Translate this page into:

Glue Embolization of Adrenal Artery Pseudoaneurysm: Case Series with Review of Literature

*Corresponding author: Rajanikant R. Yadav, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Raebareli Road, Lucknow - 226 014, Uttar Pradesh, India. rajani24478@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Israrahmed A, Singh S, Boruah DK, Yadav RR. Glue embolization of adrenal artery pseudoaneurysm: Case series with review of literature embolization of adrenal artery pseudoaneurysm. J Clin Imaging Sci 2020;10:20.

Abstract

Mortality rates for pseudoaneurysm (PSA) rupture are high and immediate intervention in the form of embolization can be life saving for the patient. Adrenal artery PSAs are rare with scarce references in literature. These arteries are small in caliber and require modification of the cannulation techniques for endovascular access. In situations, where the distal artery cannot be cannulated or the ostium cannot be negotiated, and percutaneous direct needle puncture (PDNP) techniques can be used. We discuss two patients with adrenal artery PSA that presented to us and their successful embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate through endovascular and PDNP techniques along with relevant review of the literature.

Keywords

Adrenal artery

Pseudoaneurysm

Embolization

INTRODUCTION

Pseudoaneurysms (PSAs) lack all three layers of the blood vessel and thus, symptomatic or not, are treated due to high risk of rupture.[1] Mortality due to rupture of PSAs are as high as 90–100% versus 12–57% when compared to treated PSA.[2] Literature reports involving adrenal artery PSA are particularly rare.

The formation of PSA has diverse etiologies such as trauma, inflammation (pancreatitis and cholecystitis), infection (abscess), vasculitis, and malignancy.[3] Most common inflammatory causes of PSAs is pancreatitis.

We present two unusual cases of adrenal artery PSA that presented to our department within the past 2 years: One being secondary to pancreatitis and the second due to vasculitis. These were successfully managed by embolization using liquid embolic agent N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue by endovascular and percutaneous direct needle puncture (PDNP) techniques, respectively.

CASES’ DESCRIPTION

Case 1

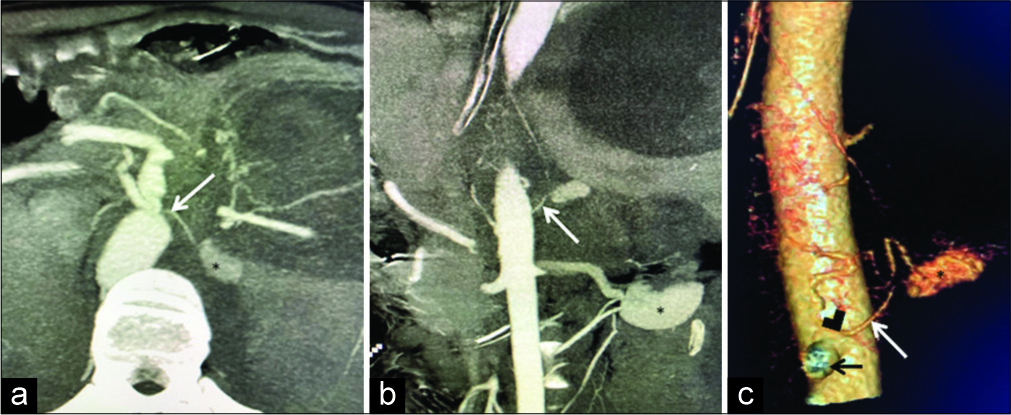

A 20-year-old gentleman with no history of alcohol intake was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis with complaints of persistent, intractable epigastric pain, and vomiting. On 2nd day, he developed tachycardia with a fall in hemoglobin from 11.6 g/dL to 7.6 g/dL within 24 h. An emergent computed tomography angiography (CTA) was performed on a 64-slice multi-detector CT scanner (Philips Ingenuity, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, Ohio, USA) with 90 ml of 300 mg/ml of intravenous non-ionic contrast medium (Omnipaque, GE Healthcare, Marlborough, USA) with automated exposure control. CTA revealed a PSA of approximate size 6 mm×4.4 mm [Figure 1] at left supra renal region with surrounding hematoma and peripancreatic necrotic collections. Maximum intensity projection and volume rendered tomography images demonstrated a PSA arising from the left middle adrenal artery [Figure 1], as a direct branch of the aorta from the left anterolateral aspect. The ostium of the offending vessel was seen arising at D12-L1 level, about 5 mm superolateral to celiac trunk origin. Left inferior phrenic artery was seen arising separately from the coeliac trunk.

