Translate this page into:

Afferent Loop Syndrome with Intestinal Ischemia due to Internal Hernia after Whipple Operation for T2N1M0 Pancreatic Cancer

*Corresponding author: Marijan Pejic, Department of Radiology, University of South Florida, 2 Tampa General Circle, STC 7028, Tampa, Florida, United States. MarijanPejic@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Pejic M, Parsee AA. Afferent loop syndrome with intestinal ischemia due to internal hernia after Whipple operation for T2N1M0 pancreatic cancer. J Clin Imaging Sci 2020;10:43.

Abstract

Afferent loop syndrome is an uncommon complication of Whipple procedure. The often vague and non-specific presentation results in difficulty and/or delay in diagnosis, which may lead to bowel ischemia or perforation. CT can demonstrate characteristic features, yield the diagnosis of afferent loop syndrome, and predict the cause before surgical intervention. We present a rare etiology of acute afferent loop syndrome in a patient 6 weeks after Whipple procedure who was reportedly recovering well, which resulted in prompt surgical intervention.

Keywords

Afferent loop syndrome

Whipple procedure

Internal hernia

Pancreatic cancer

Intestinal ischemia

INTRODUCTION

Afferent loop syndrome (ALS) is an uncommon complication of a Whipple procedure with a reported incidence of 0.3–1.0%.[1] The etiologies of ALS are adhesions, kinking at the anastomosis, stomal stenosis, volvulus, internal hernia, intussusception, and obstruction from masses (such as locoregional recurrence of cancer) or inflammation (including radiation enteritis).[2] Obstruction of the afferent loop results in accumulation of secretions and elevated intraluminal pressure. The often vague and non- specific presentation results in difficulty and/or delay in diagnosis, which may lead to bowel ischemia and perforation. We present a rare etiology of ALS which resulted in prompt surgical intervention.

CASE DESCRIPTION

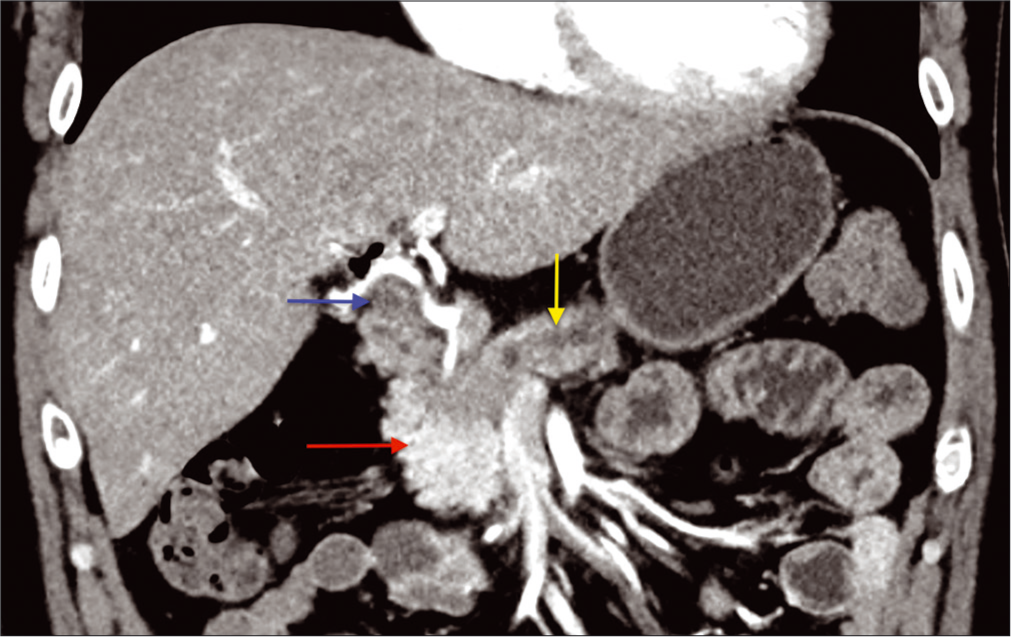

A 40-year-old male presented with jaundice, dark urine, pruritus, and 20 lbs of unintended weight loss. Elevated laboratory values included a bilirubin of 4.7 mg/dL, ALT of 328 U/L, and CA-19-9 of 104 U/mL. A CT abdomen/pelvis demonstrated a 2.7 cm pancreatic head mass with biliary and pancreatic ductal dilation [Figure 1]. An endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration yielded moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma with mucinous features. Two weeks after the biopsy, the patient developed acute cholangitis and sepsis. Three days later, the patient underwent robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy, portal lymph node dissection, cholecystectomy, and intra- abdominal omental flap. One porta hepatis lymph node was positive for metastasis and the final pathology was T2N1. The resection margin was negative. The patient was discharged and had been reportedly feeling well.

