Translate this page into:

Multiple organ tuberculomas in infant

*Corresponding author: Sri Asriyani, Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Hasanuddin University, Makassar, Indonesia sri_asriyani@med.unhas.ac.id

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Asriyani S, Syahril E, Nelly. Multiple organ tuberculomas in infant. J Clin Imaging Sci 2022;12:30.

Abstract

Tuberculoma is a space-occupying lesion resulting from the containment of the inflammatory process in metastatic tuberculosis, which most commonly occur in the brain and lungs. This form of tuberculosis is commonly found in adults, but rarely seen in children. Here we reported a case of an infant with multiple organ tuberculomas. The patient had unspecific signs and symptoms. There were also multiple cervical lymph nodes enlargement and weakness in both lower limbs and right hand. Chest radiograph showed a left pulmonary mass which was further evaluated by thorax CT imaging and revealed pulmonary tuberculoma, mediastinal lymphadenopathies, and pneumonia. Cervical ultrasound showed multiple cervical lymphadenites and brain MRI with contrast showed multiple intracranial tuberculomas with focal meningitis. A microscopic examination from gastric lavage sampling revealed a positive acid-fast bacillus smear and a biopsy of a lump in the neck demonstrated a picture of chronic granulomatous lymphadenitis that supports tuberculosis infection. Through this case, we emphasize the importance of the various appearance of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in infants.

Keywords

Tuberculoma

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Infant

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global health problem which is one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide with millions of morbidities each year. According to WHO, around 10-11% of TB cases occur in children and are considered one of the leading causes of death in children in developing countries. In 2016, there were estimated 1,020,000 TB cases in Indonesia with an incidence of 391 cases per 100,000 population, with 32,612 pediatric cases.[1]

The incidence of pediatric TB is often underestimated due to the misperception that prevention of TB in children can be happened by controlling TB in adults and difficulty in diagnosis. Pediatric TB diagnosis becomes challenging because of unspecific symptoms in children, the inability of children to produce sputum for microscopic examination or culture, low sensitivity of examination tools due to the paucibacillary nature of TB in children.[2] Here we present a case of multiple organ tuberculomas in infants with unspecific symptoms. The purpose of this article is to delineate various appearances of TB imaging in multiple organs and the need for a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosing pediatric TB.

CASE REPORT

A 1-year-7-month-old infant presented with shortness of breath since 1 week before admitted to hospital. The patient had a cough for the past 1 month. Intermittent fever history was found for the last 6 months. There were noticeable lumps in the neck that slowly grows over the past 8 months from the size of a marble to 5 × 3 cm in size, conglomerated and well-bordered. No history of seizure, projectile vomiting, TB contact, nor family history of malignancy. History of full-term vaginal delivery assisted by a midwife, with normal birth weight and complete immunization. There was weakness in both legs and right hand for the past 4 months and a nonenhanced head CT from a previous hospital revealed multiple masses in the pons, right basal ganglia and left thalamus; bilateral temporoparietooccipital vasogenic edema with bilateral coronary suture diastasis (sign of increased intracranial pressure) [Figure 1].

- A 1-year-7-months-old infant with multiple organ tuberculomas who presented with shortness of breath, lumps in the neck and weakness on in both legs and right hand. (A-C) Brain window axial, coronal and sagittal view of nonenhanced head CT showed isodense lesion at pons (black arrow) with peripheral edema. (D-E) There was also another lesion with the same density (white arrow) at right caudate nuclei and (F) left thalamus. (D-F) There was finger-like edema at bilateral parietooccipital lobe (head arrows) with unclear mass density in it and widening of bilateral coronaria suture (not shown).

Laboratory findings showed lower hemoglobin level (6.4 gr/dl), higher white blood count (22.3 × 103/mm), lower albumin (2.7 gr/dl), and lower natrium index (127 mmol/L), while other whole blood cell test and other blood biochemical indexes were within normal ranges. The anteroposterior chest radiograph revealed mass density in the left lung field [Figure 2]. Then chest CT imaging was recommended for further evaluation. In the nonenhanced chest CT, a large pulmonary mass was found at the inferior lobe of the left lung with multiple calcified lymphadenopathies and signs of parenchymal consolidation. According to these manifestations, the authors suspected the mass was giant tuberculoma accompanied by mediastinal lymphadenopathies and bacterial pneumonia [Figure 3]. Cervical ultrasound showed multiple calcified lymphadenopathies in both cervical regions [Figure 4]. Brain MRI with contrast showed multiple lesions in the midbrain, right occipital lobe, and right caudate nucleus suggesting tuberculoma, and focal leptomeningitis in the bilateral occipital region [Figure 5].

