Translate this page into:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Anal Region: Clinical Applications

*Corresponding author: Silvio Mazziotti, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Morphological and Functional Imaging, University of Messina, Messina, Italy. smazziotti@unime.it

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Cicero G, Ascenti G, Blandino A, Pallio S, Abate C, D’Angelo T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the anal region: Clinical applications. J Clin Imaging Sci 2020;10:76.

Abstract

Over the past years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become a cornerstone in evaluating anal canal and adjacent tissues due to its safeness, the three-dimensional and comprehensive approach, and the high soft-tissue resolution. Several diseases arising in the anal canal can be assessed through MRI performance, including congenital conditions, benign pathologies, and malignancies. Good knowledge of the normal anatomy and MRI technical protocols is, therefore, mandatory for appropriate anal pathology evaluation. Radiologists and clinicians should be familiar with the different clinical scenarios and the anatomy of the structures involved. This pictorial review presents an overview of the diseases affecting the anal canal and the surrounding structures evaluated with dedicated MRI protocol.

Keywords

Magnetic resonance imaging

Large bowel

Anal canal

INTRODUCTION

Anal canal diseases can be classified into benign and malignant.

Benign conditions include a wide range of pathologies, the most common of which are fistulas and abscesses.

The underlying cause of fistulization processes is unknown yet, although intramuscular glands’ infection with resultant intersphincteric or transphinteric spread is the most plausible hypothesis.[1-3]

Ultrasound (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are valuable tools for anal canal assessment.

The US is a safe technique that can currently rely on three different approaches for evaluating anal canal, transperineal, endovaginal, and endoanal; however, its performance strictly depends on the operator’s experience and it has a limited field of view.[4]

MRI has become a cornerstone in the evaluation of the anal canal and the adjacent structures as it provides a multiplanar assessment with high spatial resolution.[5]

Therefore, MRI offers additional elements for the patient’s clinical assessment and provides a “road map” for the surgeon to intervene when required.

This pictorial essay aims to present various diseases involving the anal canal and the surrounding structures assessed through MRI performance.

MRI GROSS ANATOMY AND TECHNIQUE

The anal canal is the most distal segment of the gastrointestinal tract, comprised between the rectum and the external surface.

It is surrounded by a double layer of sphincters involved in the defecatory process: The innermost comprises smooth involuntary muscular fibers. The outer is composed of a voluntary skeletal muscle.

MRI of the anal region is performed using a surface phased array coil, without needing intraluminal contrast agents or endocavitary coils.

Our protocol includes half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo (HASTE) with and without fat suppression (slice thickness: 3 mm; TR/TE ∞/80 ms; flip angle: 90°) obtained on standard sagittal, axial-oblique, and coronal-oblique planes; diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (DWI; slice thickness: 5 mm; b values: 0, 400, 800) obtained on standard axial or oblique-axial planes; ultrafast three-dimensional gradient echo T1-weighted with fat suppression (TR/TE: 5.7/1.8–4.0; flip angle: 15°) before and after injection of 0.2 mL/kg gadoterate of meglumine (Dotarem); and 30 mL of normal saline obtained on standard axial or oblique-axial planes.

