Translate this page into:

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm of the Liver Masquerading as an Echinococcal Cyst: Radiologic-pathologic Differential of Complex Cystic Liver Lesions

Address for correspondence: Dr. Daniel Jeong, Department of Radiology, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, 12902 USF Magnolia Drive, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. E-mail: daniel.jeong@moffitt.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Although simple liver cysts are common, complex cystic liver lesions are infrequent and represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. The differential diagnosis of complex cystic liver lesions can be grouped into neoplastic, infectious or inflammatory, and miscellaneous pathologic entities. Clinicians should remember to consider mucinous cystic neoplasm and echinococcal cysts in the differential, which are uncommon etiologies for liver lesions but may expose unique challenges. We present a case of a 49-year-old female who was referred for evaluation of a new complex cystic liver lesion. The following brief review describes how radiologic imaging and pathologic testing can help distinguish between the broad spectrum of diseases that may produce cystic liver lesions.

Keywords

Cystic liver lesion

echinococcal cyst

mucinous cystic neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Complex cystic liver lesions can present a diagnostic challenge. Although these lesions represent a heterogeneous group of disorders, they can have similar clinical manifestations. The differential diagnosis of complex cystic liver lesions can be grouped into neoplastic, infectious or inflammatory, and miscellaneous pathologic entities.[1] Clinicians should remember to consider mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) and echinococcal cysts in the differential, which are uncommon etiologies for liver lesions but may expose unique challenges. We present a case of a 49-year-old female who presented for evaluation of a new complex cystic liver lesion. The following brief review describes how radiologic imaging and pathologic testing can help distinguish between the broad spectrum of diseases that may produce cystic liver lesions.

A 49-year-old female with no significant past medical history was referred for evaluation of a new liver lesion found during evaluation of abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea. Examination was noncontributory and laboratory testing revealed normal liver function tests, elevated alpha-fetoprotein (10 ng/ml) (normal 0–8.3 ng/ml), and elevated cancer antigen CA19-9 (328 μ/ml) (normal 0–35 μ/ml).

RADIOLOGIC FEATURES

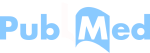

Computed tomography (CT) showed a 10.2 cm × 9.2 cm × 10.1 cm heterogeneous multiloculated right hepatic cystic lesion with several calcifications along septae [Figure 1a]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [Figure 1b and c] demonstrated multiple loculated simple cystic and proteinaceous components within the nonenhancing mass [Figure 1d]. Based on the radiologic findings, the differential diagnosis included echinococcal cyst and MCN; therefore, echinococcal antibody was subsequently tested and found to be negative. Given the elevated tumor markers and concerning imaging findings, therapeutic right hepatectomy was performed, and the patient had an uneventful postoperative recovery with resolution of symptoms.

- 49-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea found to have a mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver. (a) Contrast-enhanced axial computed tomography image demonstrates a multiloculated cystic right hepatic mass (arrows) with focal calcification along an internal septum (open arrow). Magnetic resonance imaging (b) T1-weighted and (c) T2-weighted images demonstrate multiple well-defined cystic loculations with different T1 and T2 characteristics based on proteinaceous content. Peripheral high T1 and low T2 signal represents highly proteinaceous content (X), whereas low T1 and high T2 signal represents simple fluid (*). (d) Intraoperative ultrasound image of the liver demonstrates the corresponding relatively hypoechoic simple fluid component of the lesion (*) with echogenic deeper complex cystic components (X).

On CT, MCN appears as a complex hepatic cyst typically with irregular cystic walls and possible loculations and septae. Septae in MCN are thin and smooth in contour and may enhance with intravenous contrast. Calcifications, papillary projections, and small mural nodules (<1 cm) may also be present. Attenuation of each cystic loculation depends on proteinaceous content and can vary from simple fluid to mildly hyperdense fluid.

