Translate this page into:

Different Sonographic Faces of Ectopic Pregnancy

Address for correspondence: Dr. Nishant Gupta, Department of Radiology, St. Vincent's Medical Center, 2800 Main Street, Bridgeport, CT, USA. E-mail: drngupta20@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Vaginal bleeding in the first trimester has wide differential diagnoses, the most common being a normal early intrauterine pregnancy, with other potential causes including spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is approximately 2% of all reported pregnancies and is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality worldwide. Clinical signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy are often nonspecific. History of pelvic pain with bleeding and positive β-human chorionic gonadotropin should raise the possibility of ectopic pregnancy. Knowledge of the different locations of ectopic pregnancy is of utmost importance, in which ultrasound imaging plays a crucial role. This pictorial essay depicts sonographic findings and essential pitfalls in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy.

Keywords

Ectopic pregnancy

extrauterine pregnancy

human chorionic gonadotropin

pelvic pain

transvaginal ultrasound

Introduction

Implantation of developing blastocyst at a site other than endometrium results in ectopic pregnancy. It is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality.[1] Dominant risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease, assisted reproductive techniques, and prior tubal surgery.[2] Clinical features include pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, and adnexal mass. Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice and with transvaginal pelvic sonography; an intrauterine pregnancy can be seen as early as 5 weeks with a high level of confidence. The presence of intrauterine pregnancy essentially rules out ectopic pregnancy with the rare exception of heterotopic pregnancy, in which ectopic pregnancy coexists with intrauterine pregnancy.[2] Differential diagnoses for nonvisualization of intrauterine pregnancy in a patient with a positive serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) test include an early pregnancy, miscarriage, pregnancy of unknown location, and ectopic pregnancy.