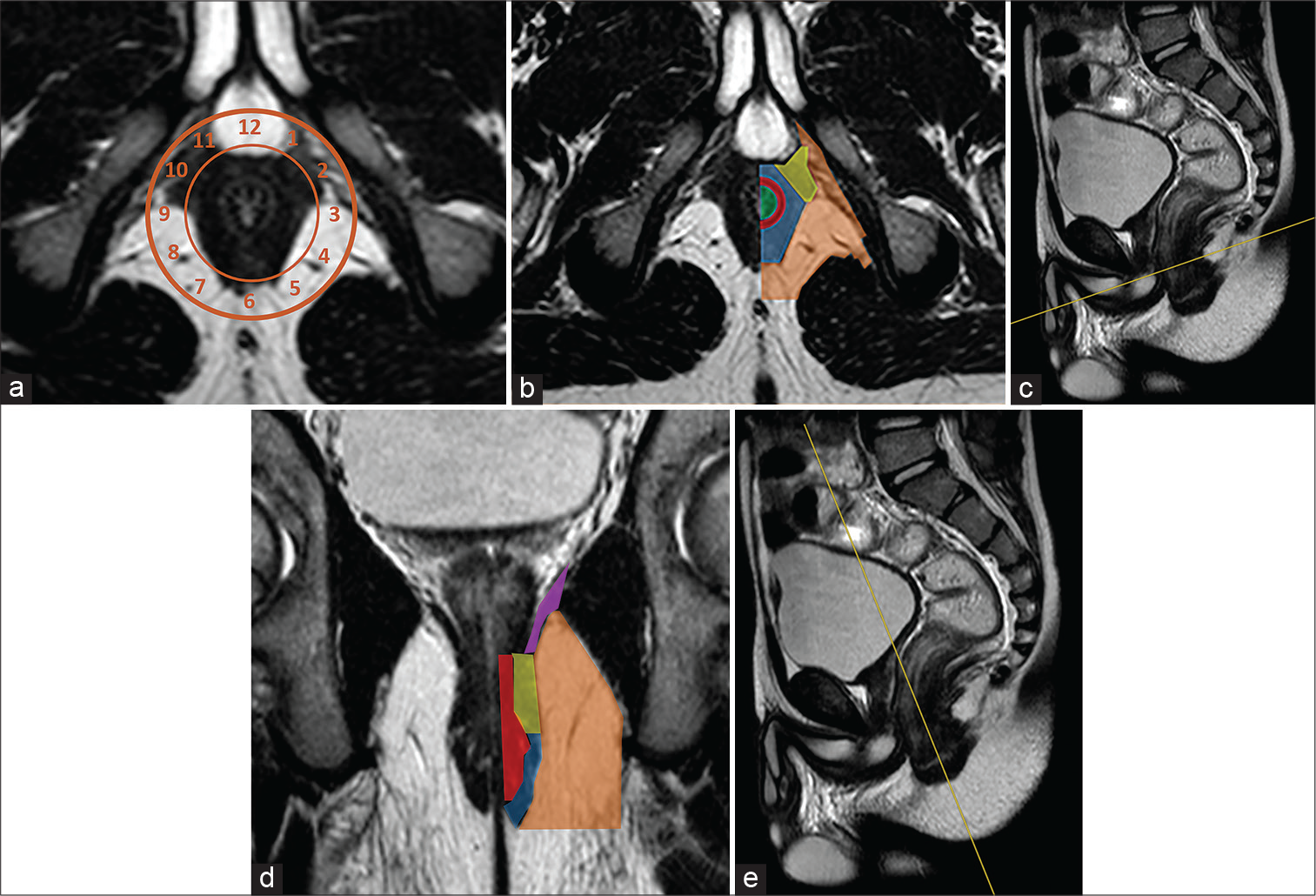

Coronal-oblique and axial-oblique planes are performed following the anal canal (parallel and perpendicular) [Figure 1].[1,3,5,6]

- Half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (haste T2-w) axial-oblique in a patient scanned in supine position (a) with clock benchmarks. The “anal clock” is a useful tool for reporting anorectal pathology. Anatomy of the anal region is showed on Haste T2-W axial-oblique scan (b), obtained perpendicularly to the anal canal long axis as showed on Haste T2-W sagittal reference scan (c), and coronal-oblique image (d), acquired in parallel with anal canal long axis as visible on sagittal Haste T2-W scan reference (e). Green area: Anal canal lumen; red line: Internal sphincter; blue area: External sphincter; yellow area: Puborectal muscle; purple line: Levator ani; orange area: Ischioanal fossa.

ANAL PATHOLOGY

Congenital

A broad spectrum of congenital pathologies can affect the anal region.[7]

Therefore, several attempts have been made for classifying anorectal malformations (ARMs), on the basis of their localization (high, intermediate, and low), gender prevalence (male and female), surgical management (approach and techniques), clinical outcomes, and coexistence with other simultaneous pathological conditions (syndromic and nonsyndromic).[8,9]

Clinical picture as well as imaging findings are critical to establish the proper medical treatment or to plan surgical intervention.

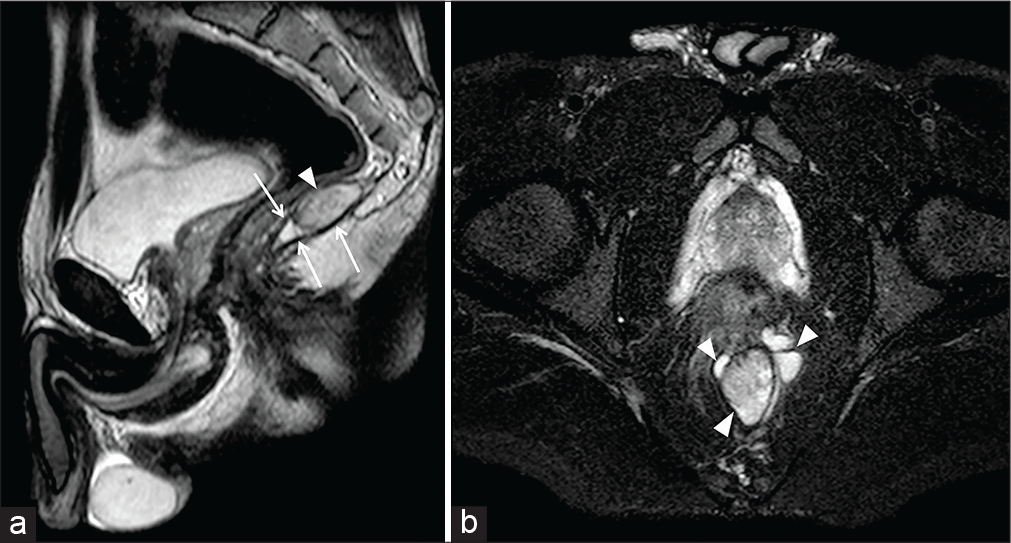

However, lesions arising from the anal canal and the adjacent tissues, when asymptomatic, can go unnoticed and may be detected as incidentalomas during adulthood [Figure 2].

- A 31-year-old male patient with constipation and defecatory discomfort. Sagittal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-w) (a) and axial-oblique Haste T2- with fat saturation (b) images show a multiloculated cystic mass (arrowheads) within the levator ani fibers (arrows), characterized by inhomogeneous hyperintensity. The finding is consistent with a “tailgut cyst,” a rare congenital malformation arising from the residual embryonic hindgut.

Benign

Benign pathology of the anal canal generally consists in fissures, fistulas, abscesses, and hemorrhoids. The related symptoms are typically non-specific, including pain, bleeding, cutaneous lumps, itching, and external drainage.[10]

Therefore, to reach a definitive diagnosis, physical examination is mandatory.

Radiological imaging is not recommended for hemorrhoid assessment, unless a further underlying cause of bleeding is suspected within the upper part of the colon.[11]

Due to the wide field of view, the high contrast and spatial resolution, MRI is capable in detecting mural alterations of the anal canal and extension to surrounding tissues. Limitations include the evaluation of the anal lumen, which is physiologically collapsed.

