Translate this page into:

Transient Rotation of a Non-ptotic Kidney Secondary to Acute Pulmonary Thromboembolism

Address for correspondence: Dr. Iman Khodarahmi, Department of Radiology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 150 Bergen Street, UH Suite C-318 A, Newark, New Jersey - 07101-1709, USA. E-mail: iman.khodarahmi@rutgers.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

We present a case of an acquired, transient, rotated right kidney in a 43-year-old woman with an enterocutaneous fistula who presented with acute pulmonary embolism. This non-ptotic rotated kidney returned to its normal orientation within 10 days. We postulate that this transient kidney rotation is due to transient hepatomegaly and passive renal congestion secondary to pulmonary embolism. While in this patient there were no untoward sequelae, it has been reported that ureteral obstruction or vascular occlusion can occur in patients with ptotic and malrotated kidneys, and radiologists, therefore, should be aware of this unusual occurrence and the potential complications.

Keywords

Acquired

hepatomegaly

renal

rotation

thromboembolism

INTRODUCTION

Acquired renal displacements, due to enlargement of adjacent viscera, are less frequent than congenital renal ectopia/malrotation, but have been described.[1234] Renal displacement has also been described to occur in nephroptosis.[5] Occasionally, these displacements are associated with kidney rotation, more commonly on the right side due to space constraints.[34] Here, we report a case of transient right kidney rotation in a patient with a non-ptotic kidney, due to self-limited hepatic congestion and renal enlargement secondary to acute pulmonary thromboembolism. To the best of our knowledge, rapid development and reversibility of acquired kidney rotation secondary to acute pulmonary thromboembolism has not been discussed in the literature.

CASE REPORT

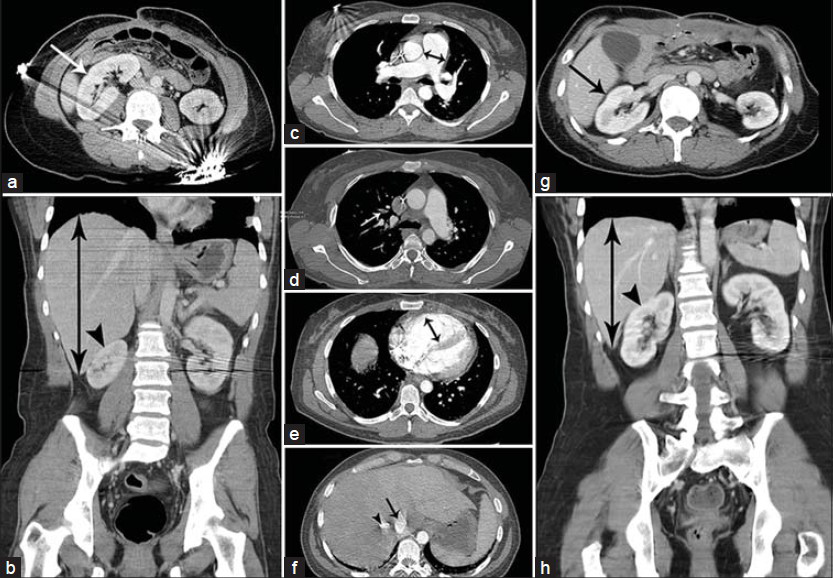

A 43-year-old woman with a prior history of an enterocutaneous fistula, who had required multiple abdominal surgeries, including bowel resections and prior pulmonary embolism, presented to the emergency department with recurrent enterocutaneous fistula and synchronous acute pulmonary embolism. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis on admission demonstrated rotation and mild inferior displacement of the right kidney, with the long axis of the kidney lying in the horizontal plane [Figure 1a and b]. This was a new finding compared with multiple prior CT scans available within the last 2 years in which the kidneys were normally oriented parallel to the psoas muscles. Increased size of both the liver and right kidney was also identified. CT pulmonary angiography performed synchronously for syncope and pulmonary decompensation demonstrated a segmental pulmonary embolism and right heart strain,[6] including reflux of contrast material into the inferior vena cava, interventricular septal bowing, enlarged main pulmonary artery (34 mm), and right ventricular dilatation (RV/LV ratio of 1.8) [Figure 1c–f]. The most recent CT scan done 45 days prior to this admission is shown in Figure 1g and h.

