Translate this page into:

The Rare Sprengel Deformity: Our Experience with Three Cases

Address for correspondence: Dr. Eleni P Kariki, “Papageorgiou” Hospital, Thessaloniki - 56403, Greece. E-mail: eleni.kariki@bath.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Sprengel shoulder is a rare congenital deformity of one or both scapulae that is usually detected at birth. It occurs due to failure of the scapula to descend during intrauterine development and its cause is still unknown. Although the deformity appears randomly most of the time, familial cases have been reported. Sprengel shoulder is often associated with Klippel–Feil syndrome and other congenital skeletal deformities. Anteroposterior X-ray imaging can accurately diagnose Sprengel deformity. However, computed tomography and magnetic resonance scans with three-dimensional reconstruction are nowadays used in everyday practice in order to diagnose concomitant abnormalities, study in detail the anatomy of the affected shoulder(s), and plan appropriate management. We present here our imaging experience from three pediatric cases with Sprengel shoulder and take the opportunity to discuss this rare entity, which is, nevertheless, the commonest congenital defect of the scapula.

Keywords

Birth defects

high scapula

shoulder

Sprengel deformity

undescended scapula

INTRODUCTION

Sprengel deformity, also known as congenital high scapula, undescended scapula, or scapula elevata, is a rare congenital deformity of one or both scapulae that appears at birth,[1] although Pellegrin et al., have published a single case in which the patient presented with Sprengel shoulder reported as appearing after trauma.[2] Undescended scapula results from failed migration of the scapula during early embryonic life,[3] leading to a scapula that protrudes in the neck of the patient. However, the deformity is not simply an aesthetic concern, but more importantly it causes restricted mobility of the shoulder and the cervical spine.[4] Sprengel deformity appears either as a single defect or in association with other abnormalities, most commonly Klippel–Feil syndrome, scoliosis and rib defects.[5] Conventional anteroposterior radiography of the chest including both shoulders is a simple and effective means of diagnosing Sprengel deformity, particularly when combined with appropriate clinical information. Computed tomography (CT) with three-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are necessary nowadays for the diagnosis of coexisting abnormalities and treatment planning. Although the management of Sprengel deformity depends on the severity of the abnormality and the degree of motion restriction, the most common therapeutic choice for patients and orthopedic surgeons is surgical intervention for cosmetic and functional recovery of the shoulder.[5]

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

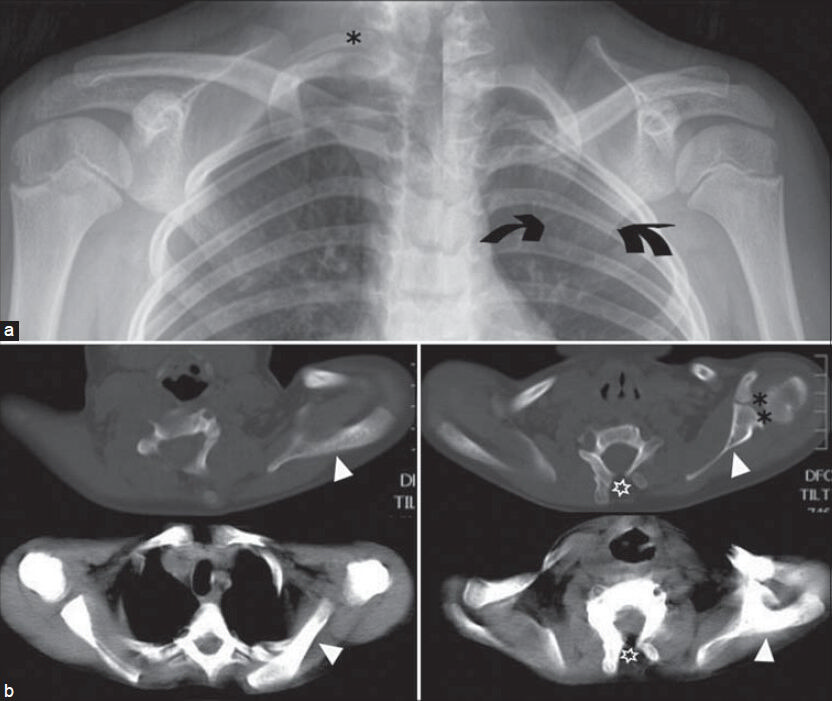

A 6-year-old boy presented with a short neck and bilateral lumps on both sides of his neck. Both scapulae were elevated, although the left one was at a higher level compared to the right one. On physical examination, the patient had limited range of movement of the cervical spine, 60° abduction on his right shoulder, and 90° adduction on his left shoulder, without neurovascular compromise. The little boy was first examined with an anteroposterior X-ray of the thorax and anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the cervical spine [Figure 1], which demonstrated asymmetrically high-positioned scapulae, in conjunction with cervical vertebrae synostosis and thoracic cage deformities. Surgery was decided and a CT scan was performed to delineate the anatomy in detail, assess the degree of asymmetry, and provide the details for morphometric analysis and surgery planning [Figure 2]. The Sprengel deformity was initially corrected on the left side (higher grade) and 5 months later on the contralateral side.