- A 40-year-old male presented with jaundice, dark urine, pruritus, and a 20 lb unintended weight loss. Initial CT abdomen with IV contrast, coronal image demonstrates a hypo-attenuating pancreatic head mass measuring 2.7 cm (red arrow). There is resultant obstructive pancreatic (yellow arrow) and biliary ductal dilation (blue arrow).

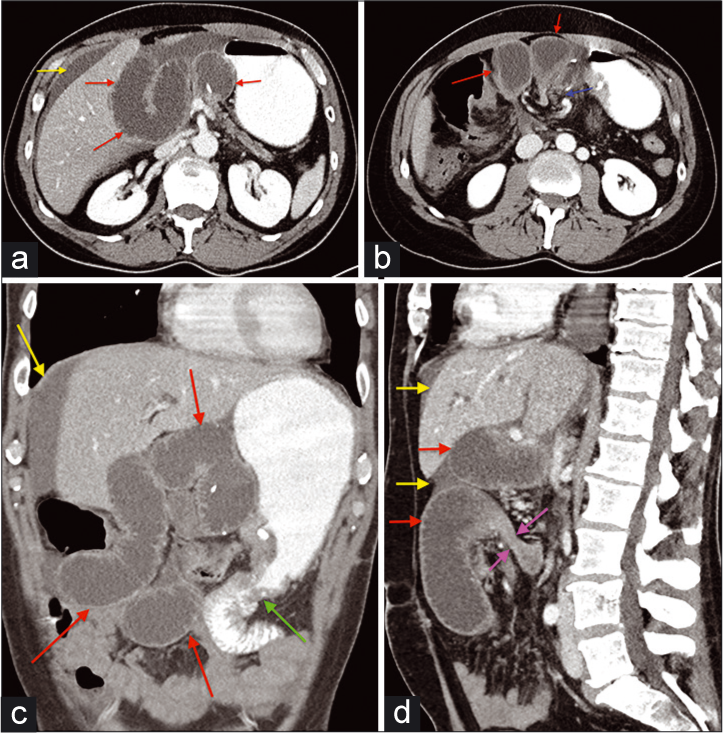

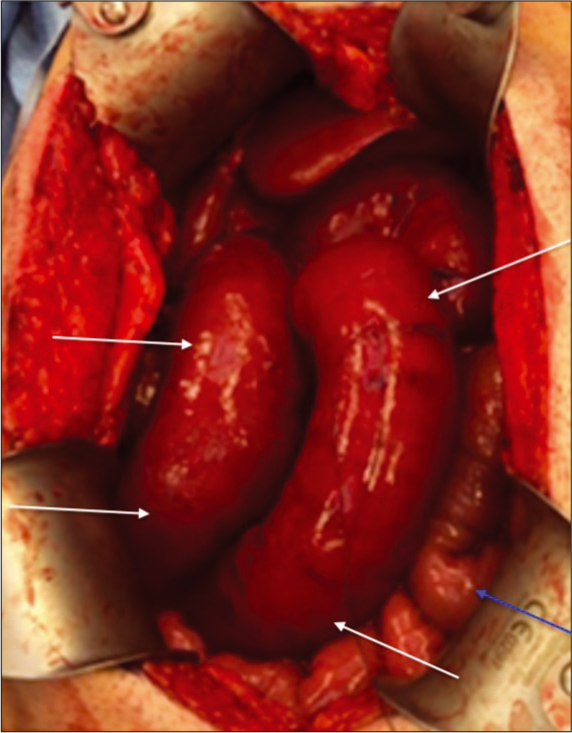

Six weeks following the surgery, the patient developed umbilical abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, with repetitive dry heaving. The pain was described as moderate-to-severe, exacerbated by palpation, and not alleviated by any factors. The patient had a normal bowel movement earlier that day and denied having a fever. Physical examination showed moderate distress with mild abdominal distention and hypoactive bowel sounds. Periumbilical and epigastric tenderness was present with minimal voluntary guarding, without rebound tenderness. Laboratory values demonstrated elevated liver enzymes (ALT of 144 U/L), hyperbilirubinemia (2.8 mg/dL then 5.1 mg/dL), and leukocytosis (18.7 × 109/L). A STAT CT abdomen/pelvis demonstrated post-Whipple anatomy, but with distension of the afferent pancreaticobiliary limb, measuring up to 4.7 cm [Figure 2]. A transition point was present in the upper mid abdomen, proximal to the jejunojejunostomy. The combined clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings were all consistent with ALS. There was also a “swirl” or abnormal rotation of the superior mesenteric vasculature, with poor opacification of the vein indicating compression with slow flow or thrombus. There was interloop fluid with mesenteric edema, but without pneumatosis or pneumoperitoneum. General surgery was consulted and recommended an urgent exploratory laparotomy with possible bowel resection. Exploration revealed a segment of dilated dusky small bowel [Figure 3] corresponding to the afferent pancreaticobiliary limb. The limb was found to have herniated through a defect in the transverse colon mesentery, and subsequently became obstructed. The degree of engorgement and dilation precluded manual reduction. Given this, approximately 15 cm of the limb was resected. Drainage of the afferent limb was re-established through a side-to-side Roux-en-Y anastomosis approximately 60 cm distal to the gastrojejunostomy.