Fistulas and abscesses

Although often used as synonyms, the term “perianal fistula” refers to a chronic granulating tract connecting the anal canal and the cutaneous surface of perineum, “sinus tract” to a tunneling wound originating from the anal canal, extending into adjacent soft tissues, and ending in a blind “cul-de-sac,” “fissure in ano” to a linear ulcer confined within the anal canal, from the dentate line to the eternal margin.[12-14]

According to Parks’ classification, perianal fistulas can be classified, on the basis of their pathways and involvement of the sphincteric structures, into four types: Intersphincteric, transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, and extrasphincteric.[15] Fistolous tracts are visualized as linear hyperintensities on T2 weighted, DWI, and T1 weighted with fat saturation after gadolinium (Gd) injection sequences.[14]

Decrease in signal intensity can be related to fibrotic degeneration in long-standing diseases.

On the other hand, abscesses are inhomogeneous fluid collection, in which also small gas bubbles can be appreciated that can arise anywhere within the perianal tissues. They are generally typical of acute phases.

Pathologies that lead to a chronic inflammatory injury of anal structures represent an ideal substrate for the fistulization process to thrive.[1-3]

Therefore, perianal complications are frequently related to Crohn’s disease (CD) (up to 28% of CD patients) due to the transmural involvement and, tough more rarely, to ulcerative colitis 4% [Figure 3].[16]

- A 36-year-old female patient affected by ulcerative colitis (Mayo Stage II) complaining for vaginal pain and purulent drainage. Coronal-oblique half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-W) image (a) shows an intersphincteric fistula (arrowheads) within the right wall at the level of the third middle of the anal canal. The fistula extended anteroinferiorly to the right wall of the vagina, where an abscess (arrows) was detected on axial-oblique Haste T2- with fat saturation (b).

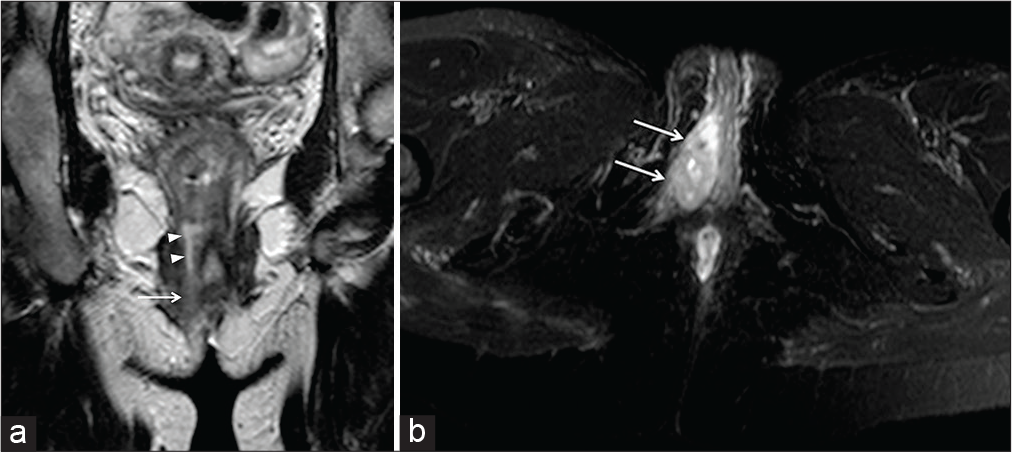

Anal canal affection in vasculitis, such as Behcet disease (BD), has also to be taken into account. In fact, a gastrointestinal localization has been recorded in up to 30% of BD patients. However, only a few cases of perianal involvement have been described so far [Figure 4].[17,18]

- A 19-year-old male patient was suffering from Behcet disease and uveitis. The patient complained about anal pain and purulent drainage at the level of the left gluteus cutaneous surface. Coronal-oblique half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-W) (a) and axial-oblique HASTE T2-W (b) with fat saturation show a fistulous tract (arrowheads) arising from the lower third of the anal canal.

In all the cases supramentioned, the goals of MRI consist in detecting the internal orifice within the anal canal, showing the fistulous route, with its caliber and extension, and the structures involved, to establish the most proper treatment.[12]

Malignant

Anal canal cancers are generally rare, accounting for 0.3% of all cancers and for 1.5–2% of the whole gastrointestinal malignancies.[19,20]

A strong correlation (approximately 90% of the cases) has been established with human papilloma virus (HPV), mainly HPV-16 subtype, and the human immunodeficiency virus.

Other risk factors include cervical dysplasia, autoimmune disorders and immune suppression in transplant recipients, cigarette smoking, and long-standing perianal fistulizing CD.[21]

According to their localization, they can be classified into “anal canal” and “anal margin” carcinomas. Anal canal tumors include three main types; squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which is the most common type (up to 80%), adenocarcinoma, which is rarer (10–20% of the cases) but more aggressive than SCC, and melanoma (1–4%).[22]

On the other hand, tumors of the anal margin consist on extramammary Paget’s disease, Bowen’s disease, anal margin SCC, basal cell carcinoma (0.2%), and melanoma (2–4%).[23]

Typical symptoms are pain, rectal bleeding, constipation, and mass sensation.

