Translate this page into:

Volumetric and Shape Analysis of the Subcortical Regions in Schizophrenia Patients: A Pilot Study

Address for correspondence: Dr. Shahid Bashir, Neuroscience Center, King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam, Dammam, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: sbashir10@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

Investigation of brain structure in disease has been enhanced by developments in shape analysis methods that can identify subtle regional surface distortions. High-resolution magnetic resonance (MR) imaging was used to compare volumetric and shape analysis in schizophrenia (SCZ) patients and healthy controls (CON).

Methods:

T1-weighted, 1-mm thick MR images were acquired for 15 patients with SCZ and 15 age-matched healthy controls using subcortical volume and shape analysis, which we believe to be complimentary to volumetric measures.

Results:

SCZ patients showed significant shape differences compared to healthy controls in the right hippocampus (P < 0.005), left and right putamen (P < 0.044 and P < 0.031), left caudate (P < 0.029), right pallidum (P < 0.019), and left thalamus (P < 0.033).

Conclusion:

Our results provide evidence for subcortical neuroanatomical changes in patients with SCZ. Hence, shape analysis may aid in the identification of structural biomarkers for identifying individuals of SCZ.

Keywords

Brain structure

high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging

schizophrenia

shape analysis

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia (SCZ), a highly incapacitating complex disorder affecting about 1% of the general population, is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.[12] Individuals with SCZ show significant brain morphological abnormalities, but there is considerable heterogeneity in the effect sizes and patterns of brain differences across studies.[34] The study of structural brain abnormalities in SCZ can help us understand its causes, progression, and even treatment effects.

Volumetric analyses of structural brain imaging data have been a mainstay of brain structure investigations in psychiatry.[56] The complement data resultant from volumetric and shape analysis methodology have been shown to identify group abnormalities in psychiatry disease.[789] Since shape analysis methods specifically identify impaired pathways, where the volumetric analysis did not show the surface abnormalities within the brain supports the revealing of localized deformations more on the surface of a brain structure.[15610] This is particularly important in the study of brain structures with explicit regional differentiation in function, such as the thalamus or striatum.[1112] Few studies have shown the shape analyses for SCZ.[16791013]

In the current study, we investigated the volumes and shapes of subcortical structures (i.e., the hippocampus, amygdala, caudate, putamen, globus pallidus, nucleus accumbens, and thalamus). We hypothesize that structural abnormalities will exist with SCZ. Abnormalities are expected to be largely trend toward shrinkage and be best captured by shape analysis.

METHODS

Participants

Participant groups included as follows: SCZ (n = 15) and healthy controls (CON) (n = 15) with ages ranged between 33.14 ± 9.96 (mean ± standard deviation) years. Participants were enrolled through the local psychiatric clinics, at King Saud University Hospital, whereas the control group were recruited through the health recruitment system. All participants gave written informed consent for participation and study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of King Khalid University Hospital. SCZ and CON participants were all outpatients, and clinically stable for at least 2 weeks.

Participants were excluded if they: (a) met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria for substance dependence or severe/moderate abuse during the prior 6 months; (b) had a clinically unstable or severe general medical disorder; or (c) had a history of head injury with documented neurological sequelae or loss of consciousness.

Table 1 shows the demographic data of participants.

| Parameters | Control (n=15) | Schizophrenia (n=15) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.8±8.9 | 33.9±9.9 |

| Height | 170±7.1 | 154±45 |

| Weight | 74±15 | 77±29 |

Vales are presented in Mean±SD

Clinical assessment

They were diagnosed by a consensus between a research psychiatrist and a trained research assistant who used the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms was used to assess the psychopathology. Specific subscale scores were summed to develop to measures of positive symptoms (i.e., hallucination and delusion subscales), disorganization (i.e., formal thought disorder, bizarre behavior, and attention subscales), and negative symptoms (i.e., flat affect, alogia, anhedonia, and amotivation subscales).

Image acquisition

A Siemens Magnetom Verio 3T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) clinical scanner (Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Erlangen, Germany) and 12-channel phased-array head coil were used to acquire: (1) T1-weighted three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo imaging: Repetition time (TR) = 1600 ms, echo time (TE) =2.19 ms, inversion time = 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, acquisition plane = sagittal, voxel size = 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm, field-of-view (FOV) = 256 mm, acquired matrix = 256 × 256, acceleration factor (iPAT) =2; (2) Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery : TR = 9000 ms, TE = 128 ms, inversion time = 2500 ms, flip angle = 150°, acquisition plane = axial, slice thickness = 5 mm, FOV = 220 mm, acquired matrix = 256 × 196, acceleration factor (iPAT) =2.

