Translate this page into:

Angiogenesis Imaging in Neoplasia

Address for correspondence: Dr. David J. Bowden, Department of Radiology, Box 219, Addenbrooke's Hospital and University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK. E-mail: davidjbowden@googlemail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Angiogenesis plays a key role in physiological and pathophysiological processes and is recognized as being essential for tumor growth and metastases. The recent oncological development of anti-angiogenic drugs brings with it a need for angiogenesis quantification and monitoring of response. The nature of these agents means that traditional anatomical methods of assessing morphologic change are outmoded and functional imaging techniques and/or agents are necessary. Herein, we describe the various imaging techniques that can be employed to assess angiogenesis, along with their inherent advantages and disadvantages and discuss the current and future developments in the field.

Keywords

Angiogenesis

dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

molecular imaging

positron emission tomography

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis is essential in physiological processes such as wound healing and the menstrual cycle; however, it also plays a key role in pathophysiological processes such as diabetic retinopathy, tumor growth, and metastasis. The ability of tumor cells to induce new vessel formation through angiogenesis was initially described by Judah Folkman.[1] This theory has led to the development of anti-angiogenic agents in cancer therapy. At present, eight anti-angiogenic drugs have gained FDA approval for oncological use, along with two further agents with anti-angiogenic properties.[2] Such agents fall within three broad categories: (1) monoclonal antibodies targeting factors in the angiogenic cascade such as the anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) bevacizumab, (2) small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) of multiple pro-angiogenic growth factor receptors (e.g. sorafenib), and (3) inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a protein involved in the intracellular angiogenesis cascade (e.g. temsirolimus). The development of these agents has resulted in the requirement for imaging assays that can quantify the degree of angiogenesis and therefore monitor response to these agents. Anti-angiogenic agents differ from traditional chemotherapeutic agents in several ways, but importantly they tend to be tumoristatic, rather than tumoricidal. As a result, reductions in tumor size are likely to occur over a longer time period than with standard chemotherapy. Therefore, the “Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors” (RECIST) criteria that are widely used to assess treatment response in oncology by anatomical imaging methods do not apply. Methods of functional imaging are required in order to quantify angiogenesis and illustrate tumor treatment response independently of size changes.

