Translate this page into:

Double Coronary Artery Anomaly in an Elderly Asymptomatic Patient with Positive Electrocardiogram Stress Test

Address for correspondence: Dr. Giuseppe Cannavale, Department of Radiological Sciences, Policlinico Umberto I, “Sapienza” University of Rome, Viale del Policlinico 155, 00161 Rome, Italy. E-mail: giuseppe_cannavale@hotmail.it

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Malignant coronary artery anomalies and myocardial bridging are more common findings in young patients with cardiac symptoms, but these two associated yet different types of anomalies in an elderly patient has been rarely described. The following case describes the diagnostic use of 128-slice coronary-computed tomography images of an 82-year-old male, former professional soccer player, who reached the age of 82 years without any symptoms of coronary heart disease. In this patient, an association of a malignant coronary artery anomaly of origin and course (left descending coronary artery originating from the right sinus of valsalva running between the aorta and the right ventricular outflow tract), together with a long myocardial bridging over the obtuse marginal branch was diagnosed by multi-slice computed tomography thanks to an initial positive electrocardiogram screening stress test.

Keywords

Coronary artery anomaly

coronary computed tomography

elderly patient

electrocardiogram stress-test

myocardial bridging

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery anomalies of origin and course are relatively common incidental findings at angiography, but they are symptomatic only in a few cases.[1] Furthermore, coronary bridging can be considered common and it rarely has a significant clinical impact.[2] In clinical practice, different conditions may give rise to a positive electrocardiogram (ECG) stress test.

Here, we describe a case of a coronary artery anomaly of origin and course associated with a myocardial bridging, involving two different coronary arteries, in which the first step to achieve the correct diagnosis was a positive ECG stress test.

CASE REPORT

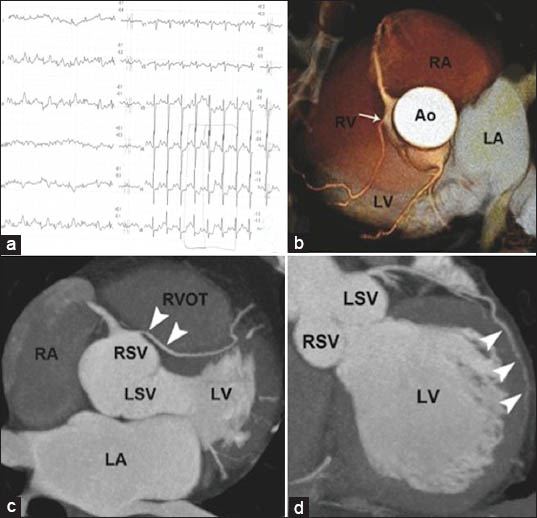

An 82-year-old former professional soccer player was referred to our department for diagnosis of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. His family history was noteworthy because of his father's sudden cardiac death at the age of 35 years. The patient was in good health and did not report any history of syncope or exercise-induced symptoms during his career. Due to the diagnosis of familial hypercholesterolemia, he underwent a screening ECG stress test that showed a 2 mm horizontal ST depression on leads V4 to V6 [Figure 1a], though he showed no symptoms. The echocardiography did not reveal any pathological finding.

- 82-year-old man with positive ECG test but no symptoms diagnosed with an association of a malignant coronary artery anomaly of origin and course and a long myocardial bridging over the obtuse marginal branch. a) 12-lead electrocardiogram stress-test shows the 2 mm horizontal ST depression on leads V4 to V6, in absence of symptoms, during exercise. b) Multislice computed tomography (MSCT) with 3D volume rendering reconstruction reveals the abnormal origin of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery from the right sinus of valsalva (arrow). c) MSCT maximum intensity projection (MIP) reconstruction demonstrates the anomalous course of LAD artery (arrowheads) running between the aorta and the right ventricular outflow tract (malignant variant). d) MSCT MIP reconstruction illustrates the intramural course (“myocardial bridging“) of the obtuse marginal branch (arrowheads) within the left ventricular lateral wall. Ao: Ascending aorta, RVOT: Right ventricular outflow tract, LV: Left ventricle, RSV: Right sinus of valsalva, LA: Left atrium, RA: Right atrium, LSV: Left sinus of valsalva, LV: Left ventricle.