- 43-year-old woman presented with recurrent enterocutaneous fistula and synchronous acute pulmonary embolism, and was subsequently noted to have acquired, transient, rotated right kidney. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the abdomen at presentation (Day 0) shows rotation of the enlarged right kidney (arrow) around its short axis into the horizontal plane. (b) Coronal CECT scan of the abdomen at Day 0 shows hepatomegaly (double head arrow) with rotation of the enlarged right kidney (arrow head) around its short axis into the horizontal plane. (c) Axial CECT scan of the chest at Day 0 shows enlarged main pulmonary artery (double head arrow) measuring 34 mm. (d) Axial CECT scan of the chest at Day 0 shows segmental embolus (arrow) in the anterior branch of the right upper lobe pulmonary artery. (e) Axial CECT scan of the chest at Day 0 shows dilated right ventricle (double head arrow) with RV/LV ratio of 1.8. (f) Axial CECT scan of the liver at day 0 shows reflux of the contrast material into the inferior vena cava (arrow) and hepatic veins (arrow head). (g) Axial CECT scan of the abdomen 45 days before presentation (day –45) shows normal orientation of the normal-sized right kidney (arrow). (h) Coronal CECT scan of the abdomen at Day -45 shows normal orientation of the normal-sized right kidney (arrow head) and normal liver (double head arrow) size.

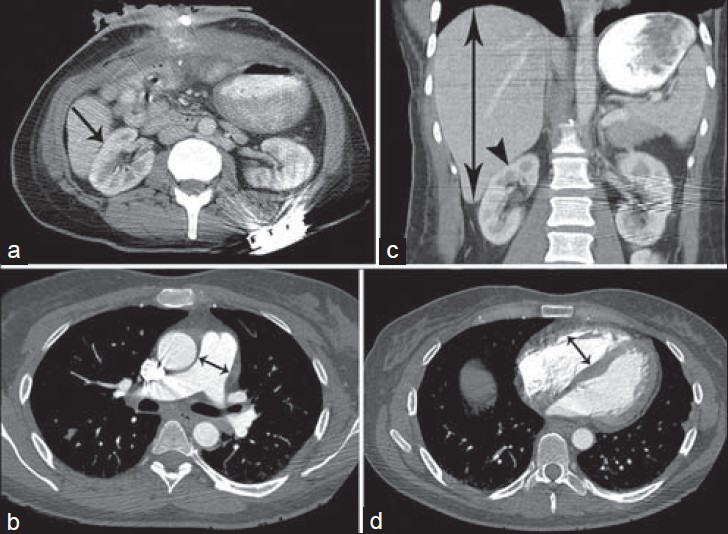

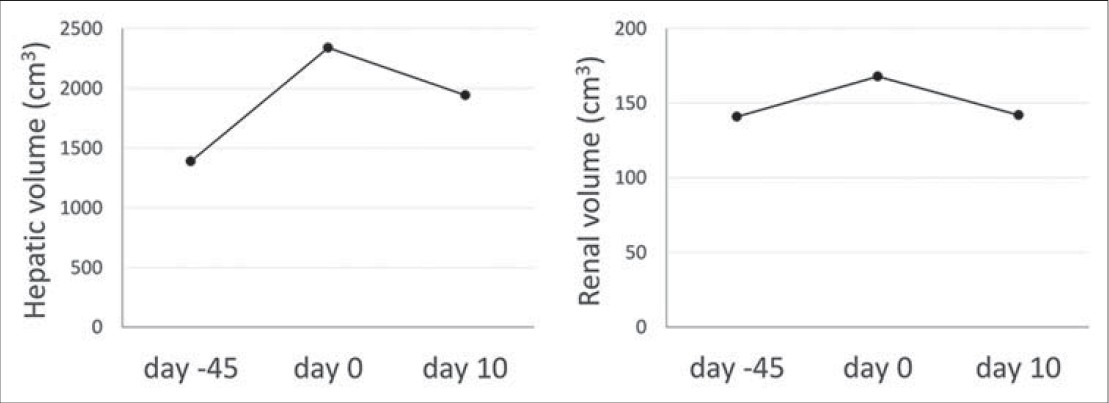

Follow-up imaging done after 10 days demonstrated normalization of the right kidney axis, position, and size, as well as decrease in hepatomegaly [Figure 2a and b]. Calculation of liver and kidney volumes from CT scans done 45 days before presentation, on the day of admission, and 10 days following admission, using the method described by Dello et al.,[7] is presented in Figure 3. Repeat CT pulmonary angiogram [Figure 2c and d] performed 10 days after presentation showed normalization of the thoracic changes including normal size of main pulmonary artery (25 mm) and normal right ventricular size (RV/LV ratio of 0.86). Nephroptosis,[5] which is a condition in which the kidney descends more than two vertebral bodies (or >5 cm) during a position change from supine to upright, was excluded by ultrasound examination of the right kidney which failed to deviate significantly when the patient changed from supine to upright position.

