Translate this page into:

Survival and clinical success of endovascular intervention in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome: A systematic review

*Corresponding author: Xinwei Han, Department of Interventional Radiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China. hanxinwei2006@163.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mukhiya G, Jiao D, Han X, Zhou X, Pokhrel G. Survival and clinical success of endovascular intervention in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome: A systematic review. J Clin Imaging Sci 2023;13:5.

Abstract

Budd-Chiari syndrome is a complex clinical disorder of hepatic venous outflow obstruction, originating from the accessory hepatic vein (HV), large HV, and suprahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC). This disorder includes both HV and IVC obstructions and hepatopathy. This study aimed to conduct a systematic review of the survival rate and clinical success of different types of endovascular treatments for Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS). All participant studies were retrieved from four databases and selected according to the eligibility criteria for systematic review of patients with BCS. The survival rate, clinical success of endovascular treatments in BCS, and survival rates at 1 and 5 years of publication year were calculated accordingly. A total of 3398 patients underwent an endovascular operation; among them, 93.6% showed clinical improvement after initial endovascular treatment. The median clinical success rates for recanalization, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), and combined procedures were 51%, 17.50%, and 52.50%, respectively. The median survival rates at 1 and 5 years were 51% and 51% for recanalization, 17.50% and 16% for TIPS, and 52.50% and 49.50% for combined treatment, respectively. Based on the year of publication, the median survival rates at 1 and 5 years were 23.50% and 22.50% before 2000, 41% and 41% in 2000‒2005, 35% and 35% in 2006‒2010, 51% and 48.50% in 2010‒2015, and 56% and 55.50% after 2015, respectively. Our findings indicate that the median survival rate at 1 and 5 years of recanalization treatment is higher than that of TIPS treatment, and recanalization provides better clinical improvement. The publication year findings strongly suggest progressive improvements in interventional endovascular therapy for BCS. Thus, interventional therapy restoring the physiologic hepatic venous outflow of the liver can be considered as the treatment of choice for patients with BCS which is a physiological modification procedure.

Keywords

Budd-Chiari syndrome

Endovascular interventional treatment

Survival rate

systematic review recanalization

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemaic shunt

INTRODUCTION

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) is a complex clinical disorder of hepatic venous outflow obstruction, originating from the accessory hepatic vein (HV), large HV, and suprahepatic inferior vena cava (IVC).[1] This disorder includes both HV and IVC obstructions and hepatopathy.[2] Partial or complete obstruction of the IVC with membranous or segmental lesions was considered to be the main cause of BCS in Asian countries.[3] The membranous obstruction of the IVC contributes to two-thirds of patients with BCS in Asia.[4] Most patients with BCS present late after developing symptoms or in their chronic conditions, whereas only a small number of patients present with an acute and fulminant type of BCS.[5] BCS is more commonly seen in adults than in children; when seen in children, clinical manifestations are similar to those in adults.[6] Endovascular intervention treatment has emerged as an advanced therapeutic option for patients with BCS. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedures have rapidly replaced the traditional surgical shunt on account on their due to minimal invasiveness, low blood loss, low infection rate, quick recovery, shorter hospital stay, and increased long-term survival rate.[7,8] TIPS significantly reduced portal venous pressure through placement of an artificial stent from the portal vein to the HV. The patency of shunts has greatly improved since the adoption of dedicated polytetrafluoroethylene stents.[9] Recanalization is a physiological procedure that maintains natural blood flow in the HV/IVC.[10] It can minimize the risk of hepatic encephalopathy, and remains a first-line treatment option for patients with BCS.[11,12] One-third of short-length HV stenosis was treated with recanalization by percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) with or without stent placement.[13,14] Recanalization has shown promising results in Asian countries with excellent clinical outcomes and higher survival rates.[15] The European Association for the Study of the Liver recommended a stepwise therapeutic algorithm for BCS. The algorithm depends on treatment response, medical therapy with anticoagulant drugs, angioplasty, stent placement, TIPS, and liver transplantation.[16] The prognosis of patients with BCS depends on the onset of obstruction in vessels with anatomical location and liver dysfunction. However, new developments and improvements in radiological endovascular therapy and early diagnosis have increased the survival rate of patients with BCS.

The present systematic review aimed to evaluate the survival rate of BCS after different types of endovascular intervention, clinical success after initial different types of endovascular intervention treatment, and survival rate of BCS in the publication year.

METHODS

Search strategy

Relevant studies were searched in PubMed, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE databases, and the necessary data were retrieved. The last search was performed on February 17, 2021. Our search items included the following: Budd-Chiari syndrome, HV obstruction, or hepatic venous thrombosis, endovascular treatment in BCS or interventional treatment in BCS, PTA for BCS, TIPS for BCS, or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting for BCS.

Data selection

All published articles met the eligibility criteria according to the population, interventions, comparison, outcomes, and study results. The study selection process was demonstrated in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis guidelines [Figure 1].

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis flow diagram of studies selection process.

The inclusion criteria were: (1) Retrospective studies, prospective studies, including case-control studies were eligible; (2) all the previous studies reporting the survival rate and clinical success; (3) full article papers with detailed information and statistical results of intervention treatment; and (4) there were no publication data, publication language, or publication status restrictions.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Duplicate studies; (2) studies that were not original papers; (3) studies unrelated to the subject matter of this review; (4) case reports; (5) comments; (7) essays; (8) abstracts; (9) not reporting relevant clinical outcomes; (10) lack of details results; (11) review articles; (12) fewer than ten patients; (13) studies unmatched inclusion criteria; and (14) studies with missing survival rate, re-intervention rate, and clinical success.

Data extraction

In a data extraction sheet, information regarding the first author, publication year, country, number of patient participants in individual studies, sex, mean age, type of endovascular treatment, clinical success rate, total follow-up, and survival rate at 1 and 5 years after initial endovascular treatment was extracted for further analysis.

Quality assessment

Studies were considered to be of higher quality if they fulfilled all the following predetermined criteria: (1) Patients were admitted to the hospital consecutively; (2) the interval of enrollment and eligibility criteria was recorded; (3) the length of follow-up and number of deaths were reported; (4) patients were diagnosed with BCS and treated with endovascular intervention procedures; and (5) survival analysis and clinical success were reported.

Definition

HV Angioplasty/Stenting: When the stiff guide wire was established, a balloon dilator catheter of 12–15 mm diameter was inserted from the right jugular vein puncture site to the obstructed part of HV through the guide ware. Next, the balloon catheter was dilated twice, and each dilatation occurred 40s. If there was more than 30% residual stenosis on HV venography after balloon dilated then a stent was inserted in the stenosis part of the HV.

IVC Angioplasty/Stenting: Venography was performed to evaluate the IVC anatomy and obstruction characteristics. Next, a guide wire with a balloon catheter (25-30mm) was used to dilatation IVC stenosis parts. A self-expandable metallic stent was used if the IVC narrowed immediately after dilated or more than 30% residual stenosis on IVC venography after balloon dilation.