MRI can show varying T1- and T2-weighted signal within loculations depending on the proteinaceous content of fluid. Septa are well delineated on MR, and septal or mural calcifications will have low T1- and T2-weighted signals. Thin internal septae may enhance, however nodular enhancement or enhancement of irregular thickened walls raise suspicion of malignant transformation. While MR may offer the most specific evaluation of complex cystic liver masses, CT can better delineate degree of mural or septal calcifications.

On ultrasound, MCN has a well-defined multiloculated, anechoic or hypoechoic appearance. Septa are echogenic and may be vascular on color Doppler imaging. Calcifications, mild mural/septal nodularity, or papillary projections can also be appreciated on ultrasound. Internal echoes or layering debris may be present within complex fluid components. When a suspected MCN is initially identified on ultrasound, a contrast-enhanced MR or CT may be helpful for confirmation.

PATHOLOGIC FEATURES

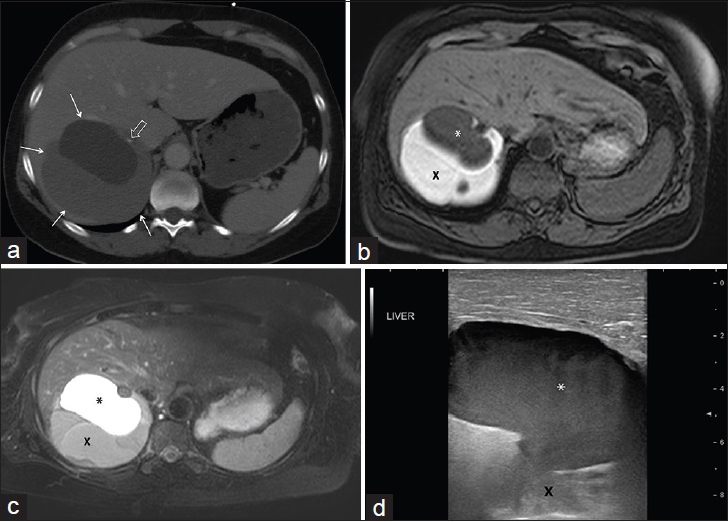

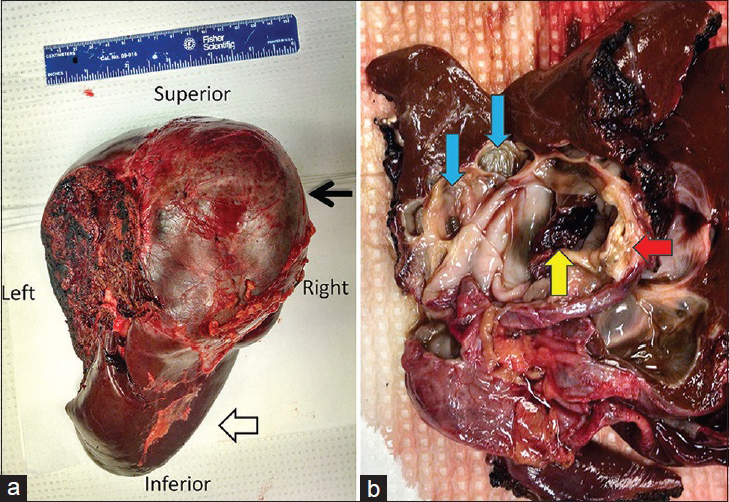

Gross images of the surgically resected mass demonstrated a completely excised encapsulated cystic mass [Figure 2a] with loculated components, mural nodules, calcifications, and intraluminal debris [Figure 2b]. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections [Figure 3a and b] showed a single layer of bland, cuboidal to low columnar mucinous epithelium lining cystic space; the mucinous epithelium showed no high-grade dysplasia or malignancy. Mild benign degenerative changes were also present. The underlying stroma was composed of densely packed spindle cells with occasional histiocytes, histologically mimicking ovarian-type stroma. Immunohistochemistry performed on the lesion [Figure 3c and d] showed characteristic nuclear labeling by estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) in the stromal spindle cells. The morphological and immunophenotypical features were consistent with the diagnosis of MCN according to the World Health Organization 2010 classification.