ANGIOGENESIS THEORY AT A CELLULAR LEVEL

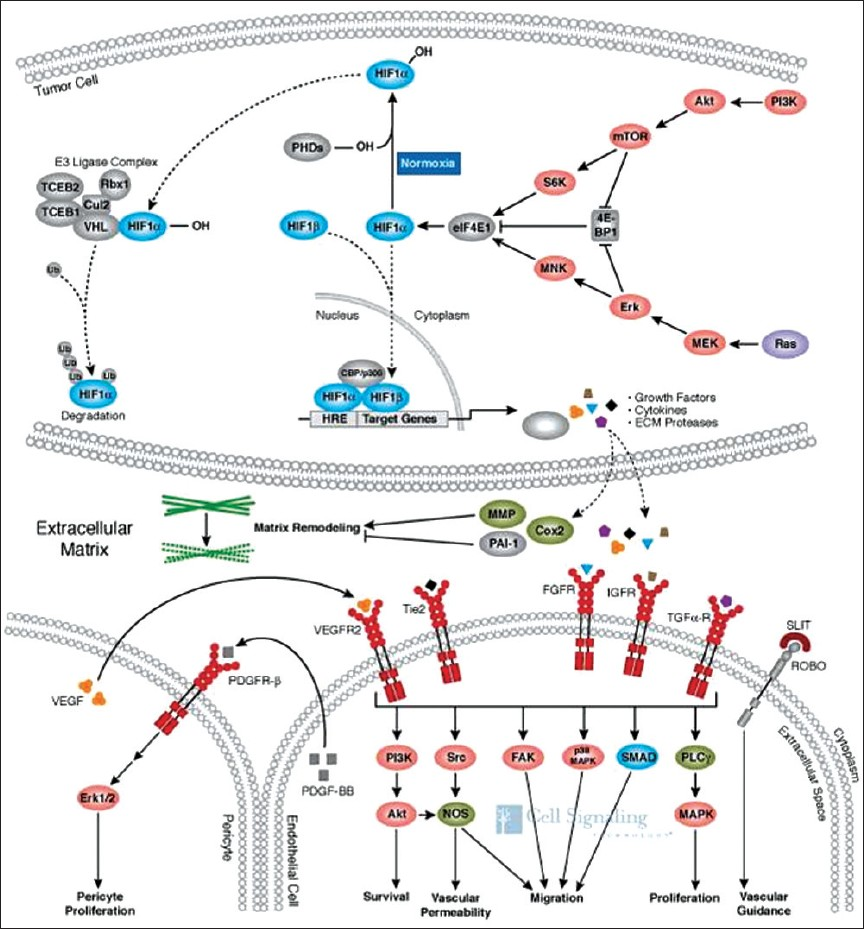

Angiogenesis is defined as growth of new blood vessels from the existing vessels. This process is essential for tumor growth beyond 1–2 mm, since passive diffusion alone becomes insufficient.[3] As with physiological angiogenesis, the primary stimulus to this neovascularization is hypoxia. Under normoxic conditions, the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is reduced to its inactive state; however, under hypoxic conditions, it becomes activated, leading to downstream transcription of pro-angiogenic factors and cytokines [Figure 1]. Following release, these factors bind to endothelial growth factor receptors, stimulating proliferation and the formation of new vessels. Under normal physiological control, the process of neovascularization is tightly regulated; however, in tumors, this regulation is disrupted with the result that new vessels are disorganized, with no hierarchical structure, and are tortuous with multiple gaps between the cells.[4] Such characteristics can be exploited when attempting to image angiogenesis.

- Under normoxic conditions, the transcription factor HIF-1α is degraded (curved dotted line). In hypoxia, it accumulates with subsequent translocation to the nucleus (straight dotted line), resulting in the expression of numerous genes involved in cell signaling and growth. The end result is endothelial and pericyte proliferation with new vessel formation. (Reproduced with permission from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) (http://www.cellsignal.com/reference/pathway/Angiogenesis.html).

QUANTIFYING ANGIOGENESIS

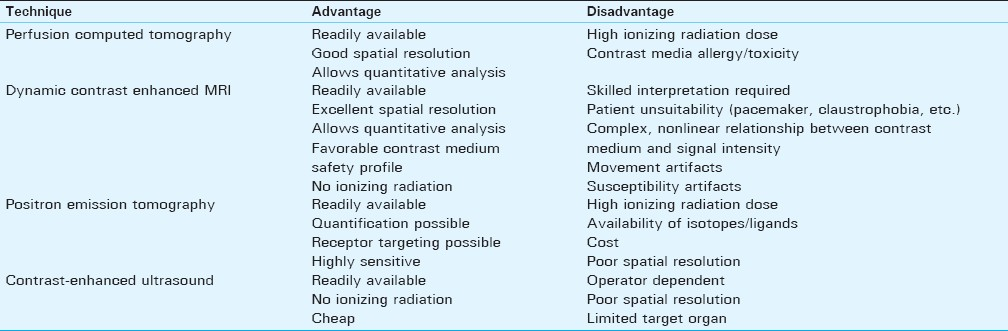

Microvascular density (MVD) measurement, a histological technique, has to date represented the traditional “gold-standard” method of quantifying angiogenesis. However, since MVD measurement requires a biopsy, it is inherently invasive and is therefore an ex vivo test. As a result, functionality cannot be demonstrated. Furthermore, tumor angiogenesis is known to be heterogeneous and hence the MVD is prone to sampling bias, potentially under- or over-estimating the degree of angiogenesis according to the tumor area biopsied.[5] A means of quantifying angiogenesis by imaging is appealing because it has the potential to overcome all of these limitations. Imaging is not invasive and therefore allows multiple assessments. The emergence of new technologies [e.g. perfusion analysis utilizing 128-slice computed tomography (CT)] has enabled the entire tumor to be analyzed to avoid sampling bias, and since the test is performed in vivo, functionality can be demonstrated. Methods of imaging angiogenesis can be divided into two broad categories: “non-targeted” modalities/contrast agents that exploit properties of the tumor micro-environment and "targeted" modalities/contrast agents that are directed at specific markers of angiogenesis. The relative merits and disadvantages of imaging modalities currently available in clinical practice are summarized in Table 1and are discussed further below.