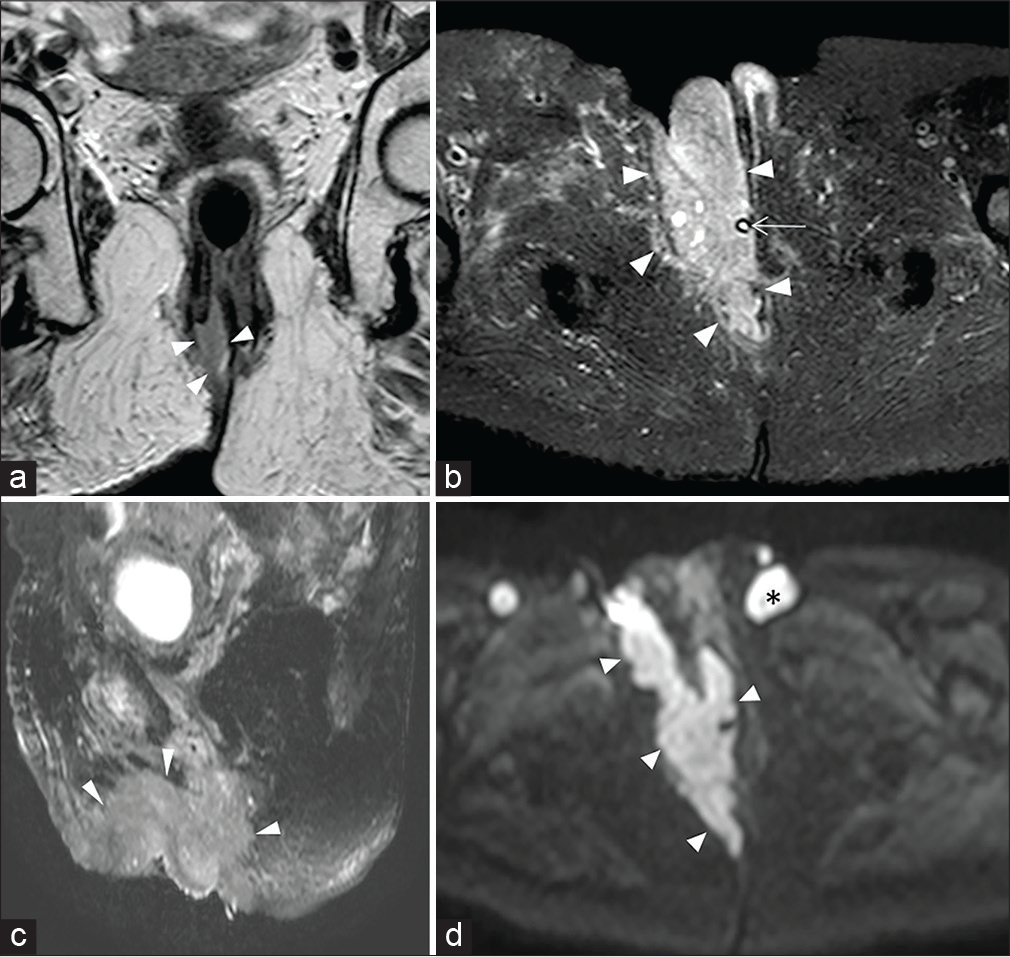

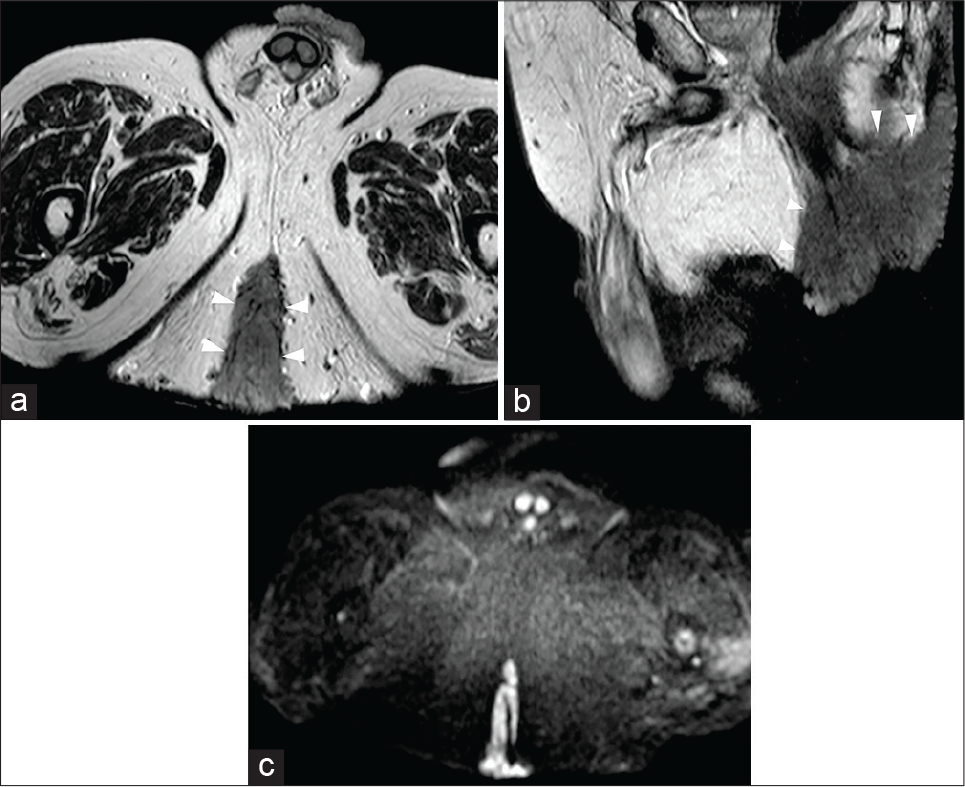

MRI is considered the imaging modality of choice for locoregional staging, providing information about dimensions, morphology, external extent, and metastatic lymph nodes [Figures 5 and 6].[19,20]

- A 76-year-old female patient with large squamous cell carcinoma anal cancer. Coronal T2-weighted image (a) shows the origin of the mass from the middle-lower third of the anal canal (arrowheads). T2-W SPAIR sequences obtained on axial (b) and sagittal (c) planes and axial diffusion-weighted imaging at b value of 800 s/mm2 (d) demonstrates the anterior extension with involvement of the right vaginal wall and ipsilateral clitoral body and labium majus (arrowheads). Asterisk: Lymphadenopathy. Arrow: Urinary catheter.

