Translate this page into:

Imaging of Cystic and Cyst-like Lesions of the Mediastinum with Pathologic Correlation

Address for correspondence: Prof. Kemal Ödev, Selcuk University Meram School of Medicine, Department of Radiology, 42080 Konya, Turkey. E-mail: kemalodev50@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Cystic masses of the mediastinum are a heterogenous group of asymptomatic or symptomatic, congenital, infectious, or neoplastic lesions. For early and correct diagnosis, evaluation, and optimal patient management of cystic mediastinal masses in infants, children, or adults imaging plays an important role. A non-invasive and sensitive imaging modality is an efficient and cost-effective tool. Multidetector computed tomography (MDTC) with volumetric acquisition provides fast acquisition of high resolution images and multiplanar reconstruction. Both 2D and 3D imaging in mediastinal imaging help in surgical planning and assessing resectability of mediastinal lesions. MR imaging has many advantages over other modalities for detecting and identifying cystic, or fluid-filled mediastinal masses, because of its intrinsic high soft tissue contrast and direct multiplanar imaging capabilities. However, histological tissue analysis may be required to differentiate a cystic lesion from other cyst-like or low-attenuation lesions.

Keywords

Cysts

computed tomography

mediastinum

magnetic resonance imaging

radiograph

INTRODUCTION

Most of the mediastinal cystic masses do not cause symptom and often present as asymptomatic mediastinal masses. However, they may occasionally cause symptoms that are secondary resulting from compression of adjacent organs. Mediastinal cystic lesions represent 15%-20% of all mediastinal masses.[1–3] Most of them originate from abnormal development of the embryo. They occur in all mediastinal compartments (anterior, middle, and posterior) of the mediastinum. Congenital mediastinal cysts include foregut, pericardial, and thymic cysts. Foregut cysts may be classified as bronchogenic, esophageal duplication, and neurenteric cysts.[1–3] Chest radiograph is usually the first diagnostic imaging modality for evaluation of mediastinal masses.[2] When compared with single-detector helical CT, multidetector CT (MDTC) offers many advantages in the evaluation of suspected mediastinal lesions and focal mediastinal widening.[45] Because of the improvement in spatial temporal and contrast resolution of the MDCT images, the diagnostic accuracy of CT has been improved when compared with MR imaging.[56] However, sagittal or coronal MR images can provide anatomic information that the transaxial CT or MR images cannot provide.[7] In this article, we review the imaging features of cystic and cyst-like mediastinal lesions according to CT and MRI findings.

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Foregut cysts

Mediastinal cysts of foregut origin constitute up to 9% of all primary mediastinal masses. Mediastinal cysts result from embryologic aberrations and develop on abnormal budding of the primitive foregut and early tracheobronchial tree.[289] The spectrum of foregut cysts includes bronchogenic cysts, esophageal duplication cysts, and neurenteric cysts.[89]