Imaging Techniques

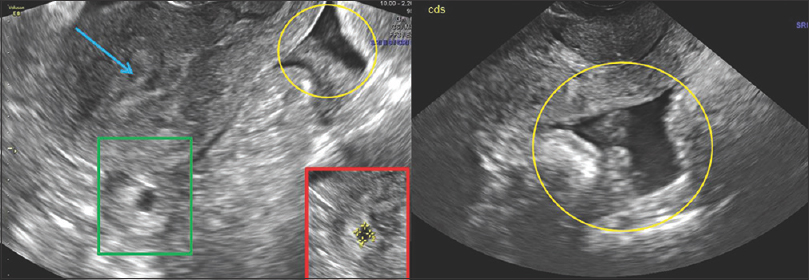

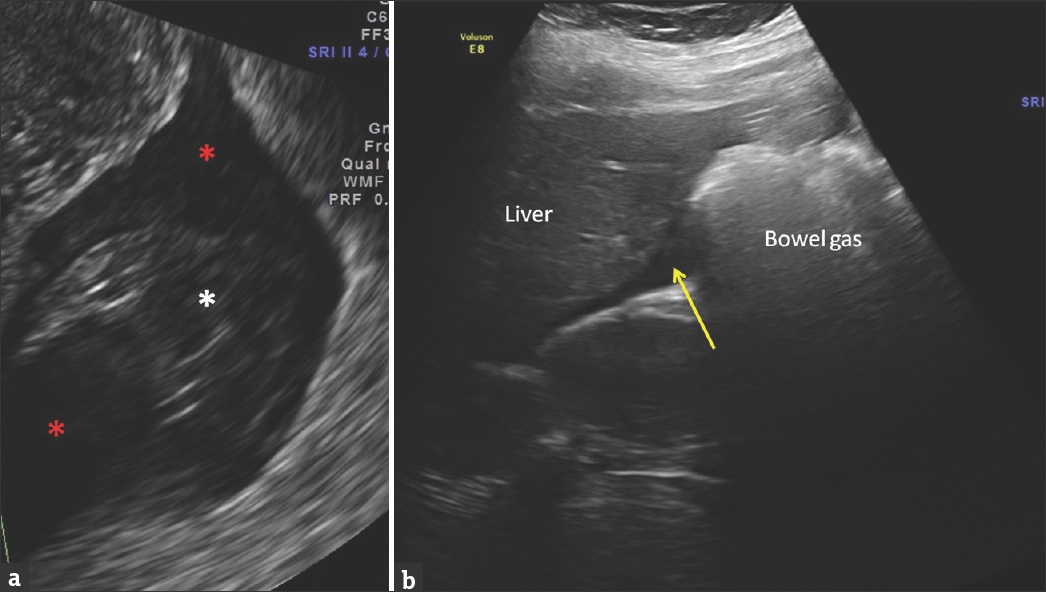

Pelvic sonography is performed in both sagittal and transverse planes, with both transabdominal and transvaginal approach. Extrauterine mass and free fluid in the pelvis are important clues.[3] Free fluid with floating debris or low-level internal echoes is highly suspicious for hemoperitoneum secondary to ruptured ectopic pregnancy [Figure 1]. Imaging of paracolic gutters, perihepatic, and perisplenic region [Figure 2] should be performed to quantify the amount of hemoperitoneum.[23] Transvaginal pelvic sonography provides improved visualization of the endometrium, endometrial cavity, and gestational sac. A collection of blood and debris in the endometrium, also known as pseudosac can be seen in about 20% ectopic pregnancies.[2] Adnexa are well depicted on transvaginal pelvic sonography. Color and pulsed Doppler techniques play an important role in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy. On color Doppler images, hypervascular ring with low impedance also referred as “Ring of Fire” in the ovary is a helpful sign but not diagnostic of ectopic pregnancy. It is also seen with corpus luteal cyst where its incidence is more common than ectopic pregnancy.

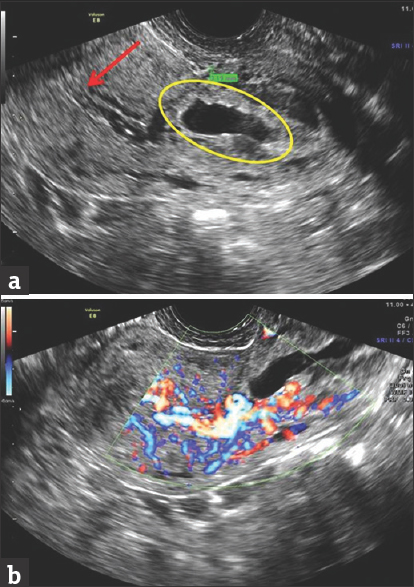

- 29-year-old pregnant female with last menstrual period 8 weeks ago, presented with acute onset lower abdominal pain and hypotension. Transabdominal longitudinal pelvic ultrasound image shows empty endometrial cavity (blue arrow), with a distended tubal structure (green box), posterior to the uterus. There is a moderate amount of mixed echoes in the cul-de-sac (yellow oval), consistent with clot/blood. These findings are highly suspicious for ruptured tubal pregnancy. Inset-red box shows magnified image with tubal ectopic pregnancy.

- A 29-year-old pregnant female last menstrual period 8 weeks ago (same patient as Figure 1), presented with acute onset lower abdominal pain and hypotension. Magnified ultrasound image of posterior cul-de-sac (a) shows fluid with internal echoes (red asterisks) and clots (white asterisk). Fluid seen in Morrison's pouch near liver is consistent with hemoperitoneum from ruptured ectopic pregnancy (b).

In patients with a negative sonographic examination and a positive β-hCG, about 5%–20% ectopic pregnancies can be detected on repeat ultrasound examination. Patient with negative sonographic examination should be followed by serial β-hCG levels, and a repeat sonogram must be performed in 48 h.[2] 3D ultrasound may help in delineating the gestational sac. In difficult cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be obtained.

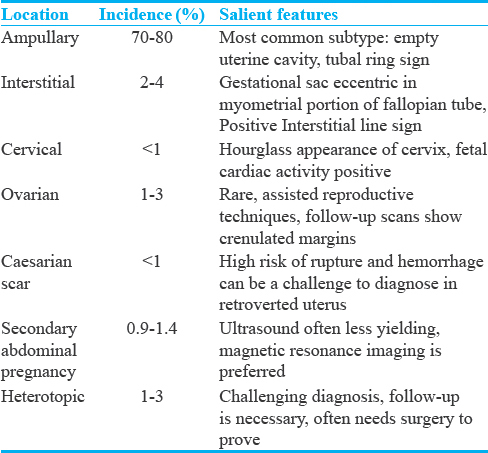

Subtypes of Ectopic Pregnancy by Location

Various subtypes of ectopic pregnancies are mentioned with their salient features are mentioned in Table 1.