Recanalization

It was performed with balloon dilation or endovascular stent placement in the stenosis part of HV and IVC.

TIPS/direct intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (DIPS)

It was performed in symptomatic patients with nonrecanalization HV obstruction, portal hypertension, refractory ascites, variceal bleeding, and long segment obstruction HV. DIPS usually used in failed TIPS, occluded three major HVs and anomalies of HVs.

Technical success

Technical success of recanalization was defined as the complete elimination of HV or IVC obstruction and confirmed by venography. Technical success of TIPS was defined as the successful placement of an artificial stent between the HV and the portal vein. The stent position was confirmed by angiography, and the contrast medium flowed back into the right atrium smoothly through the intrahepatic shunt.

Data analysis

We summarized the 1- and 5 years survival rates according to different types of endovascular intervention treatment mortalities and publication years in an Excel worksheet. Then, a box plot was drawn to describe the median survival rate with range using SPSS software (version 16.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

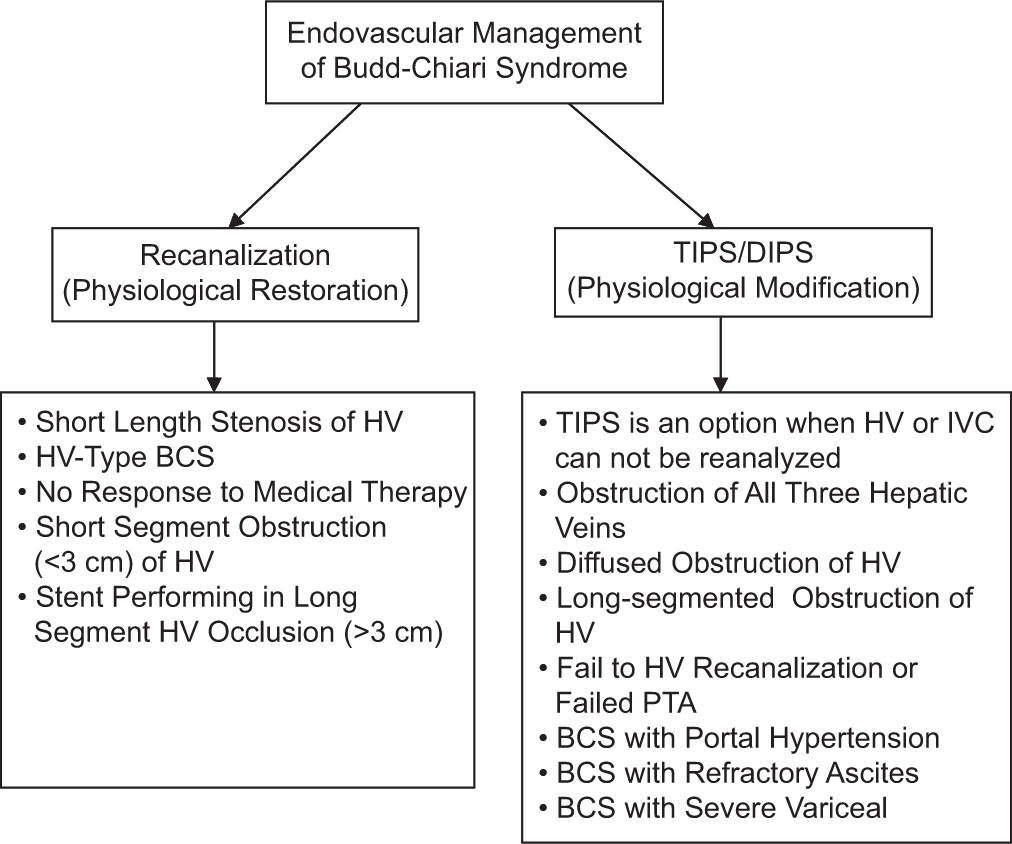

- Flow chart of indication of the endovascular management in BCS

RESULTS

Overview on basic characteristics of the included studies

Overall, 2865 articles were retrieved, of which 56 studies with complete information regarding the survival rate and clinical success of the endovascular intervention in patients with BCS patients were included in the final systematic review.[8,10,11-13,17-68] All selected studies were published between 1995 and 2019. Of these, 40 individual studies were published after 2010. Twenty-seven studies were conducted in China, whereas 29 studies were conducted outside China. The basic characteristics of these studies are summarized in [Tables 1 and 2].

| S. No. | Studies characteristics | Number | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Total previous studies retrieved | 56 | 100 | ||

| 2. | Publication year between (1995 and 2019) | ||||

| 3. | Last search performed – 17-02-2020 | ||||

| 4. | Publication year studies <2000 2000–2005 2006–2010 2011–2015 2016–2019 |

4 7 5 18 22 |

7.1 12.5 8.9 32.1 39.2 |

||

| 5. | Region conducted study Eastern Asia (China, and Japan) Oceania (Australia) South Central Asia (India) Middle East (Egypt, Turkey and Saudi Arabia) Europe (UK, Germany, Italy, France, Netherland, Greece , Sweden, and Denmark) North America (USA) |

28 1 7 3 15 2 |

50 1.7 12.5 5.3 26.7 3.5 |

||

| 6. | Type of endovascular treatment Recanalization (PTA with or without stent) Combined (Recanalization and TIPS) TIPS |

26 16 14 |

46.4 28.5 25 |

||

| 7. | Total patient attempted endovascular procedure | 3398 | 100 | ||

| 8. | Total Technical successful endovascular procedures | 3321 | 97.7 | ||

| 9. | Total clinical successful after initial endovascular treatment >90–100% 70–90% <70 |

3109 45 9 2 |

93.6 80.35 16.07 3.57 |

||

| 10. | Median clinical success Recanalization TIPS Combined procedures |

51 18.50 55.50 |

|||

| 11. | Survival rate At 1 year At 5 years >90–100% - Good survival rate 70–90% - Moderate survival rate <70 - Poor survival rate |

3220 3099 |

96.9 93.3 |

||

| 1 yr 51 5 0 |

5 yrs 40 15 1 |

1 yr 91 8.9 0 |

5 yrs 71.4 26.7 1.7 |

||

| 12. | Median survival rate Recanalization TIPS Combined procedures Survival rate of publication year <2000 2000–2005 2006–2010 2011–2015 >2015 |

1 yrs | 5 yrs | ||

| 51 17.50 52.50 23.50 41 35 51 56 |

51 16 49.50 22.50 41 35 48.50 55.50 |

||||

| 13. | Follow-up 12 months >60 months >96 months >120 months |

56 56 31 19 |

100 100 53.4 32.7 |

||

PTA: Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

| 1st author/Years of published/Reference | Country | N.P | M/F | Mean Age | Stents | Type of Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Company | Recanalizetion | TIPS/DIPS | Stent | Angio | |||||

| Zahn et al., 2010[8] | Germany | 13 | 3/10 | 14–60 | Palmaz Self-expandable Covered Viatorr stent |

