and the original plan was for transarterial radioembolization. (c) However, angiography demonstrated chronic obstruction of the proper hepatic artery (arrow) precluding transarterial therapy that had not been appreciated on the pre procedure magnetic resonance imaging. The liver was supplied by extensive but fine collateral vessels from the left gastric and gastroduodenal artery branches (black arrowhead), as well as branches (black asterisk) from the remaining proper hepatic arterial stump (black arrow). (d) The patient later underwent RFA of the tumor. (e) Magnetic resonance imaging 4 weeks later showed no residual disease.

ABERRANT VASCULAR ANATOMY

Arterial and venous anatomy is variable among individuals. Variation in origin, number, and course of arteries and veins is common. It is important to identify anatomic variation as it may alter the treatment plan. For liver-directed therapy, replaced and accessory hepatic arteries will alter treatment strategies [Figure 7].

- Replaced right hepatic artery. (a) Computed tomography showed tumors in both hepatic lobes in a 49-year-old male with metastatic colon cancer. Arterial phase images were not obtained. The pre procedure treatment plan was for transarterial radioembolization. (b) During mapping, angiography showed a left gastrohepatic trunk (black arrow) with multiple gastric branches (black arrowheads) arising before the left hepatic artery (black asterisk). There are a marked enlargement and inferior deviation of the left hepatic lobe due to large masses. (c) A replaced right hepatic artery (black arrowhead) from the superior mesenteric artery was not appreciated on pre procedure imaging but identified angiographically. The gastroduodenal artery (black arrow) originated from the right hepatic artery (black arrowhead). (d) The gastroduodenal artery was coil embolized (black arrow). Yttrium-90 mapping of the left and right lobes was therefore performed by macroaggregated albumin infusion via two separate catheter placements.