- A 20-year-old gentleman diagnosed as acute pancreatitis presented with hypovolemic shock and fall in hemoglobin. Computed tomography angiogram: (a) Axial, (b) coronal, and (c) volume rendered tomography images. A large pseudo aneurysm (*) is seen arising from the left adrenal artery (white arrow). Offending artery is seen arising as a left anterolateral branch of abdominal aorta (black arrowhead in c), just superolateral to coeliac trunk (black arrow in c).

The patient underwent immediate digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Right femoral access was secured with 5 Fr vascular access sheath. A 5-Fr renal double curve (RDC) guide catheter (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, USA) was used and the tip of the catheter negotiated to the expected ostium of left adrenal artery. As the artery was very narrow (~1.3 mm), cannulation was done by wedging the secondary curve of the RDC catheter opposed to the opposite wall of aorta. Selective cannulation of the left middle adrenal artery was done with the help of the microwire (0.18 inch). A 2.7 French (Fr) microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was gently advanced over the microwire. The subsequent angiogram confirmed the PSA arising from the left middle adrenal artery. In addition, delayed filling of the left inferior phrenic artery was seen: Suggestive of collateralization of PSA from the left inferior phrenic artery.

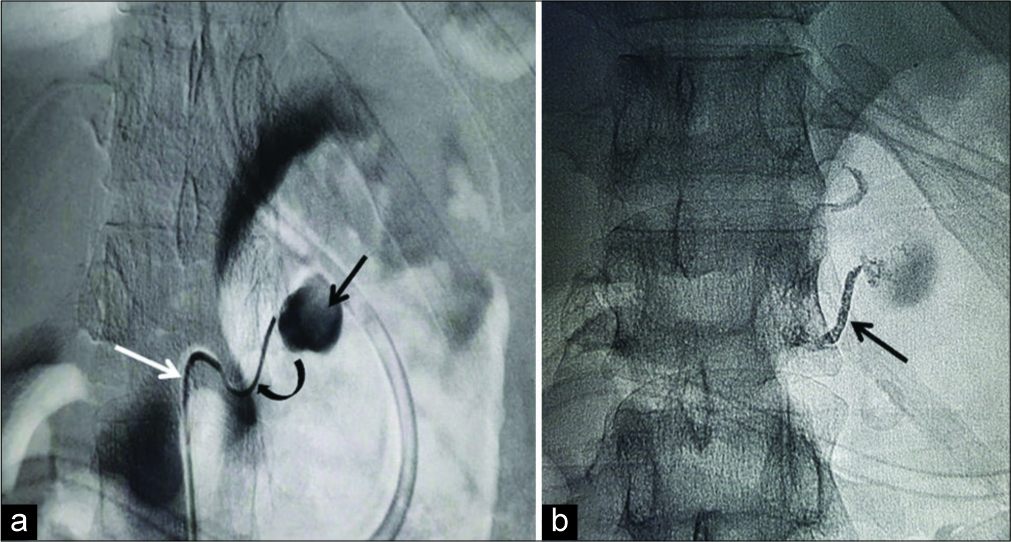

As the distal adrenal artery could not be further negotiated, liquid embolic agent NBCA was chosen as embolic agent. Embolization was performed with a total volume of 0.6 ml of NBCA:ethiodized oil (Lipiodol; Guerbet LLC, Villepinte, France) with a ratio of 1:2 with a prior 5% dextrose flush. The microcatheter was withdrawn immediately to prevent adhesion of catheter tip. Post embolization showed a column of embolic agent completely obliterating the lumens of the left middle adrenal artery and left inferior phrenic artery [Figure 2]. A flush aortogram showed no filling of the PSA and the patients’ vitals reached the normal baseline values.

- A 20-year-old gentleman diagnosed as acute pancreatitis presented with hypovolemic shock and fall in hemoglobin. (a) Digital subtraction angiography shows the pseudoaneurysm (black arrow in a) arising from the left middle adrenal artery. Cannulation was done with RDC catheter (white arrow in a) with coaxially introduced micro catheter (curved arrow in a). (b) Shows a fluoroscopic spot image obtained after trans catheter N-butyl cyanoacrylate: lipiodol (1:3) embolization which shows glue cast in the left middle adrenal artery (black arrow in b).

He was discharged on the 10th post-procedure day with a hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dl. The lesser sac collection had spontaneous communication with posterior wall of stomach.