Bronchogenic cysts

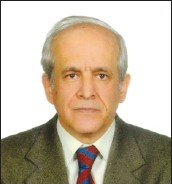

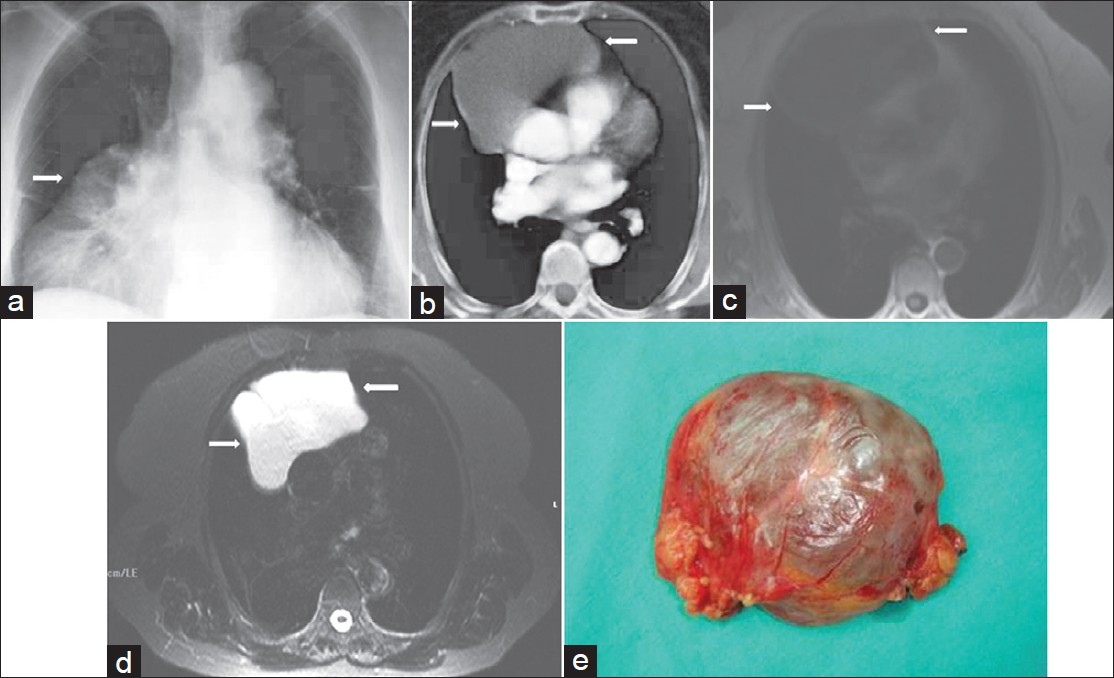

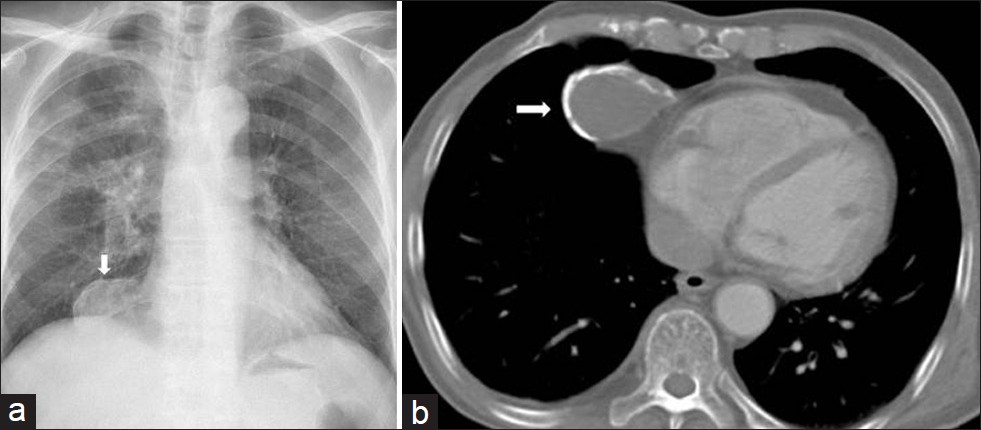

Bronchogenic cysts can be located in the carinal area, paratracheal area, esophageal wall, and retrocardiac area.[238] They may occur rarely within the parenchyma, pleura, or diaphragm.[10] Bronchogenic cysts often present as asymptomatic mediastinal masses. When symptoms are present, they are likely to be related to the effect of the mass on the surrounding structures, such as bronchi, esophagus, or mediastinal vessels.[310] On CT, a bronchogenic cyst appears as a single, smooth, round, or elliptic mass with well-defined, thin, smooth wall and non-enhancing homogenous cystic mass [Figure 1]. This feature suggests that the lesion is a cyst. However, a thick or irregular wall is not a typical feature of bronchogenic cyst and suggests necrotic neoplasm or lymphadenopathy. Half of the lesions have the same density as water and the others have a CT density which varies depending on the cystic component.[2310] Occasionally, bronchogenic cysts show a much higher density than that of water. This increased density is a result of the presence of calcium, proteinaceous fluid, mucus, and/or blood debris within the cyst.[239] On MRI, bronchogenic cysts frequently show signal intensity higher than that of muscle on T1-weighted images [Figure 1]. However, T1-weighted MRI may show variable patterns of signal intensity because of variable cystic contents and presence of protein, hemorrhage, or mucoid material.[23] On T2-weighted MRI, cysts show high signal intensity, suggesting a cystic lesion [Figure 1]. On rare occasion, cyst may show a fluid–fluid level[23] and calcification located peripherally in the cyst wall.[310]