ANGIOGENESIS IMAGING: NON-TARGETED METHODS

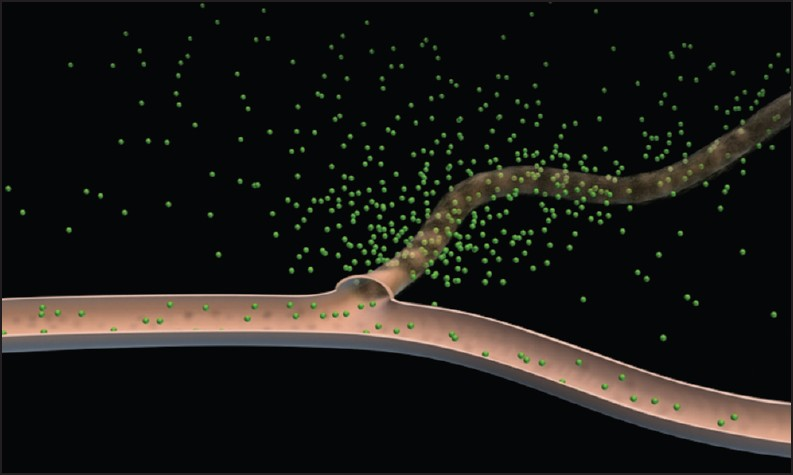

Non-targeted methods exploit the previously described chaotic, hyper-permeable nature of tumor blood vessels. Low-molecular weight (LMW) contrast agents are predominantly retained by vessels with normal, intact endothelia, but easily pass through the “leaky” tumor endothelia [Figure 2]. Essentially, all modalities that use LMW agents have the potential to image angiogenesis in this way and, to a greater or lesser extent, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT, and ultrasound (US) have all been trialed.

- Schematic diagram depicting leakage of an intravenous contrast agent through leaky tumor vessels; normal vessels are relatively impermeable to such agents (Adapted with permission from Barrett et al. EJR 2006; 60(3): 353-366).

Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI

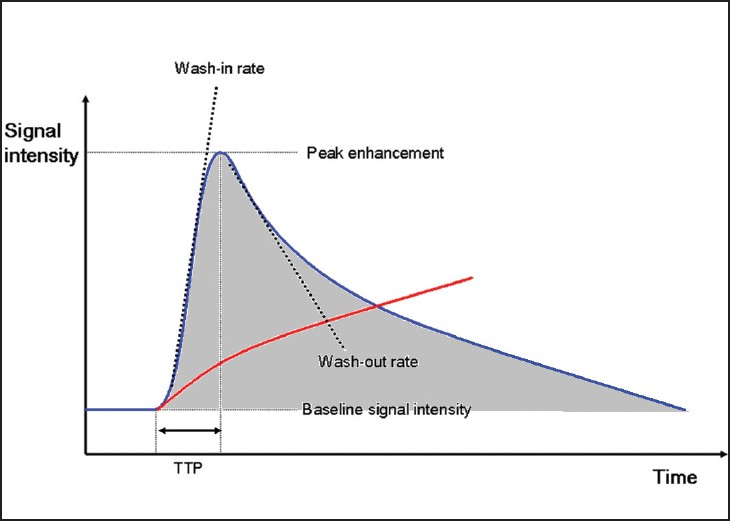

Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI is a technique whereby a standard low-molecular weight Gadolinium agent is administered intravenously at a standard rate, followed by sequential imaging of a region of interest (ROI) within the target lesion for up to 30 minutes. Signal intensity changes are measured within the ROI relative to normal tissue and plotted against time, allowing analysis of contrast “wash-in” and “wash out” components of the enhancement curve [Figure 3]. Simple semi-quantitative analysis is performed by assessing the nature of such curves, an example being the evaluation of breast lesions.[6] The slope of the wash-in and wash-out components of the curve, time to maximal enhancement [or time to peak (TTP)] and area under the curve (AUC) provide semi-quantitative data that can be utilized to derive information on tumor blood flow, concentration, and tissue permeability.[7] From these data, additional metrics such as mean transit time (MTT), a measure of the time taken for blood to perfuse a tissue, can be derived. Drawbacks of this method include the influence of protocol parameters such as contrast agent concentration, rate of injection, and variation in imaging hardware settings.

- DCE-MRI enhancement curves for normal tissue (red) and malignant tumor tissue (blue). TTP = time to peak enhancement within tissue; area under the curve (AUC) = shaded region. Wash-in and wash-out rates represent the velocity of enhancement and velocity of loss of enhancement, respectively, and together with AUC reflect underlying characteristics of tumor microvasculature that facilitate tumor classification and differentiation.