- A 1-year-7-months-old infant with multiple organ tuberculomas who presented with shortness of breath, lumps in the neck and weakness on in both legs and right hand. Anteroposterior projection of chest radiograph showed soft tissue density with unclear margin at left lung field (black arrow). There was also obscuration of the left costo-phrenicus angle.

- A 1-year-7-months-old infant with multiple organ tuberculomas who presented with shortness of breath, lumps in the neck and weakness on in both legs and right hand. (A-C) Mediastinal window in axial, coronal, and sagittal view of nonenhanced chest CT showed homogeneous mass with punctate calcification and air density inside, relatively well-defined, regular margins measuring ± 10.1 x 6.48 x 8.28 cm on inferior lobe of the left lung (black arrow) pushing the left superior lobe and left inferior lower bronchus of the lung left to the anterior and mediastinal organ to the contralateral. (D-F) There were also multiple lymphadenopathies at right paratrachea, subcarina dan right peribronchial (white arrows). Lung window in axial, coronal, and sagittal view of nonenhanced chest CT showed consolidation with air bronchogram sign inside the superior lobe and the medioposterobasal segment of the inferior lobe of the right lung (arrow heads).

- A 1-year-7-months-old infant with multiple organ tuberculomas who presented with shortness of breath, lumps in the neck and weakness on in both legs and right hand. Cervical ultrasound showed (A) normal bilateral thyroid lobes and (B-C) multiple well demarcated, irregular edges, clustered hypoechoic lesions with coarse and peripheral calcification at both cervical region (white arrows) (level II, III, IV, and V).