- Bronchogenic cyst in an asymptomatic 50-year-old man. (a) Chest radiograph shows a sharply defined lesion of increased opacity in the right cardiophrenic angle (arrow). (b) Contrast enhanced CT shows a well -circumscribed low- attenuation lesion in the posterior mediastinum.Note posterior mediastinal mass extending into the azygoesophageal recess and pericardium. (c) Axial T1-weighted MR image shows a lesion (M) of increased signal intensity compared to CSF. (d) Axial T2- weighted MR image reveals that the lesion is of similar signal intensity as that of CSF, which suggests a cyst. The cyst capsule is seen as a well-defined low-signal intensity rim (arrow) on T2-weighted MR image. The cystic lesion exhibits septations or mural nodules. (e) Photograph of the cystic lesion.

Duplication cysts

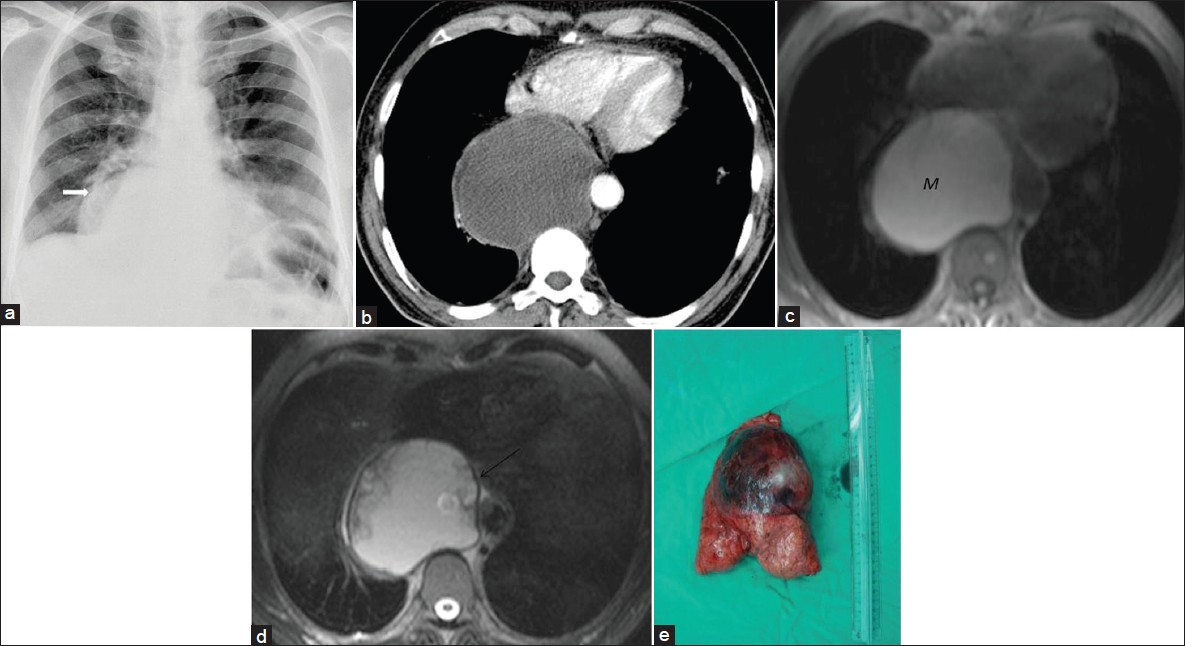