- A 69-year-old male patient was affected by giant condyloma acuminatum, a rare verrucosus slow growth tumor often associated with human papillomavirus infection. Axial-oblique (a) and sagittal (b) half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted scans show a hypointense large mass (arrowheads) involving the anal canal as well as the cutaneous surface and the surrounding fatty gluteal tissues. On axial-oblique diffusion-weighted imaging image (c), the mass is characterized by significant hyperintensity.

MRI features of anal cancer are not specific for a histological type or subtype and include iso- to hypointensity on T1-weighted scans and iso- to hyperintense on T2-weighted and DWI sequences. After Gd injection, the mass is generally characterized by an intense contrast enhancement.[20]

PERIANAL DISEASES

Perianal diseases include pathological conditions that originate from the tissues surrounding the anal canal.

Beyond rare and often benign tumors (i.e., lipomas or teratomas), the most frequent pathologies are associated with inflammation of the hair follicles.[24]

In these cases, differential diagnosis from perianal fistulas and abscesses is mandatory.

MRI takes advantage of its comprehensive overview of the tissues surrounding the anal canal: If a connection with the anal structures is not visible, perianal fistulas’ diagnosis can be excluded.

As well as for the other pathologies, MRI can provide an accurate assessment of treatment outcomes.

Pilonidal disease

Pilonidal disease is caused by an infection of hair follicles at the intergluteal cleft level, with the formation of sinus or abscess and external drainage of purulent material [Figure 7].[6,24]

- A 25-year-old male patient with swelling sensation at the higher level of the intergluteal cleft with occasional cutaneous fluid drainage. Sagittal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-w) (a) and axial-oblique HASTE T2-W with fat saturation (b) show a small oval-shaped hyperintensity (arrowhead) within the left side of the intergluteal cleft, adjacent to the cutaneous surface. The absent communication with the anal canal (arrow) allowed the diagnosis of pilonidal sinus.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa is caused by an obstruction of cutaneous hair follicular ducts located near to apocrine glands. The disease course is usually long term with frequent relapses and consists of abscesses and sinus tract formation.

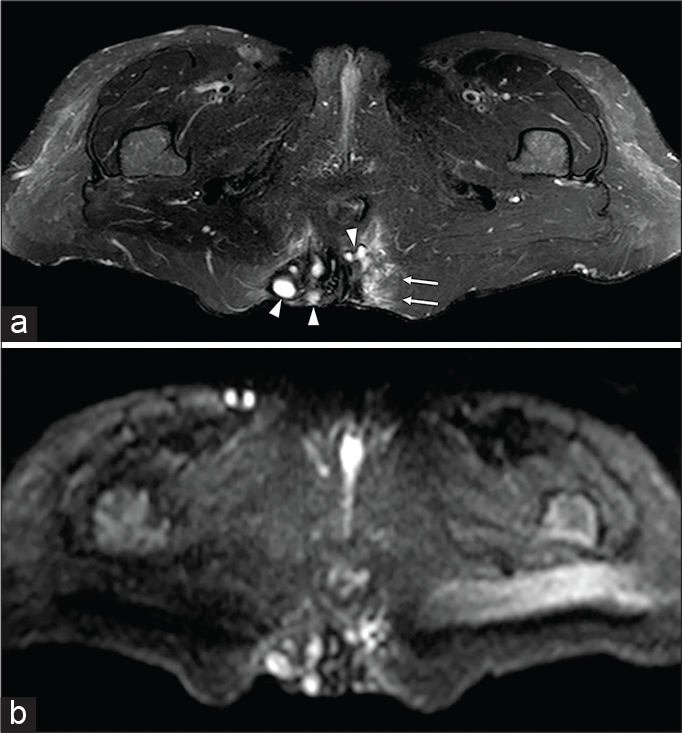

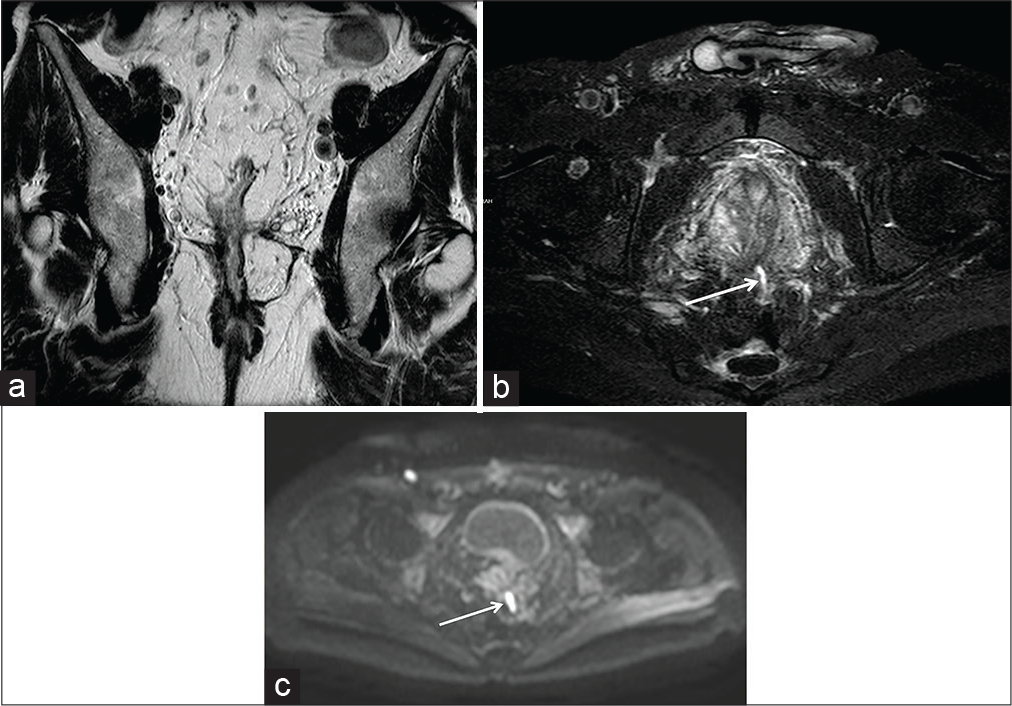

MRI typical features are linear- or nodular-shaped hyperintensities on T2-weighted sequences, usually with edema of the surrounding fat tissue [Figure 8].[6]

- A 47-year-old female patient complaining of a diffuse painful swelling of the buttocks with associated cutaneous lumps. On axial half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted with fat-saturation (a) and axial diffusion-weighted imaging (b) several rounds and oval-shaped small hyperintense collections (arrowheads), due to fluid purulent content, are detectable together with edema of the surrounding gluteal fat tissue (arrows). The distance from the anal canal confirmed the clinical suspicion of hidradenitis.