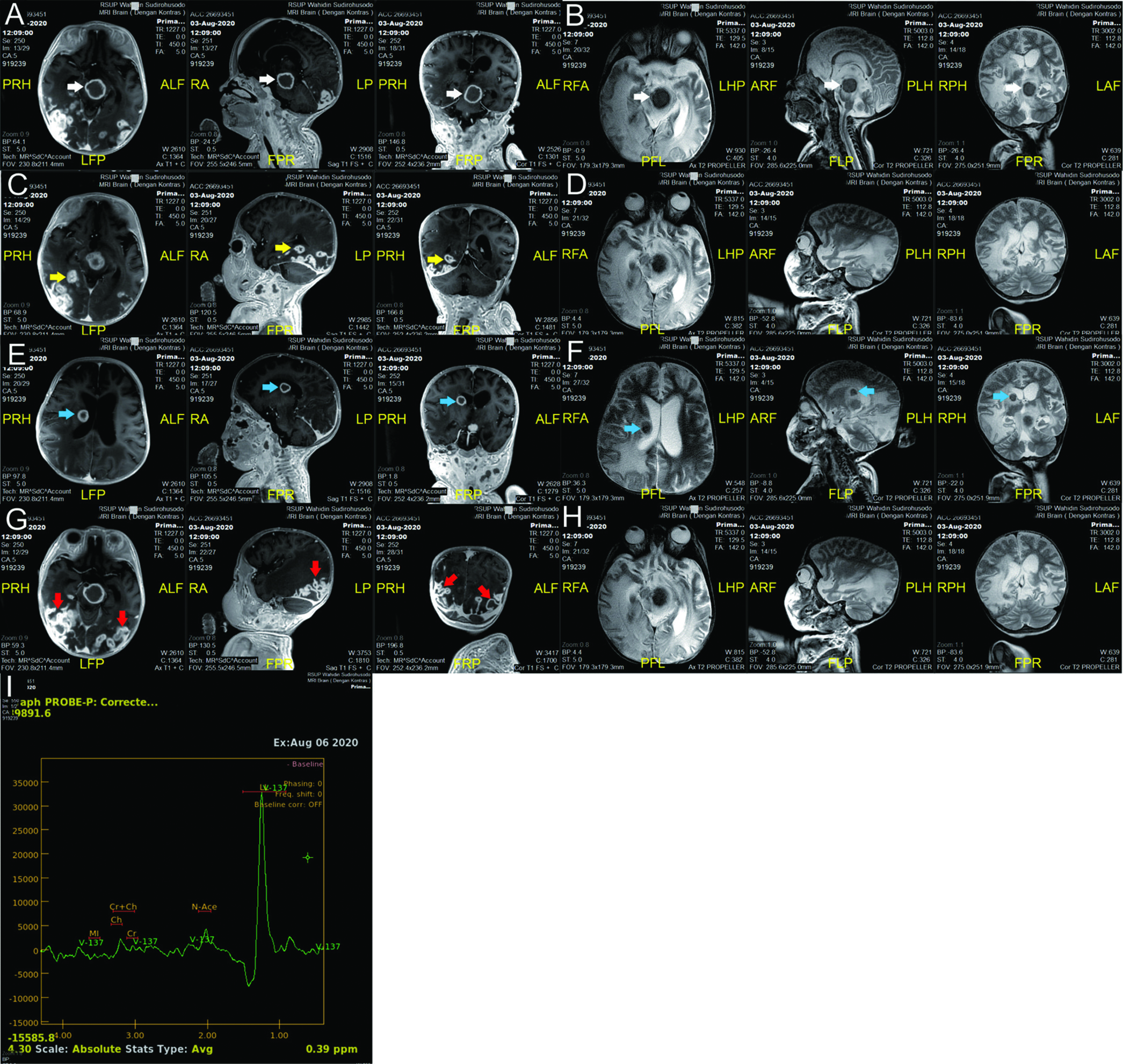

- A 1-year-7-months-old infant with multiple organ tuberculomas who presented with shortness of breath, lumps in the neck and weakness on in both legs and right hand. (A-H) Axial, coronal and sagittal view of brain MRI with contrast showed multiple isointense lesions on T1 with peripheral rim enhancement post contrast, hypointense with slightly hyperintense edges on T2 well-defined, regular surface with perifocal edema in the midbrain (white arrow), right occipital lobe (yellow arrow), and right caudate nucleus (blue arrow) with the largest size ± 2.51 x 2.65 x 2.57 cm. There was also focal enhancement of the sulci and gyri of bilateral occipital region with extensive white matter edema of the bilateral parietotemporooccipital lobes (red arrow), especially the right side. (I) MR Spectrometry showed high lipid-lactate peak.

The following day, Mantoux test was performed with negative induration, but microscopic test from gastric aspiration showed a positive acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear proving an active pulmonary TB. The patient then started the initial regimens of anti-TB drugs with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. An excisional lymph nodes biopsy from the cervical region was then performed to confirm the diagnosis. Histopathological review of the lumps concluded a chronic granulomatous lymphadenitis and supported a TB infection [Figure 6]. However, several days after the biopsy procedure, the patient’s condition worsened followed by desaturation, bradycardia, and finally passed away.