- Case 1. 6-year-old boy who presented with a short neck and bilateral lumps on his neck was diagnosed with bilateral Sprengel deformity. a) An AP X-ray of the thorax shows asymmetrical position of the scapulae and high position of scapular bases (arrows); compare the level of the glenoid cavity (asterisk) and infraglenoid tubercle (arrowhead) on each side. b) An AP X-ray of the cervical–upper thoracic spine demonstrates thoracic spine scoliosis (arrows) and fused ribs (asterisks). c) Lateral X-ray of the cervical–upper thoracic spine shows disturbance of the normal thoracic spine kyphosis (arrows).

- Case 1. 6-year-old boy who presented with a short neck and bilateral lumps on his neck was diagnosed with bilateral Sprengel deformity. Axial CT images a) At the C7 level shows where the right scapula appears (double arrow), the upper third of the left scapula is already visible (arrow). b) At the T1 level where the right acromion lies (closed arrowhead), the scan reveals the left scapular body just inferior to the scapular spine (open arrowhead). c) At the T2, the scan shows the level of the upper part of the body of the right scapula (asterisk), only the lower third of the left scapular body (double asterisk), as is expected since the right scapula is at a lower level compared with the left one.

Case 2

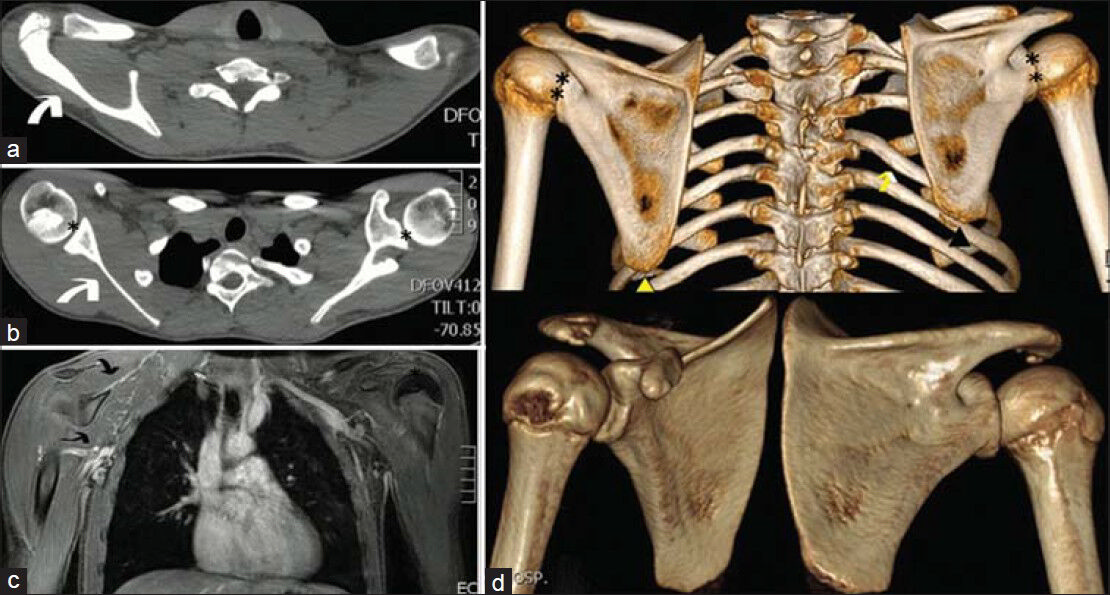

A 7-year-old girl was referred to our department for imaging studies prior to surgical repair of her left undescended scapula. She had been diagnosed with Klippel–Feil syndrome and Sprengel deformity of the left scapula when she was 6-months old. Since then, she had been undergoing physiotherapy and it was now decided to treat her surgically. Anteroposterior X-ray scans of the shoulders were performed, followed by a CT and an MRI scan, in order to evaluate the omovertebral association and demonstrate the spectrum of abnormalities that was required for thorough planning of surgery [Figures 3 and 4].

- Case 2. 7-year-old girl with Klippel–Feil syndrome and left Sprengel deformity referred for imaging studies before operative intervention. a) A synthesis AP X-ray of the right and left shoulder shows the undescended and medially rotated left scapula (arrows). There is also a right cervical rib (asterisk). b) Axial CT images at the level of lower cervical vertebrae show the left scapula (white arrowheads) and the left glenohumeral joint (double asterisk) lying at a higher level compared to the contralateral side. There are also cervical unfused vertebral arches (empty asterisks).