Data analyses

Shape of subcortical regions

Segmentation of subcortical regions

The anatomical T1 data (DICOM format) of each subject was converted into compressed NIfTI format using MRIcron (https://www. nitrc.org/projects/mricron). Using FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FIRST Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom), the following tools were applied sequentially: brain extraction by the BET tool (Smith, 2002) to clear noncerebral voxels; automated segmentation by the FIRST tool of the subcortical regions.[1415] Voxel-based thresholding, corrected, for multiple comparisons was adopted. The significance level with the family-wise error corrected was set at P = 0.05 Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (for MAC, Rel 20.0. 2016. SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Group comparisons of fractal dimensions (FD) were performed using Student's independent t-test.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic profile of the sample is shown in Table 1.

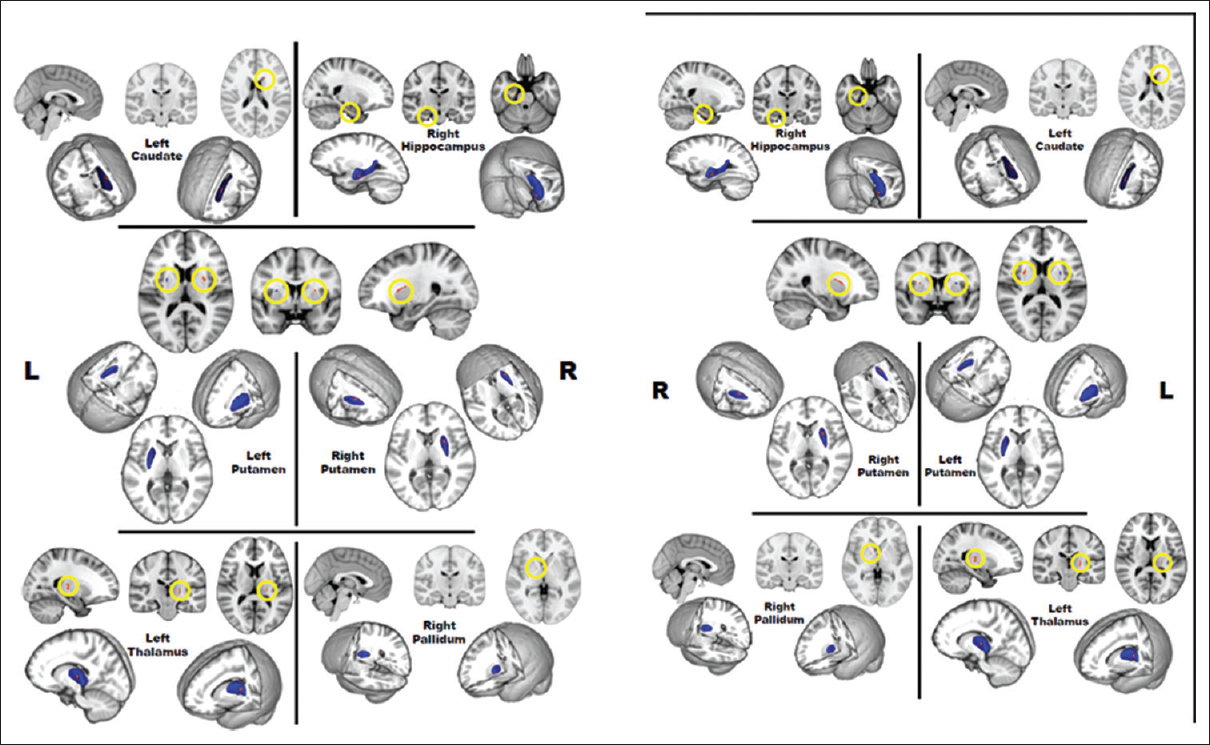