- A 40-year-old male presented with jaundice, dark urine, pruritus, and a 20 lb unintended weight loss. The patient underwent a Whipple procedure for pancreatic cancer, recovered well, and presented 6 weeks later with moderate-severe pain, nausea, vomiting, and repetitive dry heaving. (a and b) Axial CT images with IV and oral contrast demonstrate dilation of the afferent loop (red arrow). Free intra-abdominal fluid is present (yellow arrow). There is twisting of the mesentery with poor opacification of the superior mesenteric vein (blue arrow) (c) Coronal CT image demonstrate dilation of the afferent loop (red arrow). Free fluid is again demonstrated (yellow arrow). The distal small bowel is normal. The gastrojejunostomy site is visualized (green arrow). (d) Sagittal CT image with IV and oral contrast demonstrates a transition point within the afferent loop distally (purple arrows). Dilation of the more proximal afferent loop is again seen (red arrow). Free fluid is present (yellow arrows).

- A 40-year-old male presented with jaundice, dark urine, pruritus, and a 20 lb unintended weight loss. The patient underwent a Whipple procedure for pancreatic cancer, recovered well, and presented 6 weeks later with moderato-severe pain, nausea, vomiting, and repetitive dry heaving. After CT findings compatible with afferent loop syndrome, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperative gross image demonstrates dilated, dusky, ischemic-appearing bowel (white arrows). This correlates with the CT findings and represented the afferent loop. An adjacent efferent loop (blue arrow) was normal in caliber.

DISCUSSION

While the traditional Whipple involves simply utilizing one jejunal segment to drain the gastric remnant, pancreatic remnant, and bile duct, a modernized approach has been to use the Roux technique to create two separate limbs. The so-called afferent limb drains pancreaticobiliary secretions,[3] whereas the efferent limb drains the gastric remnant. This dual-channel approach creates the potential scenario of an isolated obstruction of only the afferent limb, which will present clinically quite differently from a conventional bowel obstruction. Instead of dilated loops and air-fluid levels on a radiograph, usually there is a non-obstructive or non-specific bowel gas pattern. When contrast is administered fluoroscopically, the efferent limb remains non-obstructed, and transit time appears normal. It is only with cross-sectional imaging that the true pathology is revealed. Laboratory alternations can aid in the diagnosis, as stagnant biliary secretions will be reflected in a pattern consistent with cholestasis, as in this case. Whether the obstructive process is acute or chronic, potential complications include ischemia, perforation, peritonitis, ascending cholangitis, and pancreatitis.[4] If chronic, bacterial overgrowth may result in malnutrition, steatorrhea, and Vitamin B12 deficiency.[4] In acute

obstruction leading to ALS, the symptoms tend to be sudden with severe abdominal pain and vomiting, followed by abdominal tenderness and involuntary guarding.[5] Non-bilious emesis is typical, as the biliary and pancreatic secretions are sequestered within the obstructed the afferent loop.[5] CT is useful in predicting the cause before surgical intervention.[6] Expected findings include dilation of the afferent loop, which generally ranges between 3.3 and 5.8 cm.[7] The identification of a transition point may facilitate surgical management. Twisting of the mesentery can also indicate a component of volvulus or internal hernia. Focal wall thickening along the pancreaticojejunostomy can suggest local recurrence of malignancy while more diffuse wall thickening may suggest radiation enteritis. In cases of malignancy, carcinomatosis may be present at the level of obstruction. Given the infrequency of the complication, the literature on management of ALS post-Whipple is limited and derived from single-institution series.[8] A benign etiology of ALS generally results in definitive surgical intervention while palliative approaches may be undertaken in malignant etiologies.

CONCLUSION

Obtaining a CT exam and recognizing the characteristic findings of ALS can facilitate earlier diagnosis, predict the etiology before surgical intervention, and improve clinical outcomes.[6]

The case was anonymized, with exemption from IRB approval.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anastomotic technique influences outcomes after partial gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Am Surg. 2001;67:948-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT diagnosis of afferent loop syndrome. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:835-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1030-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enterolith causing afferent loop obstruction: A case report and literature review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:1091-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afferent loop obstruction after gastric cancer surgery: Helical CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28:624-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Using multidetector-row CT for the diagnosis of afferent loop syndrome following gastroenterostomy reconstruction. Yonsei Med J. 2011;52:574-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of afferent loop obstruction: Reoperation or endoscopic and percutaneous interventions? World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7:190-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]