Jonhson and Jonhson USA Wallstent Schneider, Bülach, Switzerland GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA |

--- | 13 | --- | --- |

| Rössle et al., 2004[10] | Germany | 35 | 8/27 | 12–74 | Palmaz Self-expandable Memotherm stent Sinus stent Covered Viatorr stent |

Jonhson and Jonhson USA Wallstent Schneider, Bülach, Switzerland Angiomed, Karlsruhe, Germany Optimed, Ettlingen, Germany Gore Medical, Munich, Germany |

--- | 33 | --- | --- |

| Pavri et al., 2014[17] | USA | 21/47 | 16/31 | 31–69 | N/A | N/A | --- | 21 | --- | --- |

| Mahmoud et al., 1995[18] | UK | 44 | 17/27 | 14–60 | N/A | N/A | 11 | --- | 3 | 8 |

| Rosenqvist et al., 2016[19] | Sweden | 13 | 6/7 | 16–63 | Covered Viatorr stent | Gore Medical, USA | --- | 13 | --- | --- |

| Tripathi et al., 2014[20] | UK | 67 | 21/46 | 15–70 | Covered Viatorr sten Uncovered stent Uncovered metal stent |

GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA Wallstent® Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA Memotherm, Angiomed, Karlsuhe, Germany |

--- | 67 | --- | --- |

| Sonavane et al., 2018[21] | India | 42 | 26/16 | 19–68 | N/A | N/A | --- | 42 | --- | --- |

| Hayek et al., 2016[22] | France | 54 | 20/34 | 15–67 | Covered self-expandable Uncovered stent Covered stent graft viatorr |

Wallgraft, Boston Scientific; Fluency, Bard Incorporated, Karlsruhe, Germany Wallstent, Boston Scientific. GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA |

--- | 53 | --- | --- |

| Shalimar et al., 2017[23] | India | 80 | 40/40 | 12–50 | Covered Viatorr sten Uncovered stent Covered stent |

GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA Fluency plus; BARD Inc |

--- | 80 | --- | --- |

| Murad et al., 2007[24] | Netherland | 17 | 10/6 | 19–50 | Covered Viatorr sten Self-expandable Bare stents |

GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA Wallstent, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA |

--- | 16 | --- | --- |

| Molmenti et al., 2005[25] | USA | 11 | 5/6 | 22–78 | Uncovered | Wallstent, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA |

--- | 10 | --- | --- |

| Garcia-Pag et al., 2008[26] | Italy | 133 | 78/46 | 35–40 | Uncovered stent (61) Covered stent (48) Both stent (15) |

N/A | --- | 124 | --- | --- |

| Fitsiori et al., 2013[27] | Greece | 14 | 3/11 | 3–66 | Bare metal stent E-Polytetrafluoroethylene stent graft |

N/A GORE, Flagstaff, AZ, USA |

--- | 14 | --- | --- |

| Neumann et al., 2013[28] | Denmark | 14 | 3/11 | 17–66 | Uncovered stent (10) Covered stent (4) |

N/A | --- | 14 | --- | --- |

| Corso et al., 2008[29] | Italy | 15 | 7/8 | 7–52 | Self-expandable metallic stents (8) Covered stent graft (7) |

Wallstent, Boston Scientific, Watertown, WI, USA, Viatorr Endoprothesis, W.L. Gore Medical, Flagstaff, AZ, USA |

--- | 15 | --- | --- |

| Kathuri et al., 2014[30] | India | 25 | 16/9 | 2–16 | N/A | N/A | 25 | --- | 20 | 5 |

| Khuroo et al., 2005[31] | Soudi arabia | 16/40 | 17/23 | 15–64 | Self-expandable stent | Wallstent, Boston Scientific, Watertown, WI, USA |

6 | 8 | --- | 6 |

| Jagtap et al., 2017[32] | India | 88 | 52/36 | 20–56 | N/A | N/A | 75 | 0/13 | 64 | 73 |

| Amarapurkar et al., 2008[33] | India | 38/49 | 24/25 | 1–57 | Uncovered stent Covered stent |

N/A N/A |

22 | 15 | 22 | 2 |

| Mo et al., 2017[34] | Australia | 27 | 11/14 | 21–76 | N/A | N/A | 11 | 18 | 11 | 11 |

| Zhang et al., 2013[35] | China | 18 | 15/3 | 19–50 | N/A | N/A | 15 | 3 | --- | 15 |

| Meng et al., 2016[36] | China | 55 | 39/14 | NA | Bare stents Fluency covered stent |

N/A BARD Peripheral Vascular, Inc., Tempe, Arizona |

53 | 5 | 47 | 53 |

| Rathod et al., 2016[37] | India | 190 | 102/88 | 15–55 | Covered stent grafts Niti-S TIPS stent Fluency stent graft |

Viatorr, W. L. Gore and associates, Arizona, USA Taewoong Medical Co. Ltd., S.Korea Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc., Arizona, USA |

84 | 106 | 84 | 78 |

| Bi et al., 2018[38] | China | 60 | 48/12 | 12–76 | Bare stent E-Luminexx stent Covered fluency stents |

Bard Peripheral Vascular, Tempe, Arizona Bard Incorporated, Karlsruhe, Germany |

31 | 27 | --- | 31 |

| Al-Warraky et al., 2015[39] | Egypt | 103 | 30/73 | 14–44 | Uncovered Covered |

Wallshunt, Watertown, WI, USA Gore medical, Flagstaff, AZ, USA |

26 | 55/22 | --- | 26 |

| Eapen et al., 2005[40] | UK | 61 | 22/39 | 16–67 | N/A | N/A | 32 | 29 | 8 | 24 |

| Fan et al., 2016[41] | China | 60 | 27/33 | 18–60 | Bare metal stent Stent-Graft |