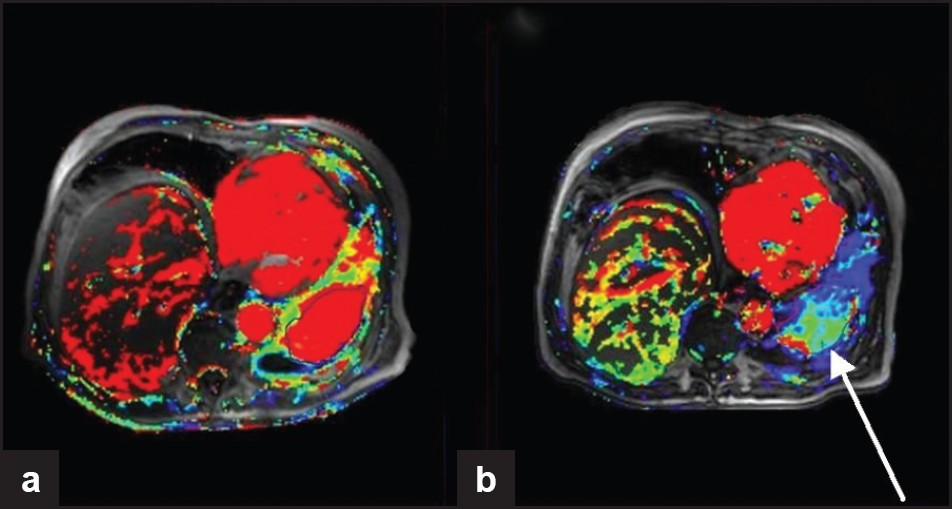

Alternatively, post-processing techniques based on kinetic modeling can be applied wherein a computer analyzes the contrast enhancement patterns on a pixel-by-pixel basis to derive quantitative measures of permeability [Figure 4]. Parameters such as Ktrans (a measure of blood flow and permeability) and kep (the reverse flow constant) are obtained, thereby serving as markers of angiogenesis. DCE-MRI benefits from the widespread availability of MR, a lack of ionizing radiation, the transferability of protocols to existing scanners, and the use of standard gadolinium-based agents. Indeed, DCE-MRI has been studied in Phase II and III chemotherapeutic trials of anti-angiogenic agents and remains the most widely adopted imaging method for quantifying angiogenesis.[8] However, DCE-MRI is not without its problems. The required post-processing and additional interpretation add to the reporting time; realistically an MR physicist needs to be on site, which is not possible in every center. In addition, the relationship of gadolinium concentration to signal intensity is not linear and depends on the T1 relaxivity of the tissue imaged – this can be partially overcome by the acquisition of a T1 map. Furthermore, there is disagreement on the optimal kinetic model to use and although the selection of an arterial input function should aid standardization, it often results in an additional variable. These problems mean that standardization is still an issue, making comparison between centers problematic.

- DCE-MRI from a clinical trial of sorafenib (anti-angiogenic agent targeting VEGF and PDGF) for the treatment of squamous cell lung cancer. Ktrans maps (a measure of tumor permeability) obtained at (a) baseline and (b) 6 weeks after treatment. Although there is little change in lesion size, the Ktrans maps show reduced vascularity (arrow) indicating successful anti-angiogenic therapy.