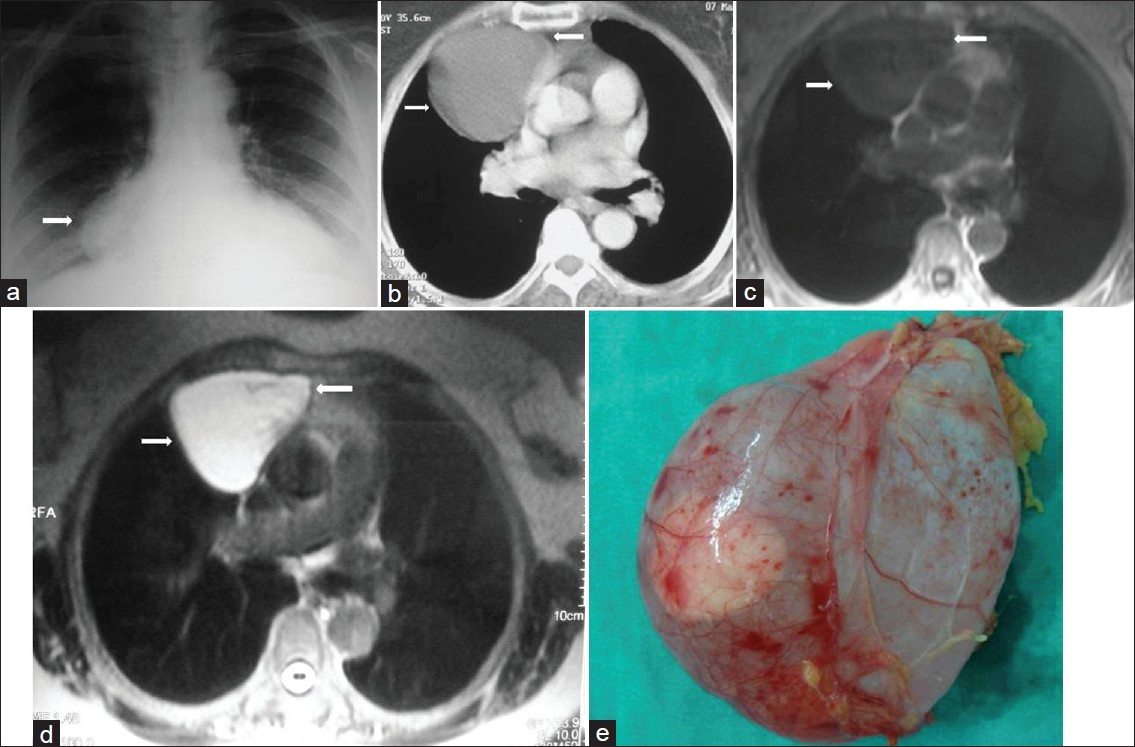

Majority of esophageal duplication cysts occur in infants or children. In upto 60% of patients they are usually located adjacent to or within the esophageal wall in the lower posterior mediastinum.[38] Ectopic gastric mucosa in the cyst may cause hemorrhage or perforation of the cyst or infection.[38] CT or MRI features of duplication cysts are similar to those of bronchogenic cysts [Figure 2], except for their location which is usually close to the eosophagus and within its wall.[23911]

- Esophageal duplication cyst in a 3-year-old girl with cough and dyspnea. (a) Chest radiograph shows homogenous opacification of the right hemithorax (arrows) at the time of first admission. (b) Follow-up CT scan 3 years later shows a large cystic periesophageal mass (arrows) . Diagnosis was confirmed at surgery.