Tubal pregnancy

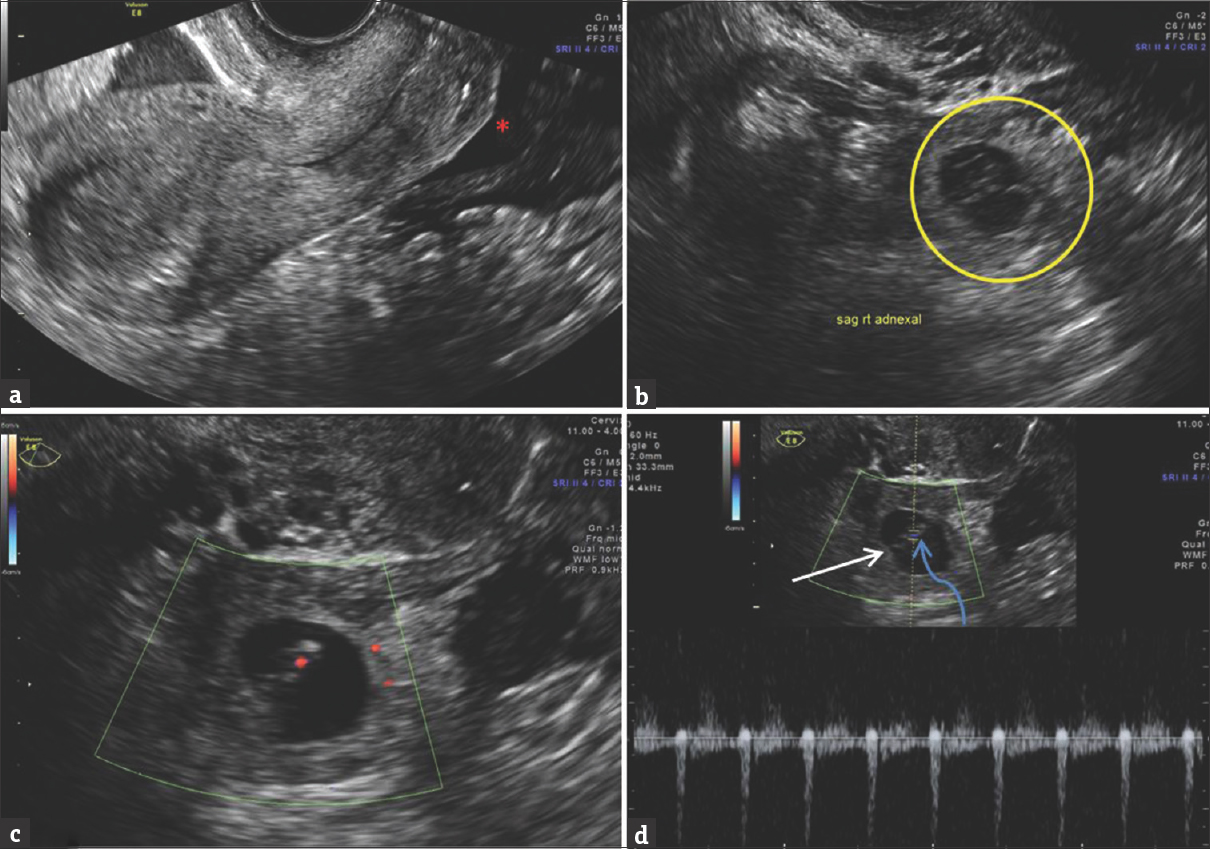

The most common site of ectopic pregnancy is the fallopian tube,[34] accounting for nearly 95% cases. In the fallopian tube, the ampulla (70%–80%) is the most common site [Figure 3], followed by an isthmus (12%) [Figure 4] and fimbria (5%).[5] On imaging, live embryo outside endometrium is the most specific sign. Adnexal mass separate from the ovary is also a very specific sign.[34] Adnexal mass can be differentiated from the ovary while doing transabdominal ultrasonography by pressing with the transducer, which will displace the mass from the ovary. Similarly, while performing transvaginal sonography, the adnexal mass can be differentiated from the ovary by pressing the mass with one hand while performing the transvaginal scan with the other hand. Tubal ring sign in tubal pregnancy is a hyperechoic ring surrounding an extrauterine gestational sac.

- A 32-year-old female with last menstrual period 6 weeks ago and positive history of pelvic inflammatory disease in the past, presented with acute onset low-grade right lower quadrant pain. Transverse transvaginal pelvic sonography shows a round gestational sac (white arrows) in the ampullary portion of the right fallopian tube, containing the yolk sac (white asterisk). Fetal pole is not seen at this early gestational age.