DCE-CT

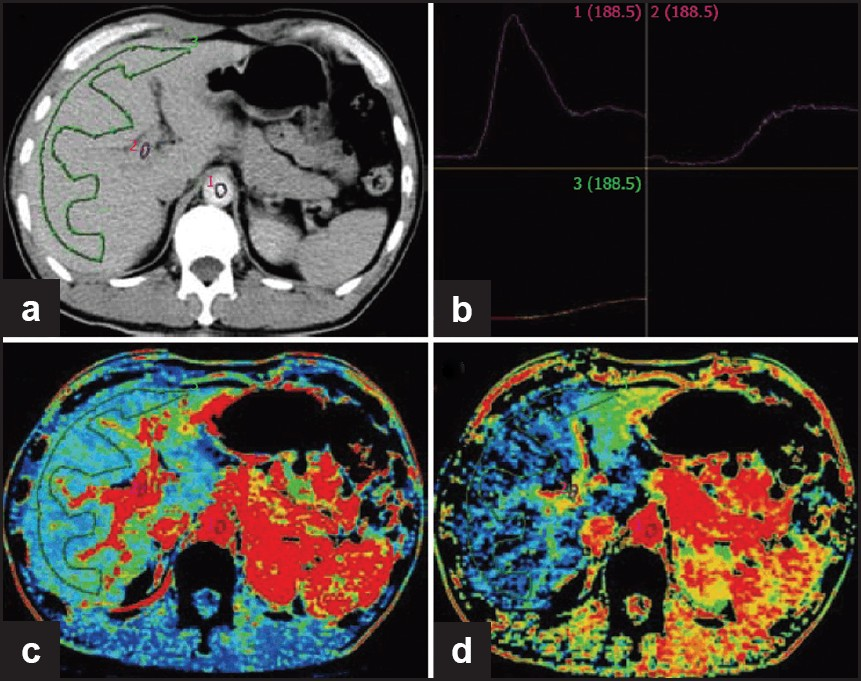

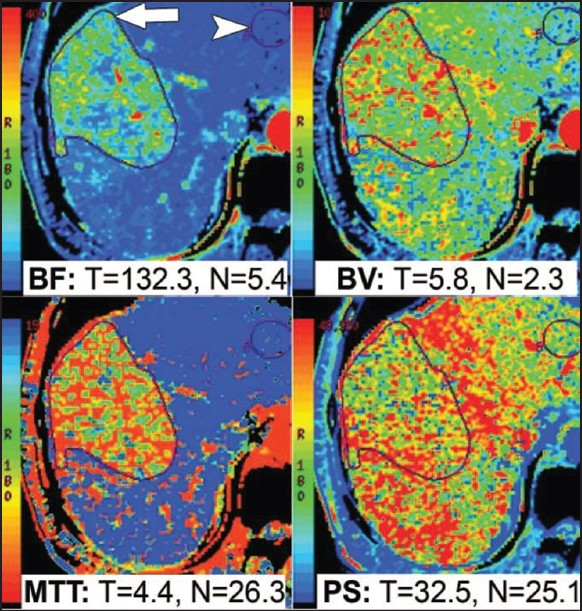

DCE-CT follows similar principles to perfusion CT brain imaging for stroke assessment. Measures of permeability, blood flow, blood volume, and MTT can now be routinely acquired for tumors as part of clinical practice. The development of modern, 128-slice CT hardware with accompanying software advances has allowed both whole organ and tumor perfusion analysis, and has resulted in a rapid growth of research in this field.[9] In this technique, a baseline unenhanced study is typically obtained of the organ or tissue of interest. Following the administration of a bolus of intravenous iodinated contrast medium, repeated, rapid imaging of the tissue is performed over a period of up to several minutes and attenuation levels measured within the area(s) of interest. From these data, a time–attenuation curve is derived, and through complex mathematical algorithms involving de-convolution and compartmental analysis, a wide range of physiological parameters are derived. Data may subsequently be presented as both quantitative measurements and graphical representation of blood flow [Figure 5]. The method has been validated for the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and has the advantage of good reproducibility, benefiting from the linear relationship of iodine concentration to attenuation values [Figure 6].[10] The acquisition of such functional data has enabled the objective measurement of changes in tumor perfusion following different chemotherapeutic regimes, including transcatheter chemoembolization (TAE). Indeed, animal CT perfusion studies have demonstrated that following TAE, there is a subsequent increase in vascular permeability and stimulation of tumor angiogenesis.[9] Such data are likely to prove of significant importance in the evaluation of the future effectiveness of antivascular therapies. However, drawbacks of DCE-CT include the relatively high radiation dose, of particular concern given the need to repeat studies at multiple time intervals when monitoring anti-angiogenic therapy.

- Normal liver perfusion image. (a) Selection of ROI at aorta, portal vein and liver; (b) time-density curve (TDC) for ROI (upper left: aorta; upper right: portal vein; lower left: liver); (c) pseudo-color image of hepatic blood flow; (d) pseudo-color image of hepatic arterial perfusion index (Reproduced with permission from reference 9).

- CT perfusion functional maps of blood flow (BF), blood volume (BV), permeability surface area (PS), and mean transit Time (MTT) in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma in the right lobe of the liver. Preferential arterial supply to the tumor results in higher BF, BV, and PS values and a lower MTT value, as shown here (Reproduced with permission from reference 8).