Case 2

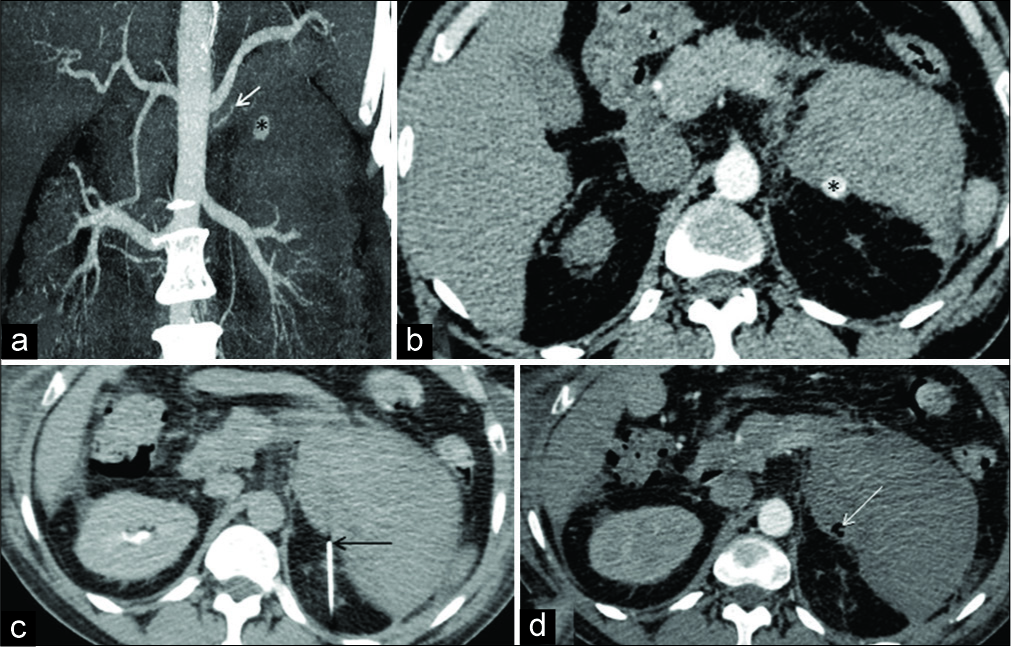

A 50-year-old gentleman with complains of fever, palpable purpura, abdomen pain, malena, and parotitis suggestive of autoimmune disorder, was admitted in our hospital. As anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies in blood and skin biopsy for Henoch–Schönlein purpura were negative. The patient was diagnosed as unclassified vasculitis and started on parenteral steroids. Over subsequent 4 days of admission he had a gradual drop in hemoglobin from 10 g/dl to 5 g/dl. A CTA was done (scanning parameters as case 1), which showed a left middle adrenal artery PSA of size 7.3 mm with a large surrounding hematoma [Figures 3a and 3b].

- A 50-year-old gentleman with a diagnosis of unclassified vasculitis presented in shock with a fall in hemoglobin. Coronal maximum intensity project (a) and axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) angiography (b) shows a small pseudo aneurysm (*) at left supra renal region arising from left middle adrenal artery (white arrow) (c) shows direct puncture of the aneurysm sac under CT guidance with the help of a Chiba needle (black arrow). (d) Axial CT angiographic study performed after embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate shows glue cast (white arrow) with the absence of filling of the pseudo aneurysm sac.

An urgent DSA was performed with intention of endovascular treatment of the PSA. However, the small feeder vessel could not be cannulated and the procedure had to be abandoned. The patient was a poor candidate for surgery due to associated comorbidities and complexity of surgery involving suprarenal region. Ultrasound guided embolization was not feasible as the culprit PSA could not be well localized on ultrasound. The patient was taken up for CT guided intervention, percutaneous direct puncture technique. The patient placed in prone position and a percutaneous retroperitoneal access was taken. A 20 G Chiba needle (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Indiana, USA) was used to puncture the aneurysm sac directly under CT guidance. The position of tip within the aneurysmal sac was established once the free flow of blood was obtained in the trocar, further confirmed on low dose limited CT cuts [Figure 3c]. After a 1 ml 5% dextrose flush, 0.8 ml of undiluted glue (NBCA) was injected through Chiba needle into the sac. Technical success of embolization was confirmed by immediate post-procedure CT angiography which showed the absence of filling of PSA [Figure 3d]. There was no further drop in hemoglobin. However, the patient developed multi-organ failure and respiratory distress syndrome due to underlying disease and eventually succumbed to same after 2 weeks.