- 32-year-old female with LMP 9 weeks ago and right lower quadrant pain. (a) Midsagittal transvaginal pelvic sonogram shows no intra-uterine gestation sac. Fluids and clots in cul-de-sac (red asterisk). (b) Right parasagittal sonogram shows heterogeneous right adnexal structure (yellow circle), signifying right tubal ectopic pregnancy. (c) Zoomed and Color Doppler imaging shows color flow in the fetal pole with cardiac activity. (d) Transverse Spectral Doppler reveals a gestational sac (white arrow) with an embryo (curved blue arrow) in isthmic portion of right fallopian tube with intact cardiac activity.

Interstitial pregnancy

Implantation of a blastocyst in the myometrial portions of the fallopian tube is a less common cause (2%–4% cases) for ectopic pregnancy.[5] Risk factors include pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), prior salpingectomy, and in vitro fertilization. Sonographically, gestational sac is identified eccentrically in the myometrial portion of fallopian tube [Figure 5] and is surrounded by thin layer of myometrium that measures <5 mm.[5] Interstitial line sign has been described as a specific sign of interstitial pregnancy, which is described as an echogenic line extending into the upper portion of the horn of uterus, bordering the intramural portion of gestational sac.[5]

- A 24-year-old Hispanic female with positive urine β-human chorionic gonadotropin, presented with acute onset severe cramping pain in the right lower pelvis. Patient's last menstrual period was 9 weeks ago. Transverse transvaginal pelvic gray scale sonogram (a) and color Doppler image (b) through the uterine fundus shows an eccentrically located gestational sac (red arrows), deforming the external uterine contour (blue arrow) with thinning of the overlying myometrium, consistent with an interstitial ectopic pregnancy. The endometrial cavity is empty (yellow arrow).

Cervical pregnancy

Cervical ectopic pregnancy is a very rare type (<1%). It is important to recognize this type because of the potential of life-threatening hemorrhage if dilatation and curettage is attempted. Gestational sac in the cervical canal gives hourglass configuration to uterus [Figure 6]. On color Doppler imaging, the hypervascular trophoblastic ring is seen [Figure 7]. The most important differential of cervical ectopic pregnancy is ongoing abortion with gestational sac within the cervical canal. Salient differentiating features include no hypervascular trophoblastic ring around the ongoing abortion, which is due to the absence of trophoblastic tissue around the aborting gestational sac, which forms the basis of sliding sign.[4] The sliding sign is elicited while performing transvaginal pelvic sonography and is the sliding of the gestational sac within the cervical canal while applying soft pressure with the probe.[6] Other sonographic signs of ongoing abortion include lack of cardiac activity, open internal os, flattened gestational sac, and gravid uterus approximately enlarged for patient's dates.[45]

- A 25-year-old female with lower central pelvic pain. Patient's reported last menstrual period was 12 weeks ago. Longitudinal transabdominal scan (a and b) shows an empty endometrial cavity (green arrow) and a low-lying gestational sac (yellow oval). Distension of cervix leads to “hourglass” configuration (orange drawing of hourglass). Transvaginal scans (c and d) show a gestational sac with an embryo (red asterisk) and yolk sac (white arrow) implanted in the cervix (calipers in d).

- A 29-year-old pregnant female presented in the emergency department with vaginal bleeding. Patient's reported last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago. Longitudinal transvaginal ultrasound (a) shows an empty endometrial cavity (red arrow). A flattened gestational sac (yellow oval) is seen in the cervix, without distinct yolk sac or embryo. The chance of viability is near minimal. Color Doppler images (b) show increased extensive vascularity around the gestational sac, signifying trophoblastic vascularity.