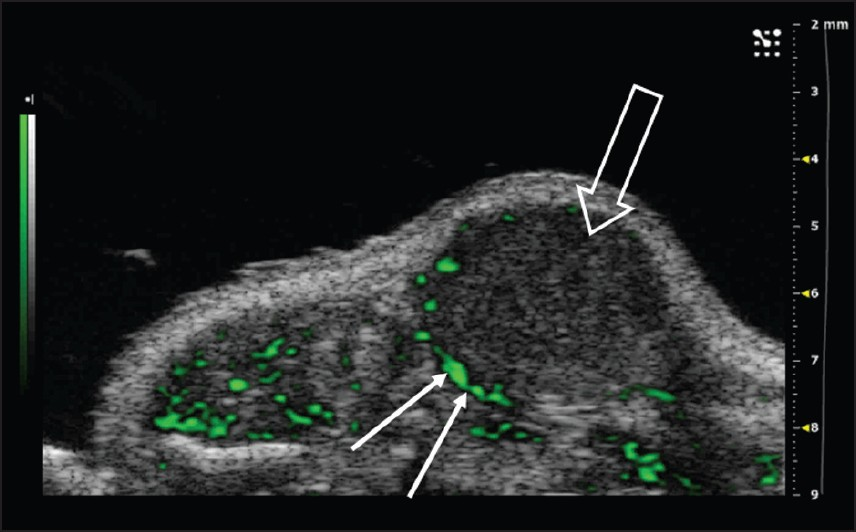

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) involves the administration of intravenous microbubble contrast agents with subsequent ultrasound imaging. Such agents are typically 2–5 μm in diameter and are composed of a lipid or polymer shell containing a variety of gases (nitrogen, perfluorocarbons) [Figure 7].[11] CEUS requires little additional training for those competent at ultrasound (US) and as such is probably the most translatable to non-specialist centers. However, the technique suffers from a lack of quantification, and access to certain anatomical areas is limited (lung, brain, deep structures).

- Nonlinear contrast agent imaging in the mouse abdomen. Non-targeted Vevo MicroMarker® Contrast Agents (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) were injected intravenously through a tail vein cannulation. Post-processed green contrast overlay aids in the visualization of the contrast agent and highlights the areas of increased blood flow in the periphery of the tumor, an area where angiogenesis is maximal (arrows); tumor indicated by open arrow (Reproduced with permission from http://www.visualsonics.com/contrast-mode).

ANGIOGENESIS IMAGING: TARGETED METHODS

Targeted imaging of angiogenesis involves the use of contrast agents that specifically target markers of angiogenesis. Potential targets include any of the factors involved in the angiogenic pathway, such as integrins that are over-expressed on angiogenic vessels, or growth factor receptors such as Vascular Endothelial Growth factor (VEGFR) or Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGFR) . Potential targeting moieties include monoclonal antibodies to any of these targets, or glycopeptides containing the arginine-glycine-aspartic (RGD) tripeptide sequence that bind the integrins α5β1, αvβ3, and αvβ5. A challenge to this type of imaging is the relatively low number of targets available; thus, the modalities need to be highly sensitive in order to detect low concentrations of the agents. Of the currently available imaging modalities, only single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) have sufficient sensitivity to overcome this problem.

PET/SPECT

PET has a 10-fold higher sensitivity than SPECT and is able to detect picomolar concentrations of a tracer. It has the advantage of whole body 3D display, and the wider availability of PET-CT has overcome the problem of poor spatial resolution. New PET probes have been developed and have been tested pre-clinically, for example, probes targeting VEGF receptors and probes incorporating 18F-labeled RGD glycopeptides for targeting the integrin αvβ3 [Figure 8].[12]

![Correlation of tracer accumulation and αvβ3 expression in a soft tissue sarcoma of the knee. (a) [18F]-Galacto-RGD PET study demonstrating peripheral tracer uptake in the tumor (arrow). (b) Fused sagittal PET-CT image shows intense isotope uptake within enhancing tumor wall; no isotope uptake is seen within its non-enhancing center. (c) Immunohistochemistry of peripheral tumor using the anti-αvβ3 monoclonal antibody LM609 shows intense staining of tumor vasculature (Reproduced with permission from reference 10).](/content/12/2011/1/1/img/JCIS-1-38-g009.png)

- Correlation of tracer accumulation and αvβ3 expression in a soft tissue sarcoma of the knee. (a) [18F]-Galacto-RGD PET study demonstrating peripheral tracer uptake in the tumor (arrow). (b) Fused sagittal PET-CT image shows intense isotope uptake within enhancing tumor wall; no isotope uptake is seen within its non-enhancing center. (c) Immunohistochemistry of peripheral tumor using the anti-αvβ3 monoclonal antibody LM609 shows intense staining of tumor vasculature (Reproduced with permission from reference 10).