- 49-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea found to have a mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver. Gross specimen images of a resected mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver in the same patient. (a) Posterior view of the resected right hepatectomy specimen. The left margin of the specimen delineates the transection plane. The image shows encapsulated multiloculated cystic mass (black arrow) and healthy surrounding liver (open arrow). (b) Gross image of the transected specimen reveals the inner surfaces and contours of mass. The mass demonstrates multiple loculated components (blue arrows), intracystic debris (yellow arrow), and mural nodules with calcifications (red arrow).

- 49-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea found to have a mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver. Histology and immunohistochemistry images from the hepatic mucinous cystic neoplasm surgical specimen. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin stained sample at 2x magnification shows irregular cystic spaces lined by a single layer of mucinous epithelium (black arrows) with underlying dense cellular stroma (white circles). No necrosis or features associated with malignancy were seen. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin stained sample at 20x magnification shows bland columnar mucinous epithelial cells (black arrows) and the adjacent ovarian stroma-like mesenchymal component composed of densely arranged spindle and fibroblastic-like cells (white circles). No cellular atypia, no cellular overlapping, no mitoses, and no nuclear pleomorphism were identified; no morphological evidence suggestive of malignancy was seen. (c) Immunohistochemistry test for estrogen receptor, 20x magnification shows the stromal cell nuclei highlighted by estrogen receptor staining (arrows). (d) Immunohistochemistry test for progestrogen receptor, 20x magnification shows the stromal cell nuclei highlighted by progesterone receptor staining (arrows).

The pathological evaluation of an MCN includes defining histological grade of lining epithelium, tumor cell morphology, and atypia, identification of ovarian type stroma, involvement of adjacent bile ducts, and presence or absence of any malignant or invasive component.[23] MCNs need to be distinguished from other cystic lesions in hepatobiliary system including solitary biliary simple cysts, intraductal papillary neoplasms, and cystic hamartomas.

Histopathologically, MCN is characterized by mucus-secreting cuboidal or columnar epithelial cells and a layer of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells supported by distinctive stroma resembling ovarian tissue.[23] Positive ER and PR detection in stromal cell nuclei has fueled speculation that sex-related hormones play an important role in the pathogenesis of MCN.[4] In addition, inhibin is also positive in these ovarian type stromal cells. In practice, ER, PR, and inhibin are the main pathologic markers required for confirming a diagnosis of MCN.

Malignant transformation of MCN to biliary cystadenocarcinoma is determined by cytopathology by features including a multilayered epithelium, frequent mitotic figures, loss of polarity, nuclear pleomorphism, as well as an invasive component.[3] Both MCN and biliary cystadenocarcinoma express reactivity to cytokeratins, carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and CA 19-9 as seen in our patient.[3]

DISCUSSION

Cystic liver lesions are common and may represent a myriad of disorders in adults. Most cysts are found incidentally on imaging and follow a benign course. Liver cysts may first be distinguished as simple or complex lesions. Simple hepatic cysts appear as fluid-filled structures with smooth thin walls, whereas complex liver cysts have additional elements including wall thickening or irregularity, septations, internal nodularity, enhancement, calcification, or hemorrhagic/proteinaceous contents.[1] Solitary simple liver cysts are typically asymptomatic and rarely require treatment, while numerous simple liver cysts may be related to autosomal dominant polycystic disease. While either CT or MRI can confidently diagnose benign simple cysts, MRI is often needed to fully evaluate complex cystic lesions.