- 43-year-old woman presented with recurrent enterocutaneous fistula and synchronous acute pulmonary embolism, and was subsequently noted to have acquired, transient, rotated right kidney. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the abdomen 10 days after presentation (Day 10) shows return of the right kidney (arrow) to its normal axis. (b) Axial CECT scan of the chest at Day 10 shows normal-sized main pulmonary artery (double head arrow) measuring 25 mm. (c) Coronal CECT scan of the abdomen at Day 10 shows improvement in hepatomegaly (double head arrow) with return of the right kidney (arrow head) to its normal axis. (d) CECT scan of the chest at Day 10 shows normal-sized right ventricle (double head arrow) with RV/LV ratio of 0.86.

- 43-year-old woman presented with recurrent enterocutaneous fistula and synchronous acute pulmonary embolism, and was subsequently noted to have acquired, transient, rotated right kidney. Liver and kidney volumes were calculated 45 days before presentation (Day –45), at presentation (Day 0), and 10 days after presentation (Day 10). The volume of the liver was approximately 1390, 2340, and 1944 cm3 on Days –45, 0, and 10, respectively. The corresponding values for the right kidney were 141, 168, and 142 cm3, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Acquired displacement of the kidney is usually an incidental finding, which may be due to enlarged adjacent organs such as liver, gallbladder, spleen, or adrenal gland. It also occurs in the setting of peritoneal or retroperitoneal masses such as abscesses, hematomas, or neoplasms.[234] This finding is more commonly associated with kidney rotation on the right side than on the left, due to greater space limitations. When caused by hepatomegaly, acquired kidney rotation is usually due to a longstanding process in which the liver enlargement is massive. To the best of our knowledge, rapid development and reversibility of acquired kidney rotation in the absence of nephroptosis has not been discussed in the literature.

Here, we report a case of transient kidney rotation which occurred over a short period of time secondary to passive hepatic congestion related to an episode of acute pulmonary embolism and resolved promptly within 10 days after the resolution of the right heart strain. Hepatic CT volumetry demonstrated a 68% increase in the liver volume at the time of the pulmonary embolism, which may, in part, be due to aggressive hydration after the syncopal episode. However, a few days later, when the right kidney was shown to have returned to its normal anatomical axis and position, the liver volume only decreased by 17%, demonstrating that even small changes in the hepatic size may lead to kidney rotation. A second factor which has been the focus of less attention in the literature is the effect of renal enlargement itself. In the present case, the volume of the kidney increased by 18% at the time of pulmonary thromboembolism and returned to its normal value within 10 days. Therefore, it appears that passive congestion and enlargement of the kidney per se can contribute to renal displacement and/or rotation.

It has been reported that patients with ptotic, ectopic, or malrotated kidneys may develop vascular or ureteral kinking which can cause a spectrum of renal pathologies including hydronephrosis, pyelitis, renal ischemia, and hypertension.[8] While this did not occur in this patient, the potential exists and it is important for radiologists to be aware of this unusual and interesting entity.

CONCLUSION

We report a case of an acquired, transient, rotated kidney in a patient with acute pulmonary embolism secondary to transient hepatomegaly and passive renal congestion that resulted from right heart strain. To the best of our knowledge, rapid development and reversibility of acquired kidney rotation secondary to acute pulmonary thromboembolism has not been discussed in the literature.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2014/4/1/69/148263

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Spectrum of congenital renal anomalies presenting in adulthood. Clin Imaging. 2008;32:183-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Movable Kidney and Other Displacements and Malformations. Charleston: BiblioBazaar; 2010. p. :186-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rotation and forward displacement of the right kidney in hepatomegaly. Anat Clin. 1985;7:137-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes of renal blood flow in nephroptosis: Assessment by color Doppler imaging, isotope renography and correlation with clinical outcome after laparoscopic nephropexy. Eur Urol. 2004;45:790-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT signs of right ventricular dysfunction: Prognostic role in acute pulmonary embolism. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:841-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liver volumetry plug and play: Do it yourself with ImageJ. World J Surg. 2007;31:2215-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Floating kidneys: A century of nephroptosis and nephropexy. J Urol. 1997;158:699-702.

- [Google Scholar]