Ovarian pregnancy

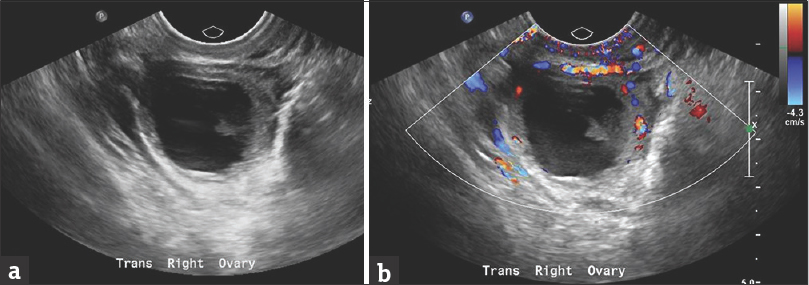

Ovarian pregnancy occurs when the ovum is fertilized in the distal fallopian tube and subsequently is implanted in the ovary. It is rare, accounting for 1%–3% of ectopic pregnancies.[2] It is strongly associated with the use of intrauterine devices and PID. On ultrasound, a gestational sac is seen in the ovary [Figure 8]. Very rarely, a live fetus can be seen. Care should be taken to differentiate it from corpus luteal cyst which is much more common than ovarian ectopic.[23] Wall of corpus luteal cyst is thinner and more hypoechoic than the ectopic gestational sac. If the patient is stable, follow-up ultrasound may show progressive involution and increasing crenulation of its margins.[5]

- A 35-year-old female on treatment for assisted reproductive technique, presented with positive urine pregnancy test and right lower abdominal pain. Patient's last menstrual period was 10 weeks ago. Transvaginal transverse pelvic sonography (a) and color Doppler (b) shows the cystic lesion within the right ovary, with an eccentric echogenic component. Patient was operated due to high suspicion for ovarian ectopic pregnancy, which was proven intraoperatively.

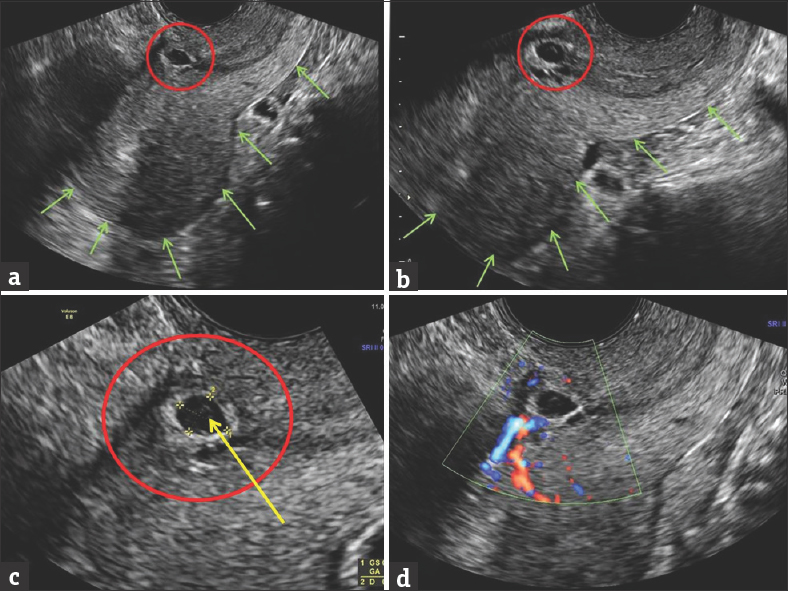

Cesarean scar pregnancy

It is the rare type (<1% cases), in which gestational sac is implanted in the scar tissue of cesarean section. If cesarean section scar does not heal well, it can result in focal thinning that may be susceptible to implantation of the gestational sac. It may result in uterine rupture and life-threatening hemorrhage.[5] On ultrasound, gestation sac is seen at cesarean section scar site at the anterior inferior edge of uterine cavity [Figure 9]. It is important to obtain a sagittal image to show the relationship of cesarean section scar to gestational sac.[5] MRI can be used in difficult cases, in which relationship of cesarean section scar with gestational sac is not clear.[7]

- A 31-year-old multiparous female presented with spotting. Last menstrual period was 7 weeks ago. Longitudinal transvaginal sonogram (a and b) shows an oval fluid collection in the region of anterior lower uterine segment (red circle). Uterine wall is extremely thin anteriorly, increasing chances of wall dehiscence. Green arrows outline the posterior uterine contours. This is a typical site for cesarean section scar ectopic pregnancy. Magnified view (c) shows gestational sac (red circle), and fetal pole (yellow arrow). Color Doppler image (d) shows trophoblastic activity.

Secondary abdominal pregnancy

This is a rare subtype (0.9%–1.4% cases) of ectopic pregnancy, which can go undetected until very late gestational age. It occurs when the gestational sac is implanted in the abdominal cavity outside the uterus, fallopian tube, and ovaries. Implantation can occur on omentum, vital organs, or great vessels.[8] On ultrasound, fetus and placenta are seen outside the uterus. Fetal parts are seen close to the maternal abdominal wall.[2] MRI is extremely helpful in localizing placenta and its adherence to vital organs.