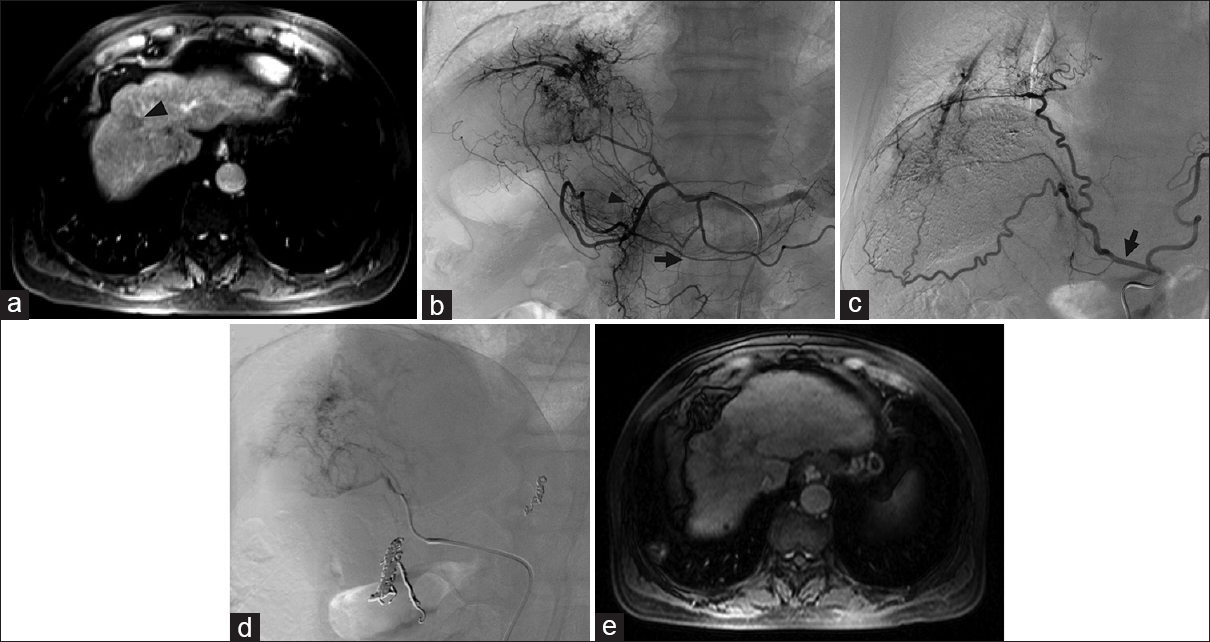

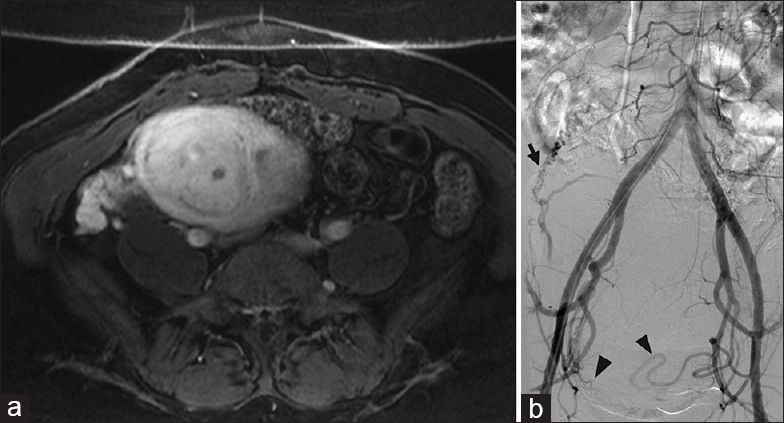

For uterine fibroid embolization, the ovarian artery can often supply the fibroid(s), especially in patients with large fundal fibroids, tubo-ovarian pathology, or prior pelvic surgery [Figure 8].[6] At times, the supply may not be visible until after the embolization is performed, with a resultant change in flow dynamics and redistribution of flow to the ovarian artery.[6]

- Ovarian artery supply to the uterus. (a) Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates a fibroid uterus in a 48-year-old female with pelvic pain and menorrhagia. (b) Abdominopelvic aortogram demonstrates supply to the enlarged fibroid uterus from branches from the right and left uterine arteries (black arrowheads). In addition, the enlarged right ovarian artery (black arrow) supplies a portion of the superior uterus. All three vessels were embolized with particles, to assure clinical response.

ADDED DIAGNOSTIC INFORMATION FROM ANGIOGRAPHY

While CT and MRI are helpful in differential diagnostic considerations, angiography provides dynamic information that, by showing the evolution of blood flow over time, can help to sort through the differential diagnosis.

CT and MRI are helpful in the diagnosis of hepatic tumors, and in differentiating among the diagnostic considerations. Angiography provides dynamic information that, by showing the propagation of blood flow over time, can help to sort through the differential diagnosis. In the liver, arterioportal and arteriovenous shunts can be revealed that are only suggested or not demonstrated on cross-sectional imaging. Such shunting can suggest particular tumors such as HCC or certain metastases. From a procedural standpoint, arteriovenous shunting influences the dose of radioembolization therapy can be delivered. Arteriovenous shunting is also associated with poor prognosis.[7]

In the lung, parenchymal lesions on CT tend to enhance, without focal detail in regard to vascular anatomy. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), the majority associated with Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome, often displays tortuous feeding arteries, aneurysms, and dilated draining veins which may be seen on CT. However, other pulmonary arterial or venous diseases such as pseudoaneurysms and mass lesions can be difficult to distinguish at times [Figures 9 and 10]. Sensitivity and specificity of CT for detecting AVMs are 83% and 78% for the whole lung and 72% and 93% for lobar evaluations, respectively, whereas pulmonary arteriography has a sensitivity and specificity of 70% and 100% for the whole lung and 68% and 100% for lobar evaluation, respectively.[8] Beyond providing higher specificity, transcatheter pulmonary arteriography allows for simultaneous diagnosis and management.