Optical imaging

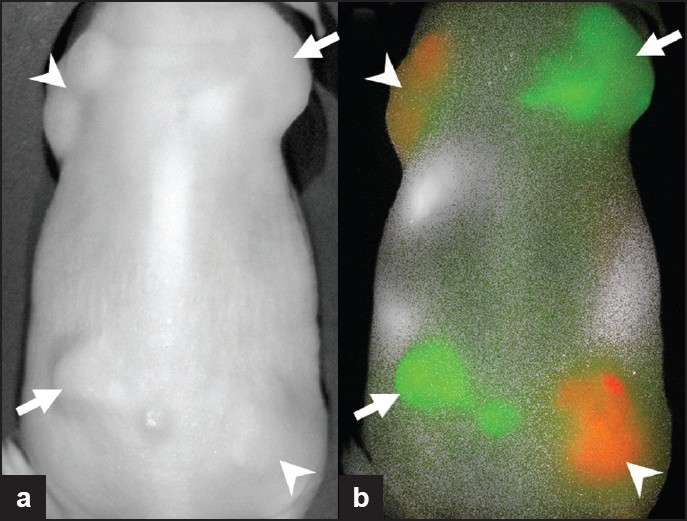

Optical imaging provides sufficient sensitivity to enable targeted imaging [Figure 9]. Optical imaging utilizes agents that emit in the near-infrared range of the optical spectra and have a better penetration than fluorophores emitting at lower wavelengths. Despite this, the technique remains hindered by the limited depth penetration (typically 1–2 cm) and realistically only has potential for endoscopic procedures. Another limitation is the toxicity profile of the agents in current use. It should be noted that optical imaging is more cost-effective than the other modalities for the purposes of drug development.

- Subcutaneously implanted tumors expressing HER1 (arrowheads) or expressing HER2 receptors (arrows). Two optically labeled antibodies, Cy5.5-cetuximab (anti-HER1; red) and Cy7-trastuzumab (anti-HER2; green), were injected and imaging was performed. The tumors cannot be differentiated on (a) the white light image, but with (b) fluorescence imaging, the two different tumor types are clearly distinguished.

Targeted MRI

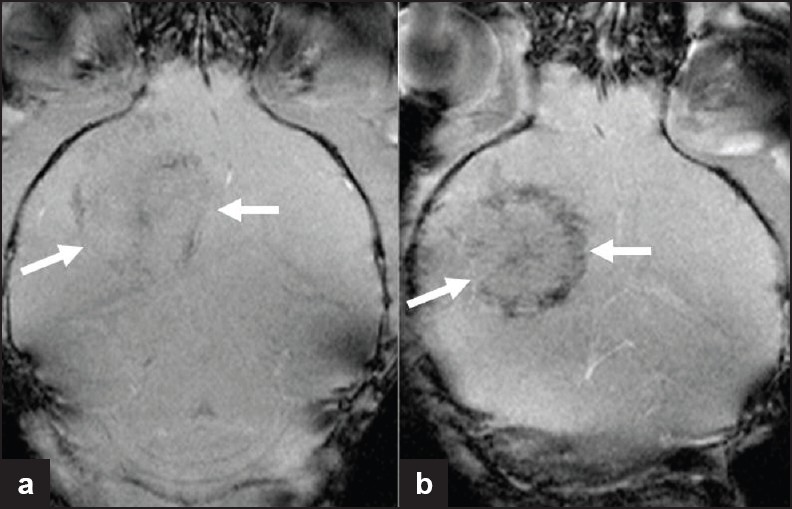

Although MRI lacks the sensitivity of the other modalities discussed, targeted imaging has been made possible by the novel technique of “endothelial stem cell” MRI. This involves the labeling of endothelial progenitor stem cells and the subsequent tracking of their behavior in vivo.[13] Labeling possibilities include the use of iron particles which have a beneficial safety profile although these have the disadvantage of being “negative” contrast agents. Labeled cells are injected intravenously 3–5 days prior to imaging and subsequently migrate to areas of increased endothelial proliferation/neovascularization (up to 40% track to tumors), thereby providing a method of angiogenesis imaging [Figure 10].