POST-TREATMENT EVALUATION

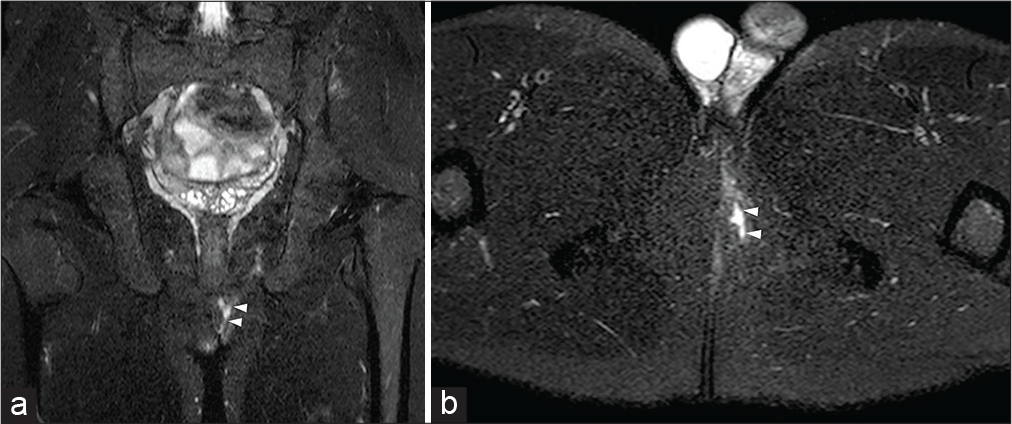

Chemoradiotherapy is usually the first-line treatment modality in anal cancer. When not sufficient in reaching complete regression, it can serve as a neoadjuvant approach before surgery [Figure 9].[25]