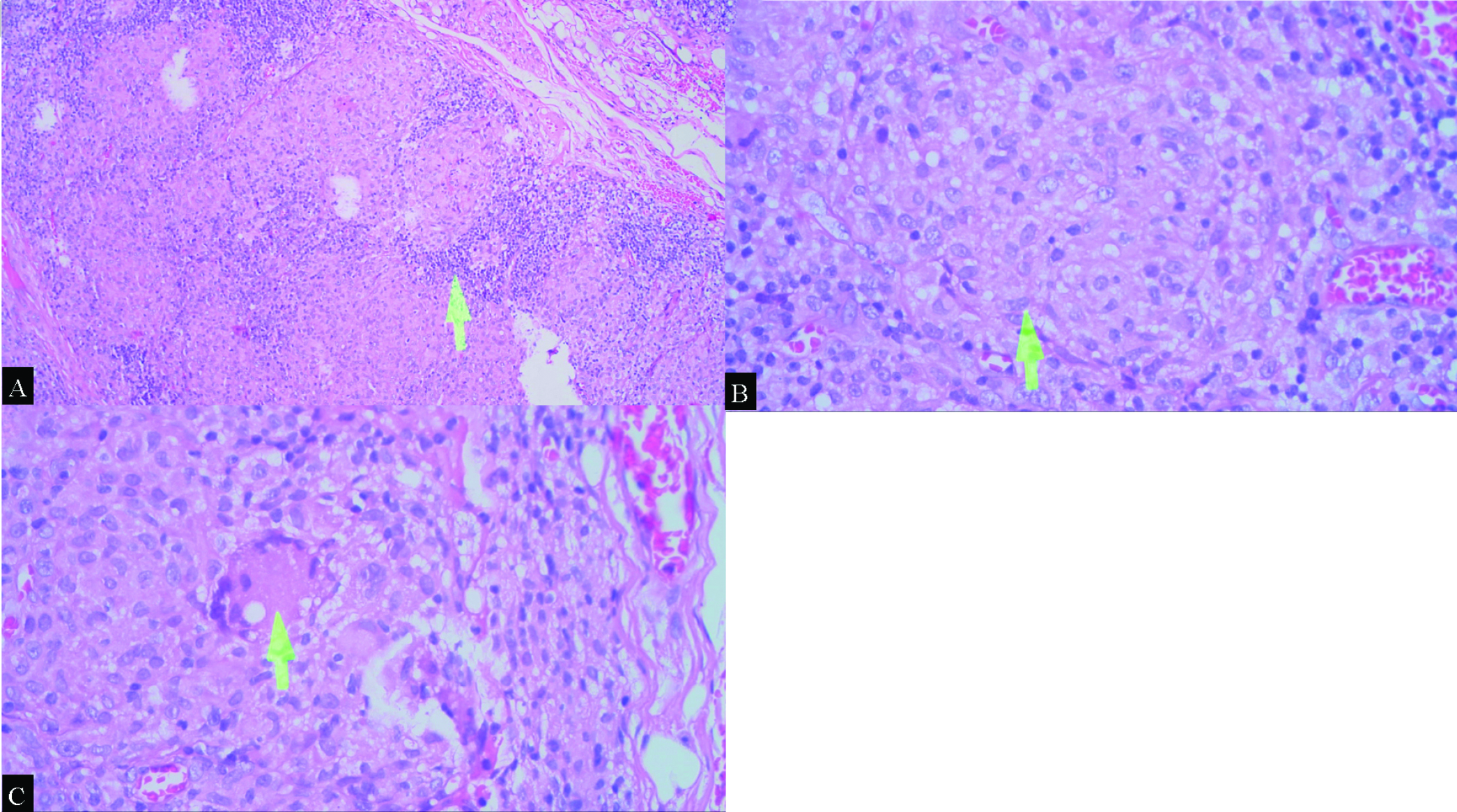

- A 1-year-7-months-old infant with multiple organ tuberculomas who presented with shortness of breath, lumps in the neck and weakness on in both legs and right hand. Histopathological review of the lumps at cervical region, using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E stain) demonstrated (A) granuloma with lymphocytes at the edges (arrow), 20x magnification; (B, C) There were also epithelioid histiocytes (arrow) and Datia Langhans cells (arrow) between the granulomas, respectively. No central caseous necrotic mass formation was seen in this preparation, ×40 magnification.

DISCUSSION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis which is aerobic, AFB, and fastidious,[2] generally occurs in adults and children. As the infection is transmitted through respiratory route, making pulmonary TB the commonest form of TB infection. The bacteria may gain access via the lymphohematogenous route and then affect any organ causing multiple organ TB.[3] Young age and immunological function are two main factors affecting the propensity of disease progression.[4] In this case, TB infection was experienced by a 1-year-7-months-old infant and was suspected due to poor nutritional status that weaken patient’s immune system. This patient was then diagnosed with pulmonary TB in the form of tuberculoma, mediastinal lymphadenopathies and pneumonia, accompanied with extrapulmonary TB in the form of cervical TB lymphadenitis, central nervous system tuberculoma, and focal leptomeningitis.

Diagnosis assessment includes anamnesis, physical examination, and confirmatory examination to detect M. tuberculosis directly by culture, microscopic examination, and NAAT. Another alternative examination is a histopathological examination and screening examination to detect the host’s immune response to pathogens with tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA).[4] The patient has then performed a TST with no induration. But a negative result never eliminates the possibility of TB disease because many extrapulmonary forms of TB can induce anergy to the skin test, as well as host low immune response.[5] Another examination modality by the microscopic test of gastric lavage sampling showed a positive AFB smear which proved the presence of TB infection.

Imaging studies play an important role in diagnosing pulmonary TB and extrapulmonary TB. Chest radiographs is one of the standard examinations in diagnosing TB either in infected patients or in patients with positive TST or IGRA results. Other imaging modalities include computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), depending on the target organ involved.[6] The imaging appearance of pediatric pulmonary TB is different from adults. The most common form of active pediatric pulmonary TB is lymphadenopathy and sometimes parenchymal disease. Tuberculoma is a very common manifestation in adults, but rarely seen in children it appears as a solid pulmonary nodule.[7] From chest radiographs, it was suspected that the left pulmonary mass was confirmed by unenhanced chest CT and was suggested as a giant tuberculoma in the inferior lobe of the left lung. Large tuberculomas with a diameter of 10-11 cm have also been reported. The differential diagnosis of solid pulmonary nodule in children may include metastatic tumor, primary pulmonary neoplasms like pleuropulmonary blastoma, and pulmonary hamartoma.[7] There were also multiple enlarged and calcified lymph nodes in the left paratracheal, subcarinal, and peribronchial regions that were not detected on chest radiographs, yet obviously evaluated on chest CT which is more sensitive in evaluating lymphadenopathy.[3]