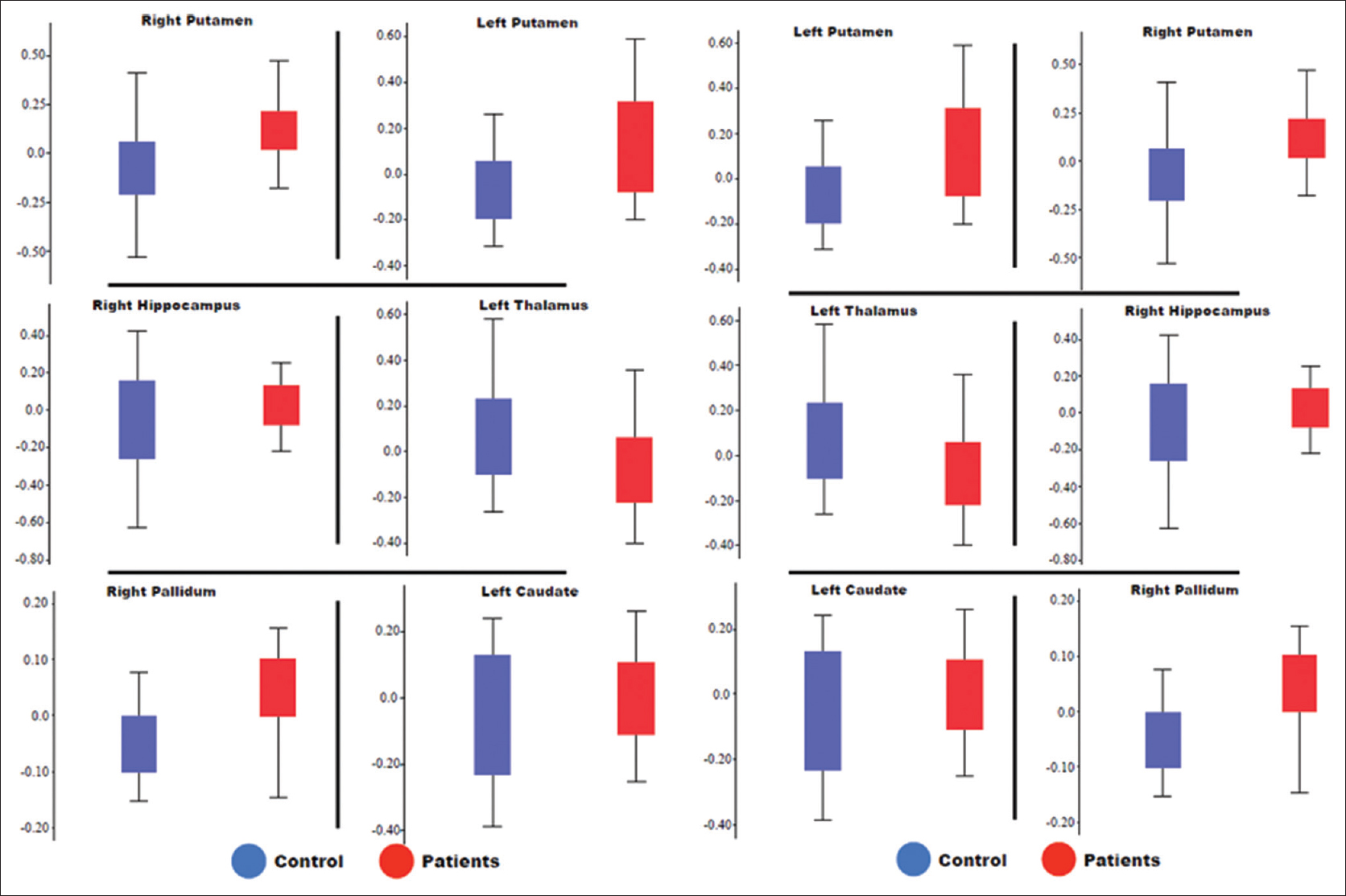

Volumetric analyses

Vertex analysis was performed to evaluate the shape and volume of 15 subcortical structures in SCZ patients and healthy control groups. Six subcortical regions showed significant localized shape differences, right hippocampus (P < 0.005), left and right putamen (P < 0.044 and P < 0.031), left thalamus (P < 0.033), left caudate (P < 0.029), and right pallidum (P < 0.019) [Figure 1]. These results revealed an outward movement of vertices in SCZ patients compared to healthy control participants on the medial-inferior part of the right hippocampus (subiculum), the superior-anterior portion of putamen (both hemispheres), the superior-lateral portion of the left caudate, and the medial-anterior portion of the right pallidum suggesting a volume increase in these regions in SCZ. In contrast, the lateral-medial part of left thalamus showed an inward movement of vertices which express a volume decrease. Figure 2 shows the box-and-whisker plots for both groups' FD values. Significant differences were shown in all six subcortical regions (P < 0.05).