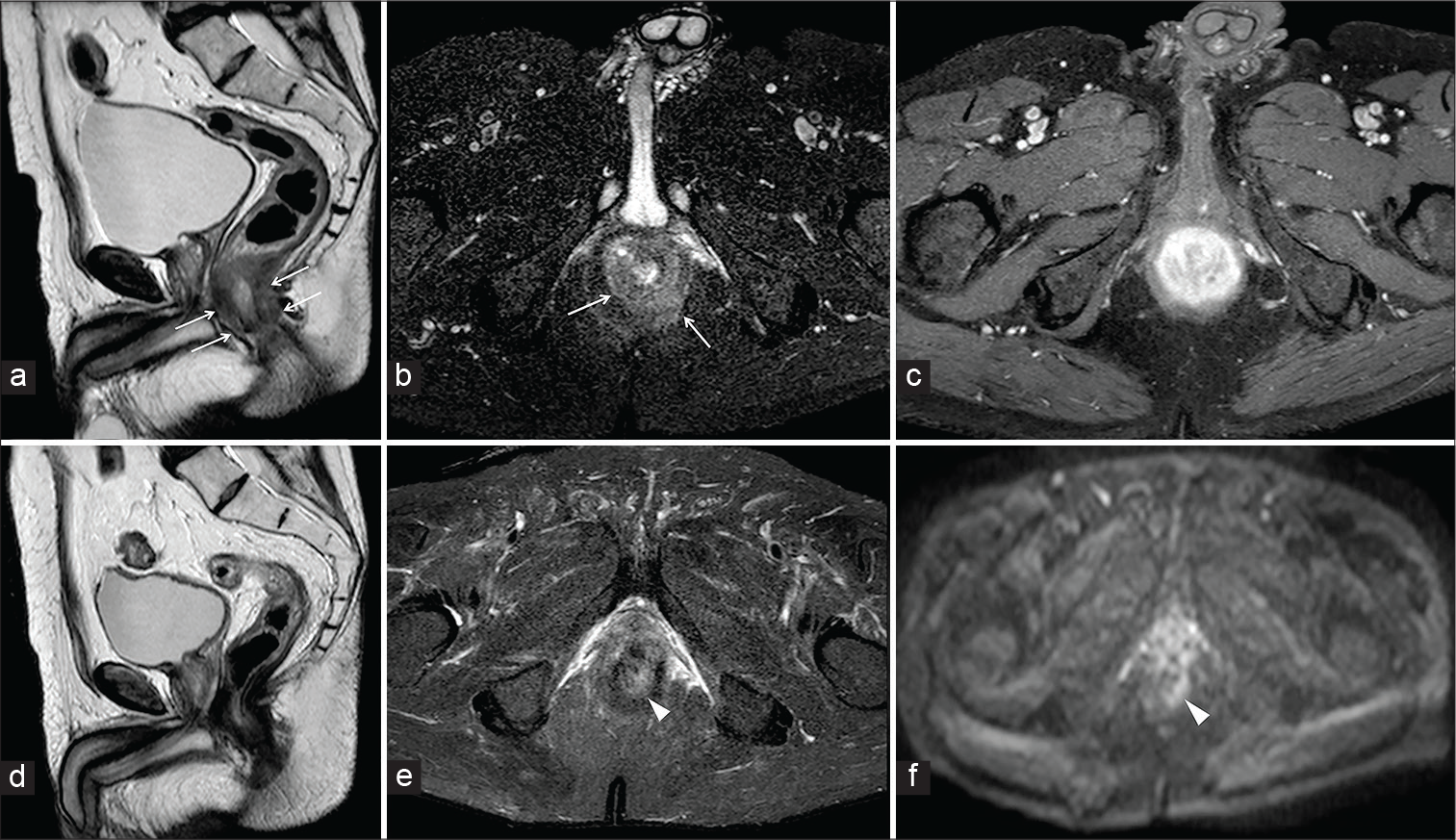

- A 63-year-old male patient affected by moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the anus. Sagittal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-W) (a) axial-oblique HASTE T2-W with fat saturation (b) demonstrates a concentric thickening of the anal walls (arrows), characterized by vivid enhancement on axial-oblique gradient echo T1-W with FS after gadolinium injection (c). The patient underwent chemotherapy and magnetic resonance imaging before the intervention. Sagittal HASTE T2-W (d) axial-oblique HASTE T2-W with FS (e) showed a significant reduction of the malignancy with residual thickening of the left posterior wall (arrowheads) confirmed by oblique-axial diffusion-weighted imaging (f).

MRI features of a positive response are decrease in size and signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences, due to fibrosis.

However, thickening or hyperintensity of the mucosa related to mucosal edema can be normal effects of chemoradiotherapy and should not be misinterpreted as residual tumor.[20]

Nevertheless, perianal MRI can help detect outcomes after colonic or pelvic surgery.[26]

Surgical repair of ARMs in newborns and children must be reassessed by MRI to determine the need of additional operations.[27,28]

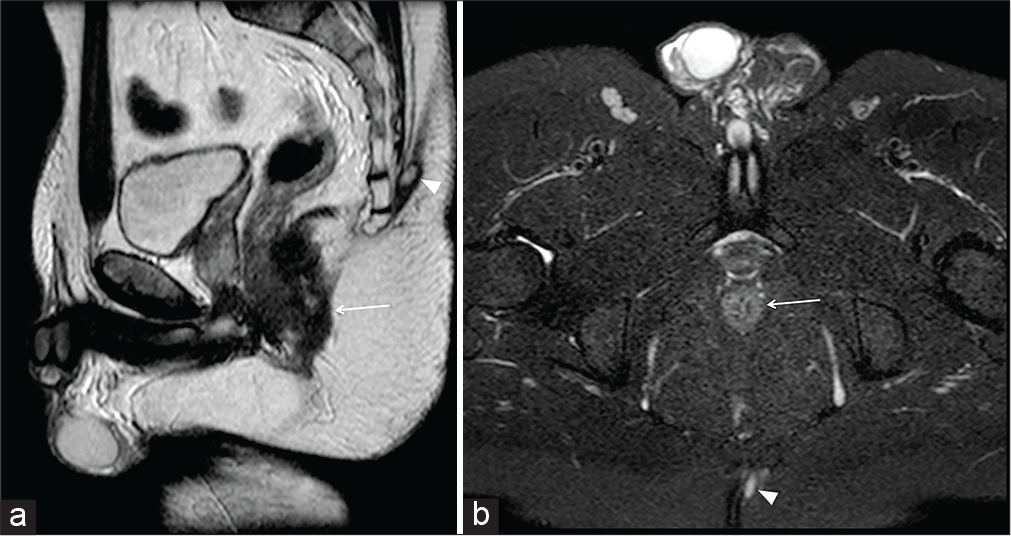

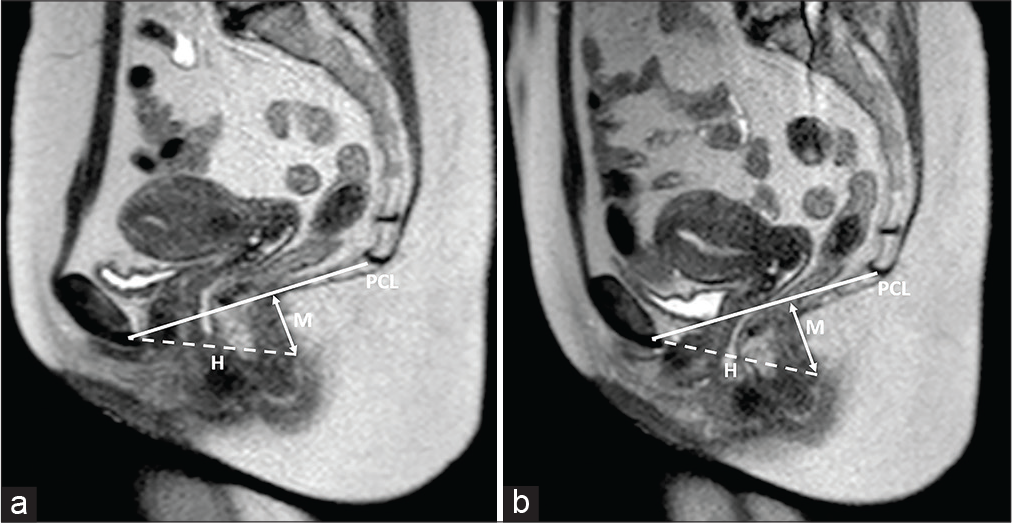

Furthermore, although CT scan and fluoroscopy can better detect the presence of dehiscence, MRI can rely on its higher soft-tissue resolution for detecting acute (i.e., fistulas/ abscess formation and urinary retention) or chronic (i.e., strictures/stenosis and fecal incontinence) complications [Figure 10 and 11]. Moreover, sequences obtained before and during Valsalva maneuver can additionally assess pelvic floor continence and visceral prolapses when the patient complains about defecatory dysfunctions (constipation or incontinency) [Figure 12].[29]