N/A N/A |

27 | 33 | --- | 27 |

| Seijo et al., 2013[42] | Europe | 70 | NA | 16–83 | N/A | N/A | 8 | 62 | --- | 8 |

| Bi et al., 2018[43] | China | 40 | 32/8 | 28–76 | N/A | N/A | 40 | 3 | 2 | 40 |

| Cui et al., 2015[13] | China | 17 | 8/6 | 25–66 | N/A | N/A | 14 | --- | 2 | 12 |

| Xue et al., 2009[44] | China | 53 | 39/14 | 11–70 | N/A | N/A | 47 | 2 | 34 | 13 |

| Ding et al., 2018[45] | China | 108 | 69/39 | 25–74 | N/A | N/A | 107 | --- | 13 | 94 |

| Xu et al., 1996[46] | China | 32 | 6/26 | 20–56 | N/A | N/A | 31 | --- | 17 | 20 |

| Zhou et al., 2017[47] | China | 47 | 33/14 | 21–71 | N/A | N/A | 61 | --- | --- | 61 |

| Yang et al., 2019[48] | china | 33 | 16/17 | 44–74 | N/A | N/A | 33 | --- | 15 | 18 |

| Huang et al., 2016[49] | China | 265 | 131/134 | 18–79 | N/A | N/A | 263 | --- | 56 | 263 |

| Chen et al., 2017[11] | China | 68 | 39/29 | 22–52 | N/A | N/A | 68 | --- | 8 | 60 |

| Sang et al., 2014[50] | China | 48 | 31/17 | 25–65 | N/A | N/A | 43 | --- | 31 | 43 |

| Srinivas et al., 2012[51] | India | 12 | 7/5 | 28–55 | N/A | N/A | 12 | --- | 5 | 7 |

| Qiao et al., 2005[52] | China | 44 | 25/19 | 19–77 | N/A | N/A | 45 | --- | 45 | --- |

| Bi et al., 2018[53] | China | 72 | 43/29 | 22–76 | N/A | N/A | 91 | --- | --- | 91 |

| Zhang et al., 2003[54] | China | 115 | 65/50 | 17–67 | N/A | N/A | 122 | --- | 122 | --- |

| Tripathi et al., 2016[55] | UK | 63 | 27/36 | 15–55 | N/A | N/A | 63 | --- | 31 | 32 |

| Ding et al., 2015[56] | China | 93 | 59/34 | 15–72 | N/A | N/A | 93 | 2 | 93 | |

| Fu et al., 2011[57] | China | 18/29 | 13/16 | 23–67 | N/A | N/A | 22 | --- | --- | 22 |

| Cheng et al., 2018[12] | China | 69 | 43/26 | 15–72 | N/A | N/A | 66 | --- | 11 | 66 |

| Yu et al., 2019[58] | China | 56 | 30/26 | 29–65 | N/A | N/A | 55 | --- | --- | 55 |

| Wu et al., 2002[59] | China | 42 | 28/14 | 12–62 | N/A | N/A | 41 | --- | ---- | 41 |

| Han et al., 2013[60] | China | 177 | 93/75 | 12–62 | N/A | N/A | 168 | --- | 117 | 168 |

| Fu et al., 2015[61] | China | 62 | 33/27 | 24–72 | N/A | N/A | 60 | --- | 11 | 58 |

| Wang et al., 2013[62] | China | 29 | NA | NA | N/A | N/A | 28 | --- | 18 | --- |

| Fu et al., 2015[63] | China | 66 | 34/32 | 21–79 | N/A | N/A | 66 | --- | 18 | 50 |

| Kucukay et al., 2016[64] | Turkey | 32 | 18/14 | 20–42 | N/A | N/A | 30 | --- | --- | 30 |

| Boyvat et al., 2008[65] | Turkey | 11 | 5/6 | 6–43 | Bare metal stent | Wallstent, Boston Scientific | --- | 11 | --- | --- |

| Griffith et al., 1996[66] | UK | 18 | 8/10 | 16–65 | N/A | N/A | 18 | --- | 6 | 18 |

| Yang et al., 1996[67] | China | 42 | 28/14 | 16–56 | N/A | N/A | 38 | --- | --- | 38 |

| Gao et al., 2011[68] | China | 197 | 89/108 | 16–62 | N/A | N/A | 197 | --- | --- | 197 |

TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, DIPS: Direct intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

A total of 3398 patients underwent endovascular intervention; among them, 93.6% achieved clinical improvement after initial interventional endovascular treatments. Recanalization was used in 26 studies, TIPS in 14 studies, and combined procedures in 16 studies [Table 1]. According to the follow-up duration, 56 studies recorded a follow-up period of more than 60 months, 31 studies of 96 months, and 19 studies for more than 120 months [Table 1].

Study quality

Patients were consecutively admitted to the hospital in 54 (96.42%) studies. From the total 56 studies, 51 (91.07%) studies were considered to be of good quality whereas five (8.92%) were of poor quality. The interval between enrollment and eligibility criteria was recorded for all the included studies. All patients were diagnosed with BCS and treated with endovascular intervention procedures accordingly. Fifty-one studies showed a good survival rate, and only five showed a moderate survival rate at 1 year. Similarly, 40 studies had good survival rates, 15 studies had moderate survival rates, and only a single study had a poor survival rate at 5 years [Table 1].

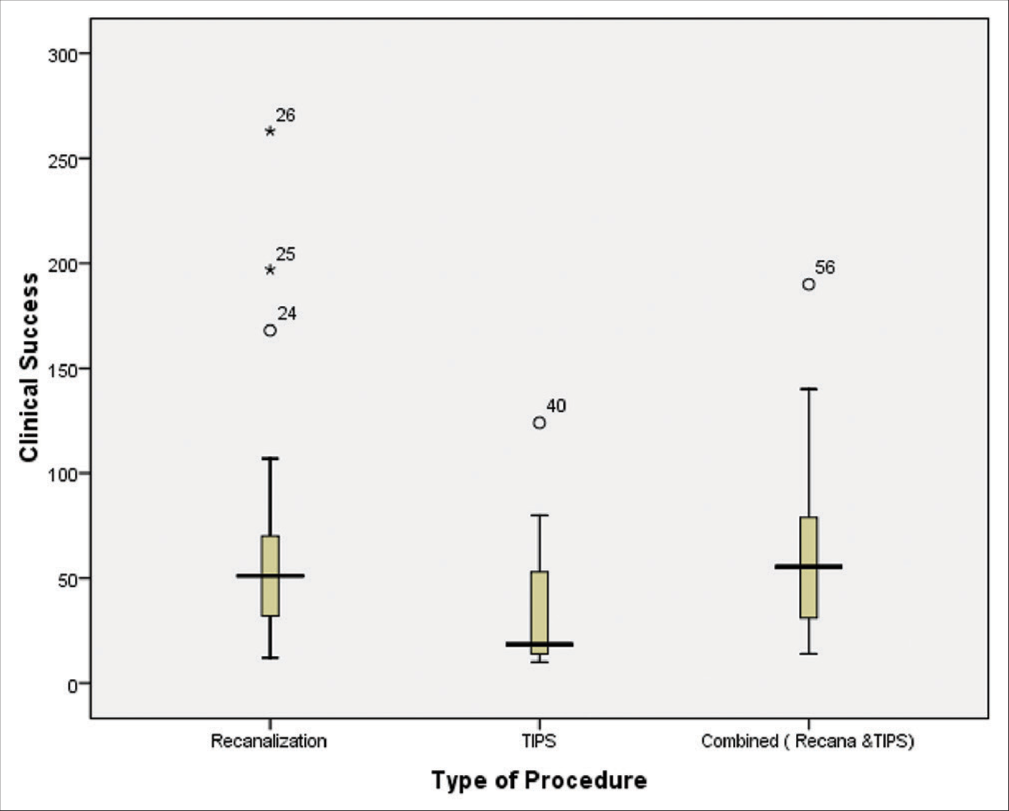

Clinical success in different types of interventional endovascular procedures

The overall clinical success rate of endovascular intervention in patients with BCS was 93.6%. The median clinical success of recanalization procedures was 51% (range: 32–70%) in 26 studies, in which the patients were treated with angioplasty with or without stent; for the combined procedures was 55.50% (range: 31‒79%) in 16 studies, in which patients were treated with recanalization (angioplasty with or without stent) and TIPS. TIPS procedure was 18.50% (range: 14– 53%) in 14 studies, where patients were treated with TIPS [Figure 2].