Superficial lymphadenopathy is the most common extrapulmonary form of TB which is most commonly involved lymph nodes are anterior cervical, followed by posterior triangle, submandibular, and supraclavicular. Cervical lymph nodes themselves can be involved in various pathological processes, including inflammatory disease, lymphomas, and even metastases.[5] The ultrasonographic appearance of tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis includes hypo-echogenicity, strong internal echoes, echogenic thin layers, nodal matting, soft tissue changes, and displaced hilar vascularity.[8] The patient’s cervical ultrasound showed multiple clustered and enlarged lymph nodes with calcified spots inside which is a strong marker of tuberculous lymphadenitis and then was confirmed by histopathological examination.[8]

Central nervous system TB is rare, developing in fewer than 2% of all cases of TB which is mostly manifest as meningitis and tuberculoma.[5] The most consistent feature of meningitis is diffusely enhancing exudates involving the basal cisterns, but tuberculous meningitis may also be asymmetrical, unilateral and even focal.[3,9] Parenchymal tuberculoma are the most common form of intracranial parenchymal TB with its appearance is differ depend on the stages—noncaseating granuloma, caseating granuloma and granulation with central liquefaction.[9] Brain MRI with contrast found multiple isointense lesions on T1 with peripheral rim enhancement postcontrast, hypointense with slight hyperintense edges on T2 in the midbrain, right occipital lobe, and right caudate nucleus which is in accordance with caseating solid granuloma. MR spectroscopy with high lipid-lactate peak also helpful in diagnosing tuberculoma. A wide variety of differential diagnoses can be considered for the ring-enhancing lesions of tuberculomas. Important ones including neurocysticercosis, tumor metastasis, central nervous system lymphoma (in immunocompromised patients), toxoplasmosis, primary tumors (such as glioblastoma), and pyogenic abscess.[9] In addition, there was also focal leptomeningitis of the bilateral occipital region. This picture is an atypical picture of leptomeningitis and its pathogenesis is also unclear.

As extrapulmonary TB may resemble any other pathology, a confirmatory examination should be performed which is by histopathology examination. Common histopathology features of tuberculoma and tuberculous lymphadenitis include caseous necrosis (specific and sensitive), granuloma, Langhans giant cells, histiocytes, and lymphocytes.[10] Then confirmatory examination with histopathological biopsy was performed on the lump in the neck and found the presence of epithelioid cell granulomas with Langhans cells in between, but no central caseous necrotic mass formation was seen and was concluded as chronic granulomatous lymphadenitis, supporting TB infection. According to Ahmed et al., in TB endemic areas, the presence of granulomatous lesions in the absence of caseous necrosis is considered TB.[10]

CONCLUSION

Tuberculosis (TB) is a systemic infectious disease that may affect almost every organ, generally occurred in adults and children. The nonspecific clinical symptoms of pediatric TB make the diagnosis of often overlooked. Radiological imaging plays an important role in assisting the diagnosis of pediatric TB, but there is no specific feature for TB, so histopathological examination is often required for diagnosis confirmation. The existence of a multidisciplinary approach is expected to assist in the diagnosis of TB in a targeted manner for the earlier proper management of TB.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- The economic burden of tuberculosis in Indonesia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;9:1041-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of child tuberculosis (a cross-sectional study at pulmonary Health Center Semarang City, Indonesia) IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci 2018:1-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modern imaging of tuberculosis in children: Thoracic, central nervous system and abdominal tuberculosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:861-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;4:893-909.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging in extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;56:237-47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large pulmonary solitary mass caused by mimicking a malignant tumor in a child Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Radiol Infect Dis. 2018;5:131-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasonographic features of tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis. J Med Ultrasound. 2014;22:158-63.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic resonance imaging spectrum of intracranial tubercular lesions: One disease, many faces. Pol J Radiol. 2018;83:524-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical study screening for tuberculosis and its histological pattern in patients with enlarged lymph node. Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:417635.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]