- Statistic maps of shape difference in different subcortical regions (the right hippocampus, left and right putamen, left thalamus, left caudate, and right pallidum) between schizophrenia and control. The red color on the three-dimensional mesh and the yellow circle on the sagittal, coronal, and transverse anatomical slices in standard Montreal Neurological Institute space demonstrate the region with shape significant difference between two groups.

- Box-and-whisker plots showing fractal dimensions of different subcortical regions (the right hippocampus, left and right putamen, left thalamus, left caudate, and right pallidum) for both groups. Red boxes, schizophrenia patients; blue boxes, controls. Boxes enclose 50% of the data and the whiskers show the range.

DISCUSSION

Shape analysis complements volumetric analysis and can identify subtle regional abnormalities on brain structures helping to localize specific pathophysiologic pathways. Our study showed differences in the volumes and shapes of multiple subcortical brain structures in SCZ as compared to healthy populations.

The result showed alterations for the right hippocampus is often seen in studies of SCZ patients.[57816] Our results are consistent about the location of hippocampal shrinkage in the head or anterior region,[561116] and the body or tail.[17] A smaller hippocampus has also been an initiate to be a risk pointer for psychiatry disorder and may indicate an improved vulnerability of the right hippocampus to environmental stress.[418]

Our results are consistent with some other studies about left and right putamen, left thalamus, left caudate and right pallidum.[61112] An outward movement of vertices, medial-inferior part of the right hippocampus (subiculum), superior-anterior portion of putamen (both hemispheres), superior-lateral portion of the left caudate, and the medial-anterior portion of the right pallidum suggesting a volume increase in SCZ.[19]

CONCLUSION

Our results demonstrate deform volumes and shapes of multiple subcortical brain regions in SCZ populations as compared to healthy controls.

These findings may be pertinent to the design and optimization of neurorehabilitation strategies for SCZ patients. However, the present study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results.First, we compared the SCZ with healthy subject making it difficult to draw inference about volume and shape effect directly. Therefore, a longitudinal study would have undoubtedly benefited our predictions of clinical outcomes. The subject group was not homogeneous with respect to SCZ type.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2019/9/1/1/251288

REFERENCES

- Neuromorphometric measures as endophenotypes of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. In: Ritsner MS, ed. Neuropsychiatric Biomarkers, Endophenotypes, and Genes: Promises, Advances and Challenges. Netherlands: Springer; 2009. p. :87-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of socioeconomic deprivation on rate and cause of death in severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:261.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basic symptoms and psychotic symptoms: Their relationships in the at risk mental states, first episode and multi-episode schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:785-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amygdala-hippocampal shape and cortical thickness abnormalities in first-episode schizophrenia and mania. Psychol Med. 2013;43:1353-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:547-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic meta-review and quality assessment of the structural brain alterations in schizophrenia. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:1342-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subcortical neuromorphometry in schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar disorders. Neuroimage Clin. 2016;11:276-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vivo hippocampal subfield volumes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:581-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hippocampal subfield volumes in first episode and chronic schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117785.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hippocampal structure and function in individuals with bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:113-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The function of metabotropic glutamate receptors in thalamus and cortex. Neuroscientist. 2014;20:136-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microstructural organizational patterns in the human corticostriatal system. J Neurophysiol. 2012;107:2984-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thalamic morphology in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:378-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accurate, robust, and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17:479-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- A Bayesian model of shape and appearance for subcortical brain segmentation. Neuroimage. 2011;56:907-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hippocampal shape abnormalities of patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia and their unaffected siblings. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52:527-36.e2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subcortical morphometry and psychomotor function in euthymic bipolar disorder with a history of psychosis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;9:333-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroprotective effect of lithium on hippocampal volumes in bipolar disorder independent of long-term treatment response. Psychol Med. 2014;44:507-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thalamic shape abnormalities in individuals with schizophrenia and their nonpsychotic siblings. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13835-42.

- [Google Scholar]