- Box plot of median clinical success in different types of endovascular procedures (recanalization procedure in 26 studies; 51%, range: 32–70%, TIPS procedure in 14 studies; 18.50%, range: 14–53%, and combined procedures in 16 studies; 55.50%, range: 31– 79%). BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome, TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

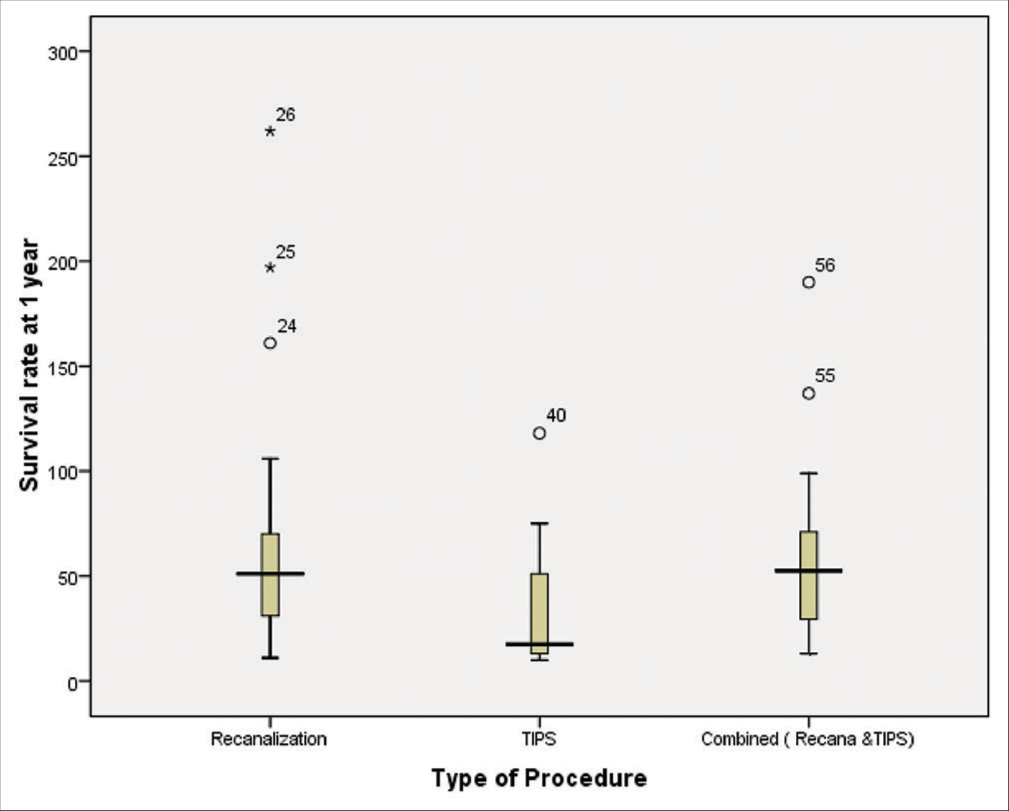

Survival rate at 1 year in different types of interventional endovascular procedures

The total survival rate at 1 year of endovascular treatment in 56 studies was 96.9%, whereas the median survival rate at 1 year of recanalization was 51% (range: 31‒70%) in 26 studies treated with angioplasty with or without stent placement. Similarly, the median survival rate at 1 year of combined procedures was 52.50% (range: 29–71%) in 16 studies using angioplasty, stent, and TIPS; and 17.50% (range: 13–51%) in 14 studies using TIPS [Figure 3].

- Box plot of median survival at 1 year different type of endovascular treatment in BCS (recanalization procedure in 26 studies; 51%, range: 31–70%, TIPS procedure in 14 studies; 17.50%, range: 13–51%, and combined procedures in 16 studies; 52.50%, range: 29–71%). BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome, TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

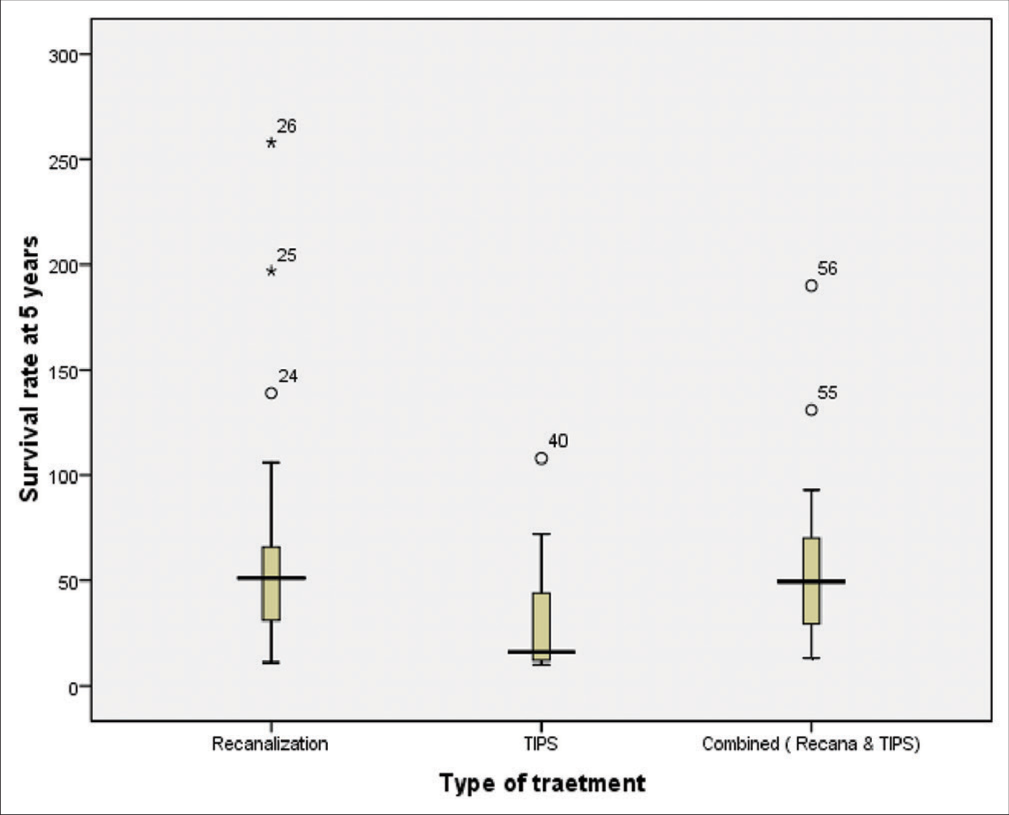

Survival rate at 5 years in different types of interventional endovascular procedures

The total survival rate at 5 years of endovascular treatment in 56 studies was 93.3%, whereas the median survival rate at 5 years of recanalization was 51% (range: 31‒66%) in 26 studies treated with angioplasty with or without stent placement. Similarly, the median survival rate at 5 years of combined procedures was 49.50% (range: 29–70%) in 16 studies using recanalization (angioplasty, stent) and TIPS; and 16% (range: 12–44%) in 14 studies using TIPS [Figure 4].