- Iron-labeled endothelial precursor cell imaging in a murine glioma model. MR images of tumor after implantation of (a) unlabeled and (b) iron-labeled 6stem cells. Histology confirmed the presence of iron within the tumor, secondary to tracking of the labeled cells to regions of increased endothelial proliferation/neo-vascularization. This is noted to be predominantly at the tumor periphery, where angiogenesis is maximal (Reproduced with permission from reference 5).

IMAGING ANGIOGENESIS IN PRACTICE: PREDICTING PATIENT OUTCOME

Currently accepted methods for determining tumor response following treatment include quantitative assessment of tumor burden and size using criteria such as the RECIST. Such techniques have failed to include tumor metrics that reflect tissue vascularity and therefore fall short of adequately measuring the response to anti-angiogenic therapies. However, recent studies have shown that by the use of imaging techniques such as perfusion CT, early anti-angiogenic treatment effects can be demonstrated in addition to enabling the prediction of progression-free survival and outcome at the end of treatment courses in the treatment of HCC.[14] In addition, perfusion CT has been shown to predict biologic response of metastatic renal cell carcinoma to anti-angiogenic drugs such as sorafenib and sunitinib and has been shown capable of detecting tumor response following only a single cycle of treatment.[15] Such developments have not been restricted to CT. MR perfusion studies have also shown the capability of this technique in predicting response to anti-angiogenic therapy in pancreatic carcinoma,[16] whilst both 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) and DCE-MRI studies have been used to identify patients most likely to benefit from anti-angiogenic therapy in non-small cell lung cancer.[17] It is evident that the explosion of translational research in this arena has already started to influence clinical practice in the treatment of a wide variety of tumor types.

CONCLUSION

The imaging of angiogenesis has advanced from a scientific curiosity to an important tool in the assessment of new drugs. Development of new oncology drugs means traditional methods of measuring morphologic change are outmoded and functional imaging techniques/agents are necessary. Targeted angiogenesis agents appeal; however, there are problems to overcome, for example, the high sensitivity required and relatively poor signal to noise ratio. Some methods described are already widely used for assessing response to anti-angiogenic agents, while others are nearing clinical utilization. Future directions in the field are likely to center on the development and refinement of targeted agents, in which PET will play a key role. A basic knowledge of angiogenesis imaging and future developments is therefore essential to the general radiologist practicing today.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2011/1/1/38/83229

REFERENCES

- The Angiogenesis Foundation, Cambridge MA. Available from: http://www.angio.org/providers/oncology/fda_approved_therapies.html

- [Google Scholar]

- New perspectives in clinical oncology from angiogenesis research. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:2534-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Openings between defective endothelial cells explain tumor vessel leakiness. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1363-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dynamic breast MRI: Are signal intensity time course data useful for differential diagnosis of enhancing lesions? Radiology. 1999;211:101-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiogenesis: An integrative approach from science to medicine. 2008. Boston: Springer; :322-33. Refer 90 http://ccr.ncifcrf.gov/Staff/publications.asp?profileid=5728&display=all

- [Google Scholar]

- DCE-MRI biomarkers in the clinical evaluation of antiangiogenic and vascular disrupting agents. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:189-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical application of hepatic CT perfusion. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:907-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advanced HCC: CT perfusion of liver and tumor tissue--Initial experience. Radiology. 2007;243:736-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Noninvasive visualization of v3 integrin in cancer patients by PET and [18F]Galacto-RGD. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection of migration of locally implanted AC 133+ stem cells by cellular magnetic resonance imaging with histological findings. FASEB J. 2008;22:3234-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring response to antiangiogenic treatment and predicting outcomes in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using image biomarkers, CT perfusion, tumor density, and tumor size (RECIST) 2011. Invest Radiol. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2151239613.(Epub ahead of print) refer pubmed

- [Google Scholar]

- Metastatic renal carcinoma: Evaluation of antiangiogenic therapy with dynamic contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology. 2010;256:511-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic cancer: Utility of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging in assessment of antiangiogenic therapy. Radiology. 2010;256:441-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring response to antiangiogenic therapy in non-small cell lung cancer using imaging markers derived from PET and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:48-55.

- [Google Scholar]