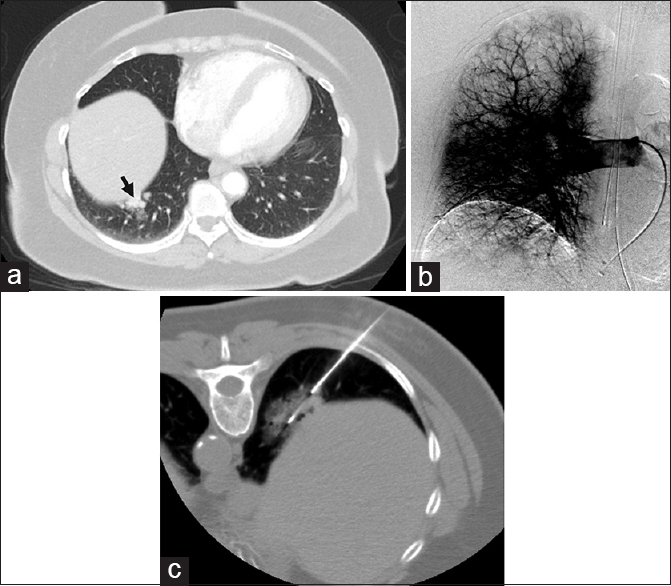

- Pulmonary angiography excludes arteriovenous malformation. (a) A 64-year-old female with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was found to have hypervascular right lower lobe lung nodules, with imaging features suggestive of arteriovenous malformations (black arrow). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography findings were considered suspicious enough to warrant a conventional angiogram and possible embolization. (b) Right pulmonary angiography demonstrated no evidence of dilated artery or early draining vein, excluding arteriovenous malformations. (c) Computed tomography-guided biopsy of a dominant nodule was then performed and revealed a diagnosis of nonsmall cell carcinoma.

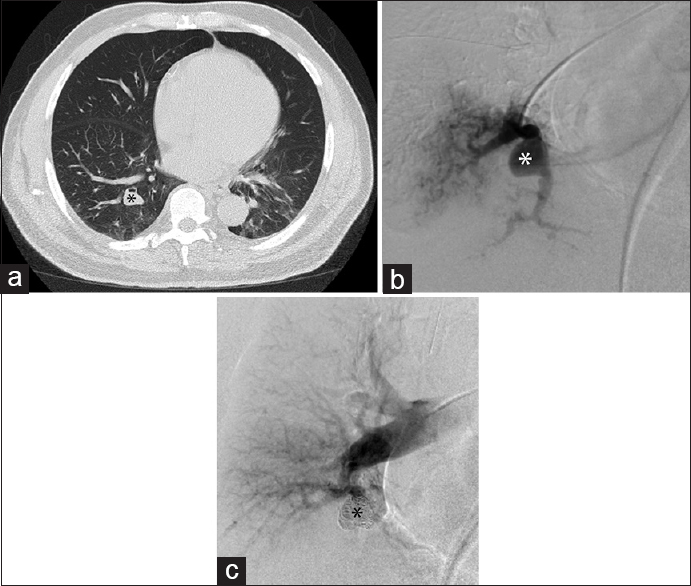

- Pulmonary angiography excludes arteriovenous malformation and diagnoses pseudoaneurysm. (a) Chest computed tomography in a 70-year-old male demonstrates a right lower lobe pulmonary nodule (black asterisk) thought to represent an arteriovenous malformation. Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram was not performed, as the findings were considered suspicious enough to warrant conventional angiography. (b) Right lower lobe segmental pulmonary arteriogram demonstrated a pseudoaneurysm (white asterisk) of the vessel perfusing the medial portion of the base of the right lower lobe, without a draining vein to suggest an arteriovenous malformation. (c) Coil embolization (black asterisk) of the pseudoaneurysm was performed.