- Box plot of median survival at 5 years different type of endovascular treatment in BCS (recanalization procedure in 26 studies; 51%, range: 31–66%, TIPS procedure in 14 studies; 16%, range: 12–44%, and combined procedures in 16 studies; 49%, range: 29–70%). BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome, TIPS: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Year of publication survival rate at 1 year

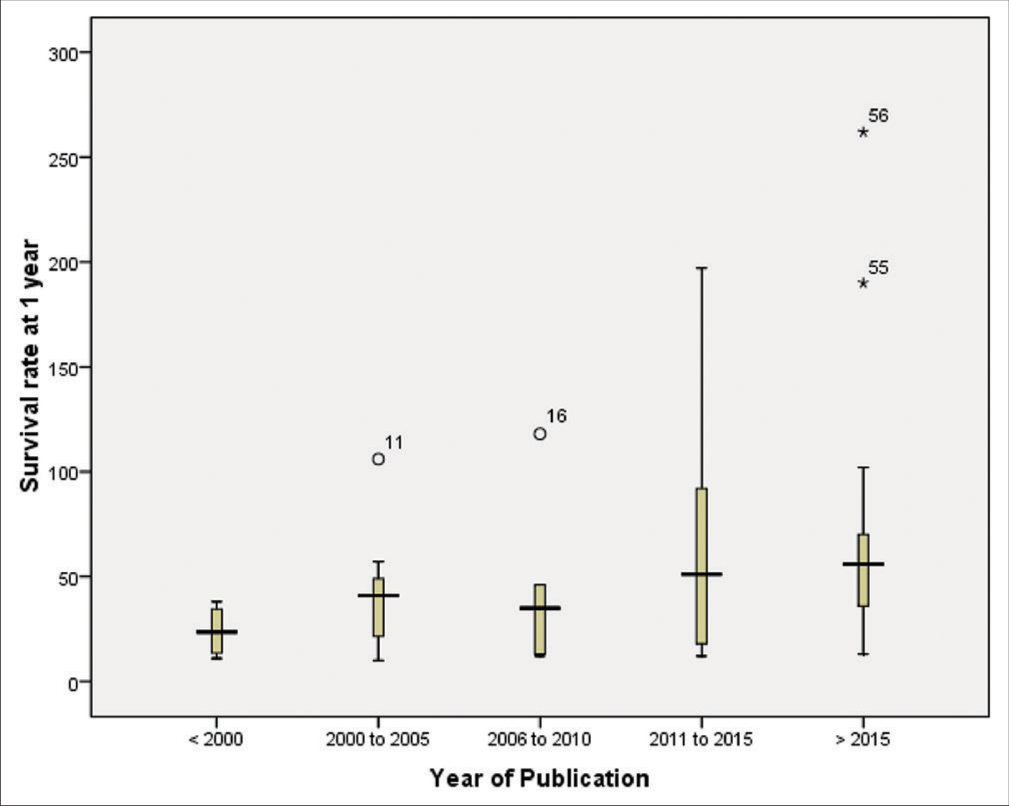

We noted that the rate of survival had increased progressively in recent studies. The median survival rate at 1 year was 23.50% (range: 13‒34%) in four studies published before 2000 and 41% (range: 21–49%) in seven studies published between 2000 and 2005. Similarly, the median survival rate at 1 year was 35% (range: 13‒46%) in five studies published between 2006 and 2010 and 51% (range: 18‒92%) in 18 studies published between 2011 and 2015. The highest median survival rate, 56% (range: 36‒70%) was noted in studies published after 2015 [Figure 5].

- Box plot of median survival at 1 year according to year of publication in endovascular treatment of BCS (<2000 = 23.50%, range: 13–34%; 2000–2005 = 41%, range: 21–49%; 2006–2010 = 35%, range: 13–46%; 2011–2015 = 51%, range: 18–92%; and >2015 = 56%, range: 36–70%). BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome.

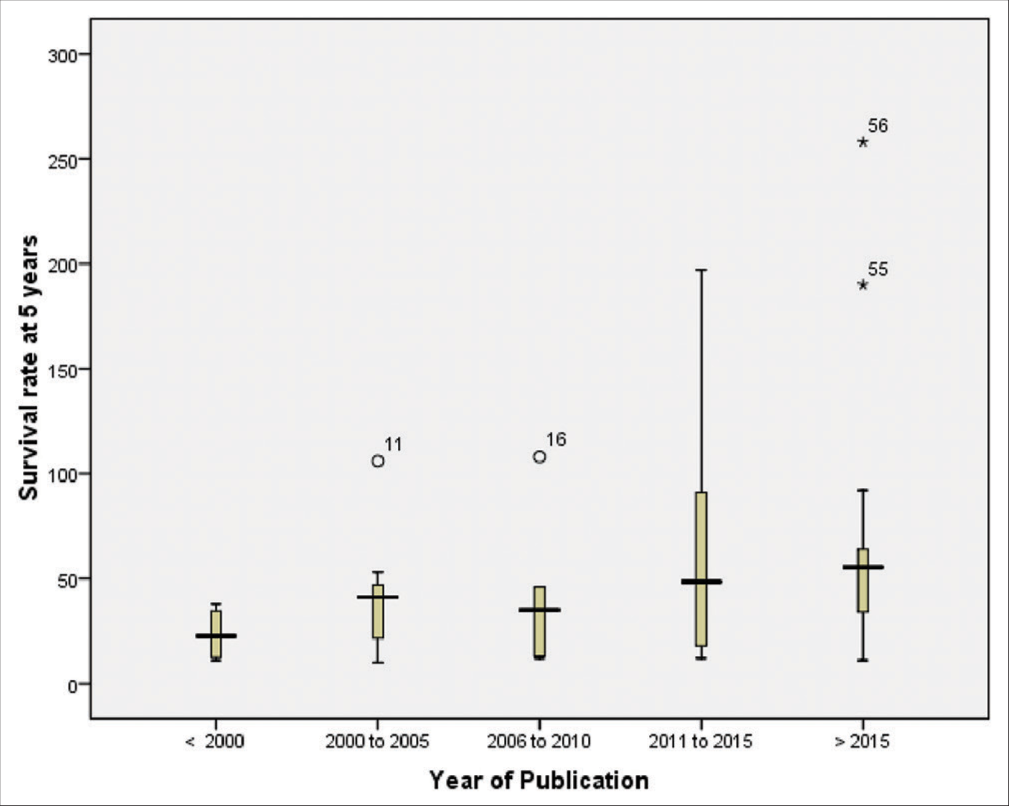

Year of publication survival rate at 5 years

The median survival rate at 5 years was 22.50% (range: 12.5–34.5%) in four studies published before 2000, 41% (range: 21.5–47%) in seven studies published between 2000 and 2005, and 35% (range: 13–46%) in five studies published between 2006 and 2010. Similarly, the median survival rate was 48.50% (range: 18–91%) in 18 studies published between 2011 and 2015, and 55.50% (range: 34–64%) in 22 studies published after 2015 [Figure 6].