In order to exclude coronary artery disease, the patient underwent a 128-slice coronary-computed tomography (multi-slice CT [MSCT]) scan that revealed abnormal origin of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery from the right sinus of valsalva (RSV) with malignant course of the artery running between the aorta and the right ventricular outflow tract [Figure 1b and c]. Moreover, a long muscular bridge over the obtuse marginal branch originating from the circumflex artery was also demonstrated [Figure 1d]. No evidence of significant obstructive lesions in the whole coronary tree was reported.

Based on the localization of the horizontal ST segment depression on leads V4-V6, the result of the ECG stress test could be probably attributed to the presence of the myocardial bridging of the obtuse marginal branch within the left ventricular lateral wall, rather than to the LAD malignant anomaly.

Since the patient was asymptomatic, only lipid lowering therapy consisting of simvastatin plus ezetimibe was given.[3] The patient is still completely asymptomatic for ischemic heart disease and his low-density lipoprotein and non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are within the range recommended by ATP III guidelines for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia.

DISCUSSION

Coronary artery anomalies can be considered not uncommon, having incidence of 0.6-1.3% among angiographic series and 0.3% in autopsy series.[4] However, LAD arising from the RSV is a rare anomaly with an incidence of 0.017-0.03%.[5] Due to its course between two big vascular structures (the aorta and the pulmonary artery trunk or the right ventricular outflow tract), it is considered a malignant variant and known to be associated with increased risk of sudden death, especially in young athletes.[6] Cardiovascular symptoms (i.e., chest pain, exertional dyspnea, syncope, or dizziness) occur in 18-30% of all cases of coronary anomalies. However, in our case, the patient was completely asymptomatic and reached the elderly age of 82 years without any cardiac-related symptoms despite his athletic career.[7] ECG stress test is generally considered of little diagnostic value, but coronary angiography and MSCT are valuable tools in achieving a diagnosis.[8]

As coronary anomalies, myocardial bridges are congenital in origin and it has been estimated that an average of 30-50% of adults have myocardial bridges.[4] Most of the myocardial bridges do not produce symptoms and the diagnosis is usually an incidental finding, as in our case. However, muscular bridges over the circumflex artery are a rare anomaly, as the bridging in most cases is located over the LAD.[8] In the absence of symptoms, no therapy for myocardial bridges is recommended.

CONCLUSION

In our elderly patient, the concomitant association between a malignant coronary artery anomaly and a muscular bridge, a finding rarely described before, raises the hypothesis that coronary artery anomalies and myocardial bridges may share a similar developmental pattern, as is suggested for the association between muscular bridging and coronary arterial dominance.[910] ECG stress test, usually considered of little value for detection of coronary anomalies, was in our case the first diagnostic clue leading to the final diagnosis.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2013/3/1/68/124106

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Coronary artery anomalies‐Current clinical issues: Definitions, classification, incidence, clinical relevance, and treatment guidelines. Tex Heart Inst J. 2002;29:271-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myocardial bridging on coronary CTA: An innocent bystander or a culprit in myocardial infarction? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2012;6:3-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anomalous origin of the left main coronary artery from the right sinus of Valsalva with an intramural course identified by transesophageal echocardiography in a 14 year old with acute myocardial infarction. Cardiol Rev. 2005;13:219-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary artery anomalies in 126,595 patients undergoing coronary arteriography. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1990;21:28-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aberrant coronary artery origin from the aorta. Diagnosis and clinical significance. Circulation. 1974;50:774-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exercise-unrelated sudden death as the first event of anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the right aortic sinus. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:437-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical profile of congenital coronary artery anomalies with origin from the wrong aortic sinus leading to sudden death in young competitive athletes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1493-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relationship of myocardial bridges to coronary artery dominance in the adult human heart. J Anat. 2006;209:43-50.

- [Google Scholar]