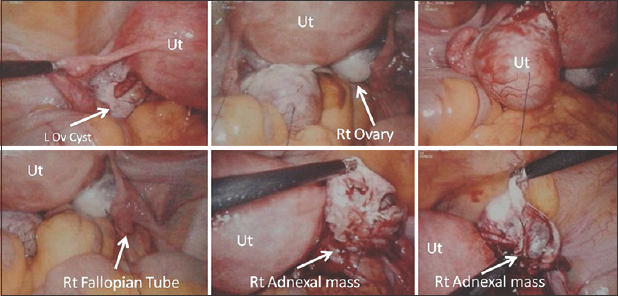

Heterotopic pregnancy

It occurs when there is simultaneous intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancy [Figure 10]. Its incidence is higher with assisted reproductive techniques (1%–3%). Differential diagnoses include intrauterine pregnancy with corpus luteal cyst. Unlike other ectopic pregnancies, β-hCG levels and doubling time are normal in heterotopic pregnancy, which is the reason why these pregnancies are difficult to diagnose.[29] Heterotopic pregnancy can be treated with laser ablation of ectopic pregnancy or laparoscopic removal [Figures 11 and 12].

- 32-year-old female during routine first trimester scanning. LMP was 7 weeks ago. Transverse transvaginal scan shows a gestational sac (red circle) with fetal pole (white arrow) within the endometrial cavity. Fetal cardiac activity (image b). Adjacent to the right ovary (yellow circle), a separate heterogeneous multicystic mass was identified (blue arrow). Magnified cystic component showed a yolk sac (orange arrow), consistent with another gestation sac in the right fallopian tube. Case of heterotopic pregnancy. Small free fluid in anterior cul-de-sac (red asterisk).

- A 27-year-old female on assisted reproductive treatment. Last menstrual period was 8 weeks ago. Longitudinal transvaginal pelvic sonogram (a) shows a gestational sac (yellow circle) with a yolk sac (red arrow) within endometrial cavity. B-mode ultrasound (b) shows a fetus (green arrow) with positive fetal cardiac activity. Right adnexa (c) shows a heterogeneous mass (blue circle), with a gestational saclike structure (green circle), containing an embryo (calipers in image e). No cardiac activity is peripheral trophoblastic flow was identified (f). Left ovary showed a large cyst, consistent with a corpus luteum (left ovary in image d).

- A 27-year-old female on assisted reproductive treatment. Laparoscopic images of the same patient as in Figure 11, showing the uterus, left ovarian cyst, right ovary, right fallopian tube. Right adnexal mass is shown, which was identified as right ectopic pregnancy lying just adjacent to the fimbrial end of the right fallopian tube. Patient had a viable intrauterine pregnancy. This was a surgically proven case of heterotopic pregnancy.

Imaging of ectopic pregnancy postmedical management

After methotrexate treatment, the ectopic pregnancy becomes large in the first 2 weeks because of hemorrhage; therefore, it is not recommended to scan before 2 weeks and follow with a decrease in β-hCG. However, the size of ectopic mass may diminish slower than the decrease in β-hCG levels.[10] Alternately, the initial increase in the size of ectopic mass must not be concluded as failure to treatment.

Conclusions

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is increasing because of increasing use of assisted reproductive techniques, PIDs, and sexually transmitted diseases. Pelvic sonography plays a pivotal role in diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and its location. An early diagnosis is crucial to prevent catastrophic outcomes and initiate prompt and appropriate treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2017/7/1/6/200570

References

- Trends in ectopic pregnancy mortality in the United States: 1980-2007. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:837-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sonographic evaluation of ectopic pregnancy. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007;45:549-60. ix

- [Google Scholar]

- Uncommon implantation sites of ectopic pregnancy: Thinking beyond the complex adnexal mass. Radiographics. 2015;35:946-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and treatment of early cervical pregnancy: A review and a report of two cases treated conservatively. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;8:373-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic resonance imaging as an adjunct to ultrasound in evaluating cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2013;3:16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging unusual pregnancy implantations: Rare ectopic pregnancies and more. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:1380-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ultrasonographic appearance of tubal pregnancy in patients treated with methotrexate. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2585-7.

- [Google Scholar]