- Case 2. 7-year-old girl with Klippel–Feil syndrome and left Sprengel deformity. 3D-CT reconstruction images show the difference between the position of the scalpulae: (a and b) giving the superior displacement of the affected scapula relative to the normal one. The A/B ratio measures the rotational deformity of the affected scapula. Lines A and B are drawn between the inferior scapular angle (yellow arrowhead) and a line perpendicular to the axis along the spinous processes (asterisks). Lines A and B connect the center of the glenoid cavity (green dots) to the medial border of the scapular spine (blue dots).

Case 3

A 14-year-old boy visited our department for investigation of an undetermined deformity on the right side of his neck. CT and MRI scans were performed. These revealed a mild Sprengel deformity and provided the details of the bony associations and anatomy of extra-osseous structures as needed for preparation of the intervention [Figure 5].

- Case 3. 14-year-old boy with a right-sided nuchal deformity, shown with CT and MRI to be a Sprengel scapula. (a and b) Axial CT-scan images demonstrate the elevated position of the right scapula (white arrows). The shoulder joints (asterisks) are asymmetrical. (c) Coronal MRI reveals mildly hypoplastic musculature of the right shoulder (double arrow). (d) 3D-CT reconstruction images show that the right scapula (black arrowhead) is higher than the left (yellow arrowhead). Note the associated deformity of the rib cage on the right side (yellow arrow) and the asymmetry of the shoulder joints (double asterisks).

DISCUSSION

Otto Sprengel published four clinical cases of upward dislocation of the scapula in 1891.[6] However, Michael Eulenberg, a German surgeon, was the first to describe the anatomy of one case of an undescended scapula in 1863, and claimed that it occurred due to traumatic dislocation of the scapula.[7] Alfred Willet and William Walsham described another case in 1883, in which the high scapula was associated with the formation of an osteochondral bridge with the lower cervical vertebrae.[7] After Sprengel, Vittorio Putti, an Italian radiologist and orthopedic surgeon, further studied and described the anatomical abnormalities of a Sprengel shoulder.