- Box plot of median survival at 5 years according to year of publication in endovascular treatment of BCS (<2000 = 22.50%, range: 12.5–34.5%; 2000–2005 = 41%, range: 21.5–47%; 2006–2010 = 35%, range: 13–46%; 2011–2015 = 48.50%, range: 18–91%; and >2015 = 55.50%, range: 34–64%). BCS: Budd-Chiari syndrome.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to present the survival rate and clinical success of different types of endovascular interventional procedures in BCS. We found that most patients with BCS were treated with recanalization rather than the TIPS procedure, our results also indicating that recanalization is more common with a better survival rate. In addition, due to the high rate of shunt dysfunction, re-intervention was more common in the TIPS procedure than in recanalization.[8,28,34,38,40] However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously, as the range of the survival rate overlapped among different methods of endovascular treatment among individual studies.

The overall clinical success rate was 93.6%, and the survival rates at 1 and 5 years were 96.9% and 93.3%, respectively, for interventional endovascular treatment of BCS in 56 studies. The median survival rates at 1 and 5 years of recanalization were 51% and 51%, respectively, which were higher than those of TIPS treatment. Recanalization is a comparatively easier and quicker procedure than TIPS, and this study indicates that recanalization is more common than TIPS. In addition, in the subgroup analysis, the survival rate based on the year of publication showed a high median survival rate published after 2015. This finding indicates that the publication survival rate has progressively increased with the development of interventional endovascular therapy in recent years.

In the past few decades, modern techniques and developments in interventional endovascular therapy have contributed to progressive improvements in clinical outcomes and decreased mortality in patients with BCS. Before 1985, the survival rate at 1 and 10 years was approximately 60–70%, far less than the moderate survival rate offered by modern endovascular treatment in patients with BCS, as reported in recent studies.[69,70] The treatment for BCS is best administered in an algorithm approach and depends on the response to the previous treatment.[42,71] Medical therapy alone has a low success rate in BCS; however, interventional endovascular therapy provides high patency with good outcomes.[72] In the Western countries, anticoagulation therapy and TIPS are the most commonly used treatment modalities for patients with BCS.[73] However, recanalization has shown promising results in Asian countries with excellent clinical outcomes and higher survival rates.[15]

HV recanalization was performed in patients with short-segment HV obstruction (<3 cm), and stenting was performed in long segment HV occlusion (>3 cm) with large collateral vein drainage.[37] HV recanalization is usually difficult for BCS patients with segmental obstruction, whereas TIPS placement has been widely used for BCS patients who fail to HV recanalization.[40,74]

Recanalization restoring the physiological hepatic blood flow in liver [35,40] whereas, TIPS reduce portal venous pressure resulting in decrease symptoms by physiological modification of hepatic venous flow in the patients of BCS.[75] Recanalization can minimize the risk of hepatic encephalopathy and remains a first-line treatment option in patients with BCS.[11,12] However, TIPS has less portal vein blood perfusion in the liver with patients of BCS than recanalization and a high risk of hepatic encephalopathy due to the formation of a blood ammonia level and impaired liver function after shunt placement.[46]

In BCS, one-third of short-length stenosis was treated with recanalization by PTA with or without stent placement.[13,14,55] Tripathi et al. followed the long-term outcome of recanalization in 63 patients with BCS[55] and compared it with previously reported 59 BCS patients treated with TIPS.[42] The survival rates for recanalization at 1, 5, and 10 years were 97%, 89%, and 85%, respectively, which were comparable to the survival rates for TIPS. However, procedural complications and hepatic encephalopathy were significantly different (9.5% vs. 27.1%) and (0% vs. 18%), respectively.

In the past two decades, TIPS has been successfully used to treat BCS patients with a long-term survival rate.[10,76] Recently, an increasing number of patients with BCS have been managed using TIPS procedure.[77] The common indications for TIPS in patients with BCS include obstruction of all three HVs, refractory ascites, diffuse HV obstruction, portal hypertension, failed PTA, and occurrence of technical and clinical difficult to maintain long-term HV outcome patency.[78] Several previous studies have shown that TIPS can increase the survival rate in patients with BCS.[21-23,79] Qi et al. systematically reviewed the role of TIPS in the treatment of BCS and showed that the survival rates at 1 year and 5 years were 80–100% and 74–78%, respectively.[79] Similarly, another study examining the outcomes of interventional treatment in BCS[14] demonstrated that the survival rate of the TIPS at 1 and 5 years was 87% and 72%, and the survival rates of recanalization at 1 and 5 years were 96% and 89%, respectively. The authors also claimed that BCS patients treated with recanalization had a better survival rate than those treated using the TIPS procedure.[14] In the current systematic review, the survival rates at 1 and 5 years of recanalization were 98.5% and 95.3%, and the survival rates at 1 and 5 years for TIPS were 93.5% and 86.4%, respectively. Compared to the previous studies, our results showed a progressive increase in the survival rate.[14]

This systematic review has several limitations. First, several relevant full articles were excluded due to different analysis results and missing long-term follow-up records. Second, in the available studies, the number of patients treated using the TIPS procedure was lower than those treated with recanalization procedures. Third, the survival rate in combined (recanalization, stent, and TIPS) studies was not recorded separately. Fourth, during subgroup analysis of survival rate, a scattered distribution was observed for the year of publication. However, we noted a rapid increase in the median survival rate in studies published after 2015.