The differential diagnosis for complex cystic liver lesions varies from neoplastic to infectious or inflammatory etiologies to miscellaneous pathologic entities. Among neoplastic etiologies, metastatic disease from the ovaries, colon, and some neuroendocrine tumors may occasionally appear as cystic liver lesions. Cystic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and giant cavernous hemangioma are primary hepatic neoplasms with hypervascularity leading to cystic degeneration.[4] MRI shows iso- to mildly hyper-intense T2-weighted signal, peripheral enhancement, and associated restricted diffusion in cystic metastases. HCC with hemorrhagic or necrotic components can also appear cystic on imaging. Irregular mural nodularity, however, demonstrates classic HCC arterial enhancement with delayed washout, and this feature is helpful in distinguishing cystic HCC from other entities.[4]

MCN of the liver, as presented in our case report, is a rare tumor previously known as biliary cystadenoma. According to the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification, hepatic MCNs are defined as a cyst-forming epithelial neoplasm, with mucin-producing epithelium, and ovarian-type subepithelial stroma, usually without bile duct communication.[5] Predominantly found in middle-age females and more often found in the right hepatic lobe than left, MCN can transform into malignant biliary cystadenocarcinoma and resection is recommended.[2]

Infectious causes of complex cystic liver lesions usually relate to abscesses from bacteria or fungi, but amebae and echinococcal cysts are important to exclude before attempted surgical resection or drainage. Common organisms producing pyogenic or fungal abscesses include Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Candida species in immunocompromised hosts, and clinical history with serologic testing can often pinpoint the diagnosis.[1] Similarly, clinical history can aid in the diagnosis of amebic liver abscesses, which are important to exclude because they rarely necessitate therapeutic drainage.[1] On imaging, hepatic abscesses show peripheral and septal enhancement with central necrosis. Central gas is seen in < 20% of cases. Sites of disease are related to the origin of infection with biliary tract pathologies presenting as multiple small abscesses in both lobes, whereas portal pathology presents with solitary larger lesions more common in the right hepatic lobe. Penetrating trauma or iatrogenic infection also present with solitary larger abscesses.

Echinococcal cysts are also important to exclude before attempts at invasive procedures since intraprocedural leakage of antigen-laden echinococcal fluid into circulation can lead to anaphylactic shock.[46] Echinococcal cysts, also known as hydatid cysts, are caused by the parasite Echinococcus granulosus.[7] On imaging, echinococcal cysts frequently present as a higher density mother cyst containing peripheral lower density daughter cysts on CT with mixed signal on magnetic resonance depending on the proteinaceous debris content.[4] Echinococcal cysts tend to be smaller in size, more homogeneous, and without papillary projections compared with MCN.[6] On pathological examination, echinococcal cysts are composed of three layers: An inner germinal layer, middle laminated membrane, and an outer pericyst of fibrous strands and connective tissue enveloped by host parenchymal cells.[7] Serum echinococcal antibody and tumor markers can aid in the differentiation although sensitivity is not 100%.[8] Immunoblot and ELISA assays are also helpful in identifying echinococcal cysts.[6]

Miscellaneous pathologic entities that may produce complex cystic liver lesions include posttraumatic and hemorrhagic complications. Hepatic hematomas or infarction, bilomas, or hemorrhagic cysts may occur following trauma and appear as complex liver lesions. Hepatic extrapancreatic pseudocysts may be difficult to distinguish from other complex liver lesions though imaging findings consistent with associated pancreatitis can often aid in diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

Although simple liver cysts are extremely common, large solitary and complex cystic liver lesions are uncommon and represent a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. The differential diagnosis should include MCNs given the potential for malignant transformation, and unique challenges such as anaphylactic shock due to echinococcal cysts must also be taken into consideration. History, laboratory testing and histopathology, and radiologic imaging can help narrow the diagnosis and guide treatment planning. Attentiveness to the broad differential diagnosis of complex cystic liver lesions will help clinicians decide on appropriate diagnostic testing and treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2016/6/1/12/179426

REFERENCES

- Prolapse into the bile duct and expansive growth is characteristic behavior of mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:148-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cystic neoplasms of the liver: Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:119-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of multilocular cystic hepatic lesions: CT and MR imaging findings with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2013;33:1419-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver. In: Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system (4th ed). Lyon: IARC Press; 2010. p. :236-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multiloculated cystic liver lesions: Radiologic-pathologic differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 1997;17:219-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pericyst: The outermost layer of hydatid cyst. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1377-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the liver: Mimicker of echinococcal cyst. J Surg Case Rep 2012 2012 5

- [Google Scholar]