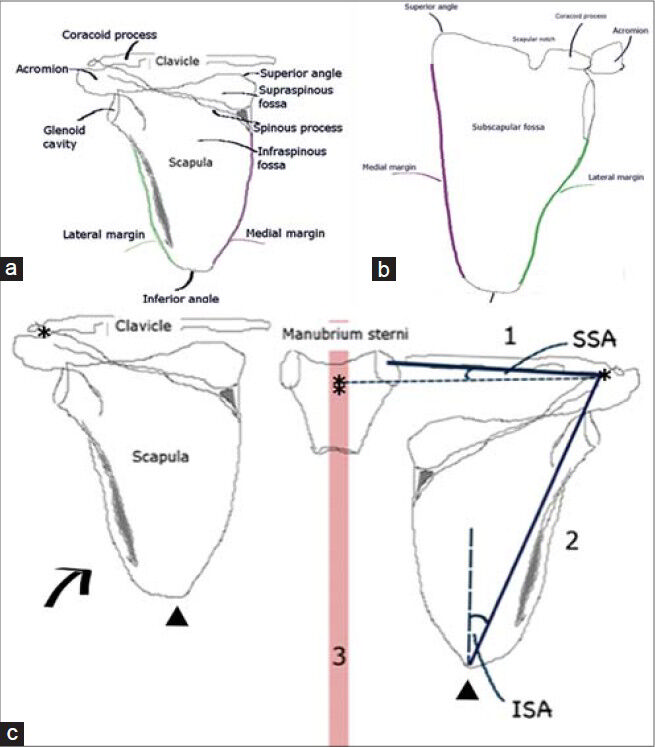

The embryonic primordium of the scapula appears during the fifth week of intrauterine life and acquires the final morphology by the end of the eighth week (end of embryonic period).[3] It initially appears at the level of the fourth to fifth cervical vertebrae.[3] During the same period, the brachial plexus gives rise to the peripheral nerves of the upper limb, which operates as a stimulus for development of the upper limb muscles.[3] During its growth, the scapula descends over the upper five ribs to reach the correct anatomical position that holds at birth.[3] This developmental migration of the scapula reflects a progressive adaptation of the bone, which serves for brachiation and not for bearing weight.[3] The increased demands for greater range of movement and flexibility in humans have altered the morphology and dynamics, both of the shoulder joint and the scapula. The scapula acquired a spine, enlarged in size, especially in the part beneath its spine, widened (high breadth to length ratio), and moved backward, standing at an angle of approximately 45° relative to the midline[3] [Figure 6]. Failure of scapula to descend leads to Sprengel deformity, in which case the bone sits 2–10 cm higher than expected. The maintenance of high position of the scapula in the process of skeletal development leads to a series of other musculoskeletal defects including hypoplasia, medialization, and adduction[8] of the scapula, prominence of its upper angle, distal rotation and lateral angulation of the glenoid cavity, changes in the position of the clavicle, anomalies of the cervicothoracic vertebrae and ribs, and muscular hypoplasia or atrophy of the shoulder musculature.[5] A fibrous structure may bridge the cervical spine with the undescended scapula, which when ossified is called the omovertebral bone (omo derives from the Greek word for shoulder “ώμoς”). The result in practice is limitation of the abduction at the shoulder joint[3578] and “growing out” of the shoulder blade.[7]

Although Sprengel deformity is rare, it is described as the commonest congenital defect of the scapula and nowadays, as a rule, it is recognized either at birth or in early childhood. Its cause is unknown and there have been only very few cases of familial Sprengel deformity described. Most authors agree that the undescended scapula affects women three times more often than men, although Kadavkolan and others report that the entity occurs equally in both sexes.[9] It can occur on both sides concurrently but is most often unilateral, with a predilection for the left side. Although patients with bilateral Sprengel deformity might seem less disfigured, their functional limitation is more debilitating, compared to patients with a unilateral defect. Since the affected scapula is not only mis-positioned but also smaller than the bone on the other side, it is often difficult to accurately estimate the grade of the defect, especially in bilateral Sprengel shoulder. In other words, the estimation of the height difference between the healthy-sat and the high-sat scapula using the easily visualized inferior angle of the scapulae on an anteroposterior X-ray of the chest is not always accurate enough for the estimation of the severity of the deformity and for choosing the appropriate treatment.

- Line drawings show normal anatomy, (a) dorsal and (b) ventral views of the left scapula, and (c) Sprengel deformity. The affected scapula (arrow) sits 2-10 cm higher than normal in medial rotation: 1, the line from the midpoint of the acromioclavicular joint (asterisks) to the midpoint of the sternoclavicular joint (double asterisk); 2, the line connecting the middle of the acromioclavicular joint (asterisks) to the inferior angle of the scapula (arrowheads); and 3, a line along the spinous processes of the vertebrae (red line). SSA: Superior scapular angle, ISA: Inferior scapular angle.

There have been various indices proposed for the study of the morphology of the scapula and the estimation of the degree of scapular deformity. The scapular index is an indicator of the relationship between the breadth and the length of the scapula. It measures the width along the base of the scapula (length of spinous process), the length between its superior and inferior angles, and it is expressed as a percentage (100 × scapular breadth/scapular length). The infraspinatus index describes the width of the scapula relative to the length of the infaspinatus fossa. Both of these indices are estimated radiologically. Table 1 shows the clinical and radiologic classification of Sprengel deformity.[58910]

CONCLUSION

CT with 3-D reconstruction and MRI are particularly useful for the accurate calculation of the degree of Sprengel deformity, determination of associated osseous and/or muscular deformities, and for choosing and planning the treatment. Considering that surgical treatment, when appropriate, is better applied when the child is under 8 years of age, early and accurate diagnosis of the deformity is important. CT 3-D images are a powerful tool for detailed study of the anatomical features of the bony structures in Sprengel deformity. This evaluation is necessary to understand the morphological characteristics, biomechanics, and etiology of this entity.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2014/4/1/55/143407

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Bilateral congenital undescended scapula (sprengel deformity) Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:374.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sprengel deformity presenting as a post-traumatic injury in an afgan boy: A case report. Mil Med. 2013;178:e1379-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Developmental anatomy of the shoulder and anatomy of the glenohumeral joint. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, eds. The Shoulder (4th ed). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009. p. :1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sprengel deformity: Pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surt. 2012;20:177-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term results of modified green method in sprengel's deformity. J Child Orthop. 2010;4:309-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Die angeborene verschiebung des schulterblattes nach oben. Archiv Fur Klinische Chirurgie. 1891;42:545-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A second case of malformation of the left shoulder-girdle; removal of the abnormal portion of bone; with remarks on the probable nature of the deformity. Med Chir Trans. 1883;66:145-1583.

- [Google Scholar]

- Woodward procedure improves shoulder function in Sprengel deformity. Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:403-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sprengelen deformity of the shoulder: Current perspectives in management. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2011;5:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sprengel deformity: Morphometric assessment and surgical treatment by the modified green procedure. J Pediatr Orthop. 2014;34:55-62.

- [Google Scholar]