DISCUSSION

Both adrenal arteries receive blood supply from set of three arteries: Superior, middle, and inferior adrenal arteries.[4] Superior adrenal arteries arise from inferior phrenic arteries, middle adrenal arteries are direct lateral branches of abdominal aorta and inferior adrenal arteries arise from renal arteries.[4]

Adrenal artery aneurysms and PSAs are very rare with around four case reports in the literature.[4] Nakano et al. have each reported a case of left middle and left inferior adrenal artery aneurysm arising spontaneously and were embolized using micro coils.[4,5] Manners et al. have mentioned about a case of the left inferior adrenal artery aneurysm with extravasation arising spontaneously with embolization done with the help of combination of micro coils and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles.[6] Ikeda et al. have reported a case of post-traumatic left adrenal artery PSA that underwent coil embolization.[7]

However, the involvement of adrenal arteries in pancreatitis and vasculitis has not been documented yet. Here, we have described two cases of adrenal artery PSA managed by endovascular and percutaneous approaches. Large series with vascular complications in relation to pancreatitis have been reported; however, none of them have mentioned adrenal artery PSA as a complication.[8]

The adrenal arteries are small caliber and usually are attenuated further in setting of PSA due to vasospasm thus posing a technical challenge for an interventional radiologist as highlighted by our cases. The first case needed modification in the form of super-selective cannulation by microwire by engaging the ostium with help of RDC. We failed to cannulate the vessel in second case and hence opted for PDNP technique. We attained technical and clinical success in both cases with no procedure related complications.

Endovascular management has several advantages over surgery: Safer, more effective has fewer complications with shorter hospital admissions and faster recovery. Several methods have been described for endovascular treatment of PSAs such as coiling, deployment of covered stents, injecting PVA particles, gel-foam, NBCA, and percutaneous thrombin injection. The treatment method of choice depends on whether the parent culprit vessel can to be sacrificed or its patency has to be preserved.[9] However, the technical and clinical success of these techniques depends on accessibility to distal artery with good trapping of PSA. In scenarios, where the accessibility to the distal part of the artery is not possible due to small caliber of arteries (as in our Case 1), liquid embolizing agents can be used.[3] NBCA polymerizes when it comes in contact with the anions in blood and immediately occludes the vessel. It is mixed with Lipiodol to confer radio-opacity.[9] However, its use requires experience due to risk of reflux, non-target embolization, and adhesion of catheter to the embolized vessel. Hence, it is imperative that the right concentration, volume, and rate of injection of NBCA mixture are pre-decided by taking adequate check angiograms to avoid non target embolization.[3]

A success rate of 79–100% with mortality of 12–33% has been reported with angiographic embolization methods, thus describing the importance of interventional radiological methods in salvaging the patients with PSAs.[10]

CONCLUSION

These two cases highlight rare locations of PSAs arising from the left adrenal artery with different underlying etiologies (pancreatitis and vasculitis) causing life-threatening internal bleeding, and how they were managed successfully despite the small caliber of these vessels with help of minimal modification of the usual techniques.

Ethical statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks for my seniors and colleagues.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- The role of interventional radiology in the management of abdominal visceral artery aneurysms. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012;35:234-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemosuccus pancreaticus: An uncommon cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. A case report. JOP. 2004;5:373-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous direct needle puncture and transcatheter N-butyl cyanoacrylate injection techniques for the embolization of pseudoaneurysms and aneurysms of arteries supplying the hepato-pancreato-biliary system and gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2016;6:48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrenal artery embolization: Anatomy, indications, and technical considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:190-201.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spontaneous ruptured adrenal artery aneurysm. J Urol. 2003;169:614.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radiological treatment of a spontaneously ruptured inferior adrenal artery aneurysm. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:694-8. Availble from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21045799 [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 10]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular management of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms: Transcatheter coil embolization using the isolation technique. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:1128-34. Availble from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20857110 [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 13]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visceral artery aneurysms: Diagnosis and percutaneous management. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2009;26:196-206. Availble from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21326564 [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 19]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular management of major arterial haemorrhage as a complication of inflammatory pancreatic disease. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:591-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Superior mesenteric artery stent-graft placement in a patient with pseudoaneurysm developing from a pancreatic pseudocyst. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:68-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]