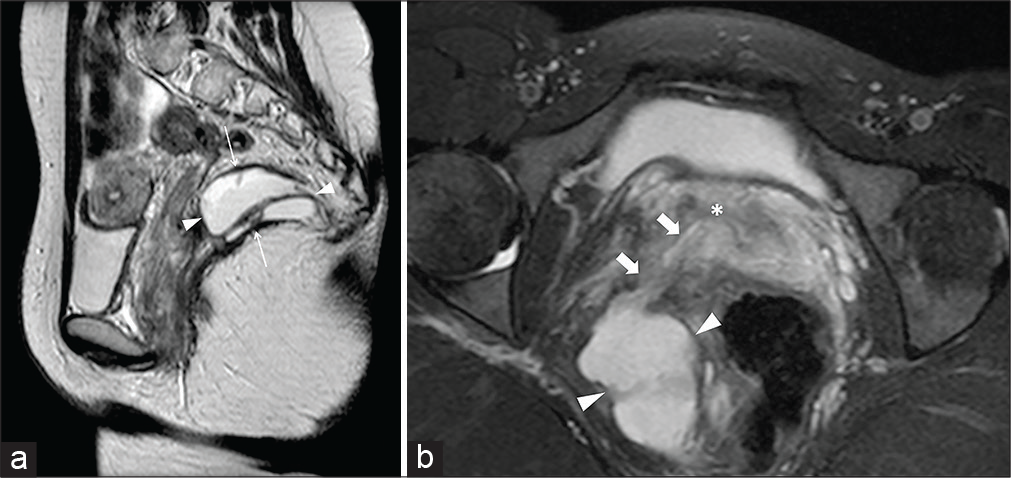

- A 24-year-old female patient suffering from abundant pus drainage through the vagina occurred after a pelvic intervention for deep endometriosis. Sagittal half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-W) image (a) shows a sizeable multiloculated abscess (arrowheads) located within the right levator ani (thin arrows). Axial-oblique HASTE T2-W with fat-saturation zoomed reconstruction (b) shows the fistulous communication (thick arrows) between the abscess and the vaginal lumen (asterisk).

- A 55-year-old male ulcerative colitis patient who underwent radical colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis surgery, appreciable on coronal-oblique half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo T2-weighted (HASTE T2-W) scan (a). At the time of magnetic resonance imaging, 16 years after the intervention, a small sinus tract (arrow) of the anterior wall of the pouch was detectable on axial-oblique HASTE T2-W with fat saturation (b) and axial diffusion-weighted imaging (c) scans.

- A 41-year-old female patient was suffering from chronic constipation, hemorrhoids, and internal prolapse of rectal mucosa. Sagittal T2-weighted half-Fourier acquisition single-shot turbo-spin-echo sequences obtained at rest (a) and during the Valsalva maneuver (b). Visceral prolapse and pelvic floor relaxation degree can be assessed through the assessment of three lines: the pubococcygeal (PCL; continuous line), drawn from the last coccygeal joint to the inferior border of the pubic symphysis; the “H-line” or “levator hiatus width” (dash line), drawn from the pubis to the posterior wall of the anorectal junction; and the “M-line” or “muscular pelvic floor relaxation line” (arrowed line), which is perpendicular to the pubococcygeal and reaches the posterior wall of the anorectal junction. Typically, the H and M lines should not exceed 5 cm and 2 cm in length. In the case presented, while the “H-line” did not modify between the two sequences, the “M-line” was measured 2.6 cm at rest and 3.8 cm during Valsalva maneuver performance.

CONCLUSION

The anal canal and the adjacent structures can be involved in different clinical conditions.

Perianal MRI is an imaging tool that requires a specific technical approach; it is provided with high soft-tissue resolution and offers a complete overview of anal and perianal structures.

Radiologists and clinicians should be familiar with this technique’s capabilities in different clinical scenarios.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- MRI of perianal fistulae: A pictorial kaleidoscope. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:1451-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of magnetic resonance imaging in evaluation of the activity of perianal Crohn's disease. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:616-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging evaluation of perianal fistulas: Spectrum of imaging features. Radiographics. 2012;32:175-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound imaging of the anal sphincter complex: A review. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:865-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rectal imaging: Part 2, perianal fistula evaluation on pelvic MRI-what the radiologist needs to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W43-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MRI evaluation of anal and perianal diseases. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2019;25:21-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congenital perianal lipoma: A case report and review of the literature. Surg Case Rep. 2019;5:199.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anorectal malformations. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2015;20:10-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benign anorectal disease: An update on diagnosis and management. JAAPA. 2006;19:28-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of fistulae and sinus tracts in patients with Crohn disease: Value of MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:999-1003.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perianal disease in patients with ulcerative colitis: A case-control study. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:338-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intestinal behcet's disease with perianal abscess and necrosis: A case report. Visc Med. 2007;23:199-201.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Similarities and differences between Behçet's disease and Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:228-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumors and tumorlike conditions of the anal canal and perianal region: MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2016;36:1339-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of anal carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W335-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cancer of the anal canal: Diagnosis, staging and follow-up with MRI. Korean J Radiol. 2017;18:946-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neoplasms of anal canal and perianal skin. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:54-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging features of benign perianal lesions. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019;63:617-23.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in the management of anal cancer. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000. Faculty Rev-1572

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Complications following anorectal surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2016;29:14-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postoperative pelvic MRI of anorectal malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1469-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation after anorectal pull-through surgery for anorectal malformations: A comprehensive review. Pol J Radiol. 2018;83:e348-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dynamic MR imaging of the pelvic floor: A pictorial review. Radiographics. 2009;29:e35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]