CONCLUSION

Our findings suggest that the median survival rate at 1 and 5 years of recanalization treatment is higher than that of TIPS treatment, and recanalization provides better clinical improvement. The publication year findings strongly suggest progressive improvement in intervention endovascular therapy for BCS. Thus, interventional therapy restoring the physiologic hepatic venous outflow of the liver can be considered as the treatment of choice for patients with BCS, which is a physiological modification procedure.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Budd-Chiari syndrome/hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction. Hepatol Int. 2018;12(Suppl 1):168-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inferior vena cava thrombosis at its hepatic portion (obliterative hepatocavopathy) Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22:15-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic Budd-Chiari syndrome due to obstruction of the intrahepatic portion of the inferior vena cava. Gut. 1972;13:372-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of hepatic venous outflow obstruction. Lancet. 1993;342:718-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etiology, management, and outcome of the Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:167-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: Long term success via hepatic decompression using transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered nitinol stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation: 3-year experience. Radiology. 2004;231:820-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Budd-Chiari syndrome: Outcome after treatment with the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Surgery. 2004;135:394-403.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment for hepatic vein-type Budd-Chiari syndrome: Effectiveness and long-term outcome. Radiol Med. 2018;123:799-807.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of endovascular interventional therapy for primary Budd-Chiari syndrome caused by hepatic venous obstruction. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16:4141-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous recanalization for hepatic vein-type Budd-Chiari syndrome: Long-term patency and survival. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:363-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The outcomes of interventional treatment for Budd-Chiari syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:601-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Review article: The aetiology of primary Budd-Chiari syndrome-differences between the West and China. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:1152-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu. EASL Clinical practice guidelines: Vascular diseases of the liver. J Hepatol. 2016;64:179-202.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: A single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16236-44.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical spectrum, investigations and treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome. QJM. 1996;89:37-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment of symptomatic Budd-Chiari syndrome-in favour of early transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:656-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good clinical outcomes following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stentshunts in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:864-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long term survival of patients undergoing TIPS in Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;9:56-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome and analysis of dysfunction of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement in chronic primary Budd-Chiari syndrome. Radiology. 2017;283:280-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcomes of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in Indian patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1174-82.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome of a covered vs. uncovered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver Int. 2008;28:249-56.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The utility of TIPS in the management of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Ann Surg. 2005;241:978-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIPS for Budd-Chiari syndrome: Long-term results and prognostics factors in 124 patients. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:808-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome patients: Results from a single center. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2014;37:691-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with a focus on transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. World J Hepatol. 2013;5:38-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) Radiol Med. 2008;113:727.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome in children: Clinical features, percutaneous radiological intervention, and outcome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1030-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: Long-term effect on outcome with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Gastroenterol hepatol. 2005;20:1494-502.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: Outcomes of endovascular intervention-A single-center experience. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2017;36:209-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing spectrum of Budd-Chiari syndrome in India with special reference to non-surgical treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:278-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early radiological intervention and haematology screening is associated with excellent outcomes in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1361-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of percutaneous transhepatic interventional treatment for symptomatic Budd-Chiari syndrome secondary to hepatic venous obstruction. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2013;1:392-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular management of Budd-Chiari syndrome with inferior vena cava thrombosis: A 14-Year single-center retrospective report of 55 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;27:1592-603.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome: Single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:237-43.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excellent long-term outcomes of endovascular treatment in Budd-Chiari syndrome with hepatic veins involvement: A STROBE-compliant article. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12944.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of different radiological interventional treatments of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2015;46:1011-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Favourable medium term outcome following hepatic vein recanalisation and/or transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for Budd Chiari syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:878-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good clinical outcomes in Budd-Chiari syndrome with hepatic vein occlusion. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:3054-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good long-term outcome of Budd-Chiari syndrome with a step-wise management. Hepatology. 2013;57:1962-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome of recoverable stents for Budd-Chiari syndrome complicated with inferior vena cava thrombosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7393.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of intravascular intervention in the management of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2659-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An individualised strategy and long-term outcomes of endovascular treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome complicated by inferior vena cava thrombosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55:545-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome caused by obstruction of the hepatic inferior vena cava: Immediate and 2-year treatment results of transluminal angioplasty and metallic stent placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:32-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: Characteristic and long-term outcomes of endovascular treatment. Vascular. 2017;25:642-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catheter aspiration with recanalization for Budd-Chiari syndrome with inferior vena cava thrombosis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2019;29:304-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of long-term outcomes of endovascular management for membranous and segmental inferior vena cava obstruction in patients with primary Budd-Chiari syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003104.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with hepatic vein obstruction in China. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2014;24:846-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inferior vena cava obstruction: Long-term results of endovascular management. Indian Heart J. 2012;64:162-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interventional endovascular treatment for Budd-Chiari syndrome with long-term follow-up. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:318-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcomes of endoluminal sharp recanalization of occluded inferior vena cava in Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2019;29:309-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term effect of stent placement in 115 patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2587-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcomes following percutaneous hepatic vein recanalization for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Liver Int. 2017;37:111-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term safety and outcome of percutaneous transhepatic venous balloon angioplasty for Budd-Chiari syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:222-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Necessity and indications of invasive treatment for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:254-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness and postoperative prognosis of using preopening and staged percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the inferior vena cava in treating Budd-Chiari syndrome accompanied with inferior vena cava thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2019;60:52-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous balloon angioplasty of inferior vena cava in Budd-Chiari syndrome-R1. Int J Cardiol. 2002;83:175-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous recanalization for Budd-Chiari syndrome: An 11-year retrospective study on patency and survival in 177 Chinese patients from a single center. Radiology. 2013;266:657-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous recanalization for combined-type Budd-Chiari syndrome: Strategy and long-term outcome. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:3240-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome with inferior vena cava thrombosis. Exp Ther Med. 2013;5:1254-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Use of accessory hepatic vein intervention in the treatment of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2015;38:1508-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for complete membranous obstruction of suprahepatic inferior vena cava: Long-term results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2016;39:1392-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous sonographic guidance for TIPS in Budd-Chiari syndrome: Direct simultaneous puncture of the portal vein and inferior vena cava. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:560-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radiological intervention in Budd-Chiari syndrome: Techniques and outcome in 18 patients. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:775-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment by percutaneous balloon angioplasty of Budd-Chiari syndrome caused by membranous obstruction of inferior vena cava: 8-year follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1720-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applicability of different endovascular methods for treatment of refractory Budd-Chiari syndrome. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2011;61:453-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of Budd Chiari syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1151-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of survival and the effect of portosystemic shunting in patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hepatology. 2004;39:500-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd-Chiari syndrome: A review by an expert panel. J Hepatol. 2003;38:364-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of patients with primary hepatic venous obstruction treated with anticoagulants alone. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:8-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recanalization of occlusive transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts inaccessible to the standard transvenous approach. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:61-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An update on the management of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:1780-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIPS for acute and chronic Budd-Chiari syndrome: A single-centre experience. J Hepatol. 2003;38:751-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiming at minimal invasiveness as a therapeutic strategy for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hepatology. 2006;44:1308-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term efficacy of Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt treatment for Budd-Chiari syndrome. Hellenic J Radiol. 2017;2:12-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for Budd-Chiari syndrome: Techniques, indications and results on 51 Chinese patients from a single centre. Liver Int. 2014;34:1164-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]