Neurenteric cysts

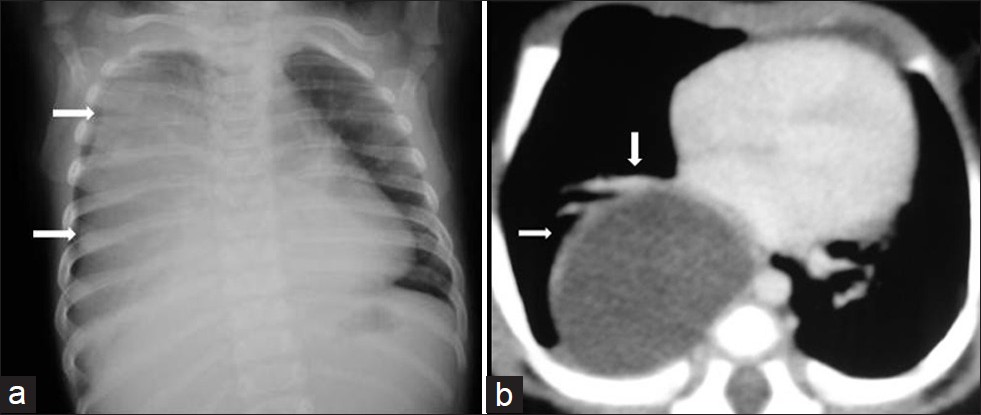

Neurenteric cysts are rare posterior mediastinal lesions that may be connected to the meninges through a midline defect in one or more vertebral bodies. This abnormality may be associated with vertebral anomalies, such as hemivertebrae, butterfly vertebra, or spina bifida.[212] Enteric cysts are usually single, smooth, and unilocular. They occur primarily in the lower cervical and thoracic regions. The fluid within the cyst may be nearly identical to CSF or may be milky, cream-colored, yellowish, or xanthochromic. Enteric cysts are usually intradural, extramedullary, and situated ventral or ventrolateral to the spinal cord.[12] CT shows vertebral anomalies in about 50% of affected patients. However, MRI shows most of the vertebral anomalies, and more importantly, allows the accurate assessment of tumor extention into the spinal canal and the relationship of cystic lesions with the spinal cord [Figure 3].[12]

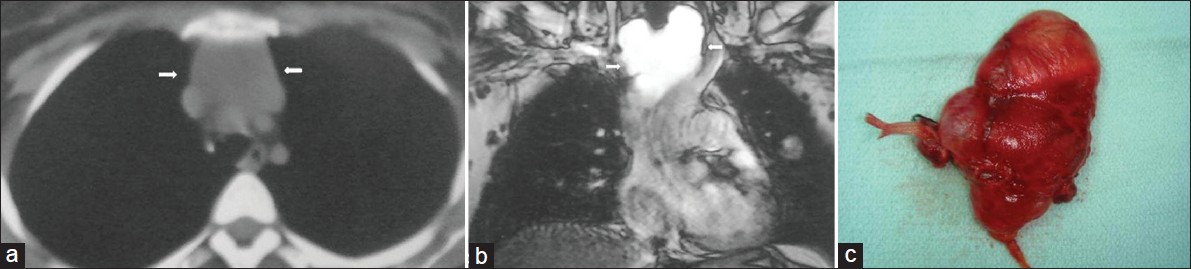

- Neurenteric cyst in a 30-year-old female with flank pain. (a) Chest radiograph shows a well-defined round mass (arrow) in the lower thoracic region. (b- c) Both axial T1-weighted – and coronal T2-weighted MR images show a large mass that is of homogenous high signal intensity in the right paravertebral region (arrow). The cyst presumably contains proteinaceous fluid. (d) The photograph of the resected tumor shows a thick-walled encapsulated cystic mass.