Conventional angiography remains the modality of choice to demonstrate subtle vascular lesions. For GI bleeds, endoscopic evaluation is generally performed first. However, if endoscopy is unable to identify the source of bleeding, either because no bleeding is found or excess bleeding prevents localization, angiography can play diagnostic and therapeutic roles. The location of active GI bleeding is identified by extravasation of contrast into the bowel lumen and can be seen at bleeding rates as low as 0.5 mL/h. Angiodysplasias, virtually invisible by axial computerized imaging, can be identified by the tortuous network of vessels and dilated, rapidly draining vein (s). Vasculopathies, such as fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD) and segmental arterial mediolysis (SAM), can be identified as well. FMD, most commonly affecting the renal and cerebral arteries, but occasionally the mesenteric vessels, has three major subtypes affecting different layers of the arterial wall; the most common type, which involves the medial layer, gives a classic “string-of-beads” sign with alternating dilations and stenosis.[9] SAM, classically affecting the splanchnic vessels, is due to the lysis of the outer media of the arteries and characterized by segmental, scattered aneurysms, stenosis, and occlusions with the main distinguishing feature being the high prevalence of dissecting aneurysms [Figure 11].[10] SAM and FMD have some overlapping histological and radiographic appearances and may be a spectrum of one disease.

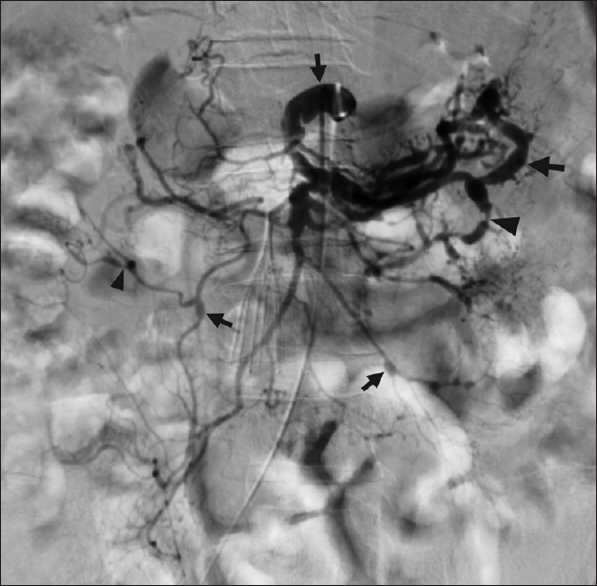

- Mesenteric arteriography diagnoses segmental arterial mediolysis. A 62 year old man with spinal cord compression from a thoracic tumor developed massive hemorrhage following surgical decompression. The patient required numerous transfusions and aggressive vasopressor support. He subsequently developed massive melena, the source of which was unclear on endoscopy. Celiac and superior mesenteric arteriography unexpectedly demonstrated scattered stenoses (black arrowheads), aneurysms (black arrows), and arterial dissections, in a pattern consistent with segmental arterial mediolysis. The procedure was stopped, as it was now recognized that the patient was not amenable to endovascular intervention.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2016/6/1/33/189727

REFERENCES

- Angiography of primary liver cancer. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1971;113:70-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatocellular carcinoma: Clinical and angiographic findings and predictability for surgical resection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1979;132:7-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging techniques for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:697-711.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of colorectal liver metastases. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:25-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extrahepatic blood supply to hepatocellular carcinoma: Angiographic demonstration and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:39-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Uterine fibroid vascularization and clinical relevance to uterine fibroid embolization. Radiographics. 2005;25(Suppl 1):S99-117.

- [Google Scholar]

- High lung shunt fraction in colorectal liver tumors is associated with distant metastasis and decreased survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1604-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Digital subtraction pulmonary arteriography versus multidetector CT in the detection of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1582-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fibromuscular dysplasia: What the radiologist should know: A pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2015;6:295-307.

- [Google Scholar]