CONGENITAL OR ACQUIRED MEDIASTINAL MASSES

Pericardial cyst

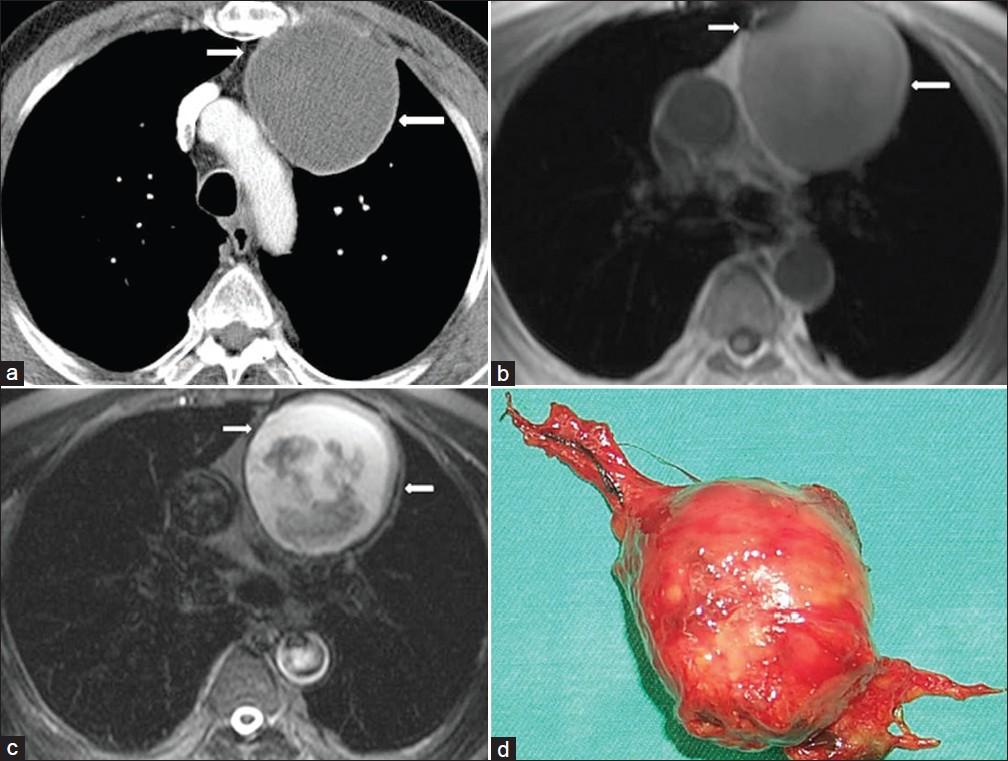

Pericardial or mesothelial cysts result from aberrations in the formation of coelomic (somatic) cavities and are uncommon benign congenital anomalies.[13] On chest radiograph, these cysts appear as well-defined, round, or oval masses either left or right of the cardiophrenic angle, although they may be present in the upper mediastinum. Most pericardial cysts are unilocular [Figure 4]. The cysts are rarely connected to the pericardium.[313] CT and MRI features are similar to those of other congenital mediastinal cysts [Figure 4].[3]

- Pericardial cyst in a 40-year-old man with chest pain. (a) Chest radiograph shows a mass causing apparent enlargement of the right heart border. (arrow) (b) Contrast enhanced CT shows a well-circumscribed low-attenuation mass in the right cardiophrenic angle (arrows). (c) Axial T1-weighted MR image shows a round low-signal intensity lesion (arrows) in the right cardiophrenic angle. (d) T2-weighted fat- supressed MR image shows that the lesion (arrows) is of similar signal intensity as that of CSF, which suggests a cyst. (e) Photograph shows a cystic mass.

Pericardial diverticulum

Pericardial diverticulum may be either congenital or acquired. A diverticulum of the pericardium may develop secondary to cardiac disease and pericardial effusion. Most patients are asymptomatic. Most of these lesions are found incidentally at autopsy or during an operation.[14] On chest radiograph, these cysts may simulate cardiac or aortic aneurysm , vascular anomalies, cardiac and pericardial tumors, and medastinal cystic masses.[14] Majority of the pericardial diverticulum are located either left or the right of the cardiophrenic angle.[13] Unusual locations include the superior mediastinum, aortic arch, and left hilum.[13] On chest radiograph, this abnormality appears as a smooth, rounded, or ovoid, well-defined solitary mass adjacent to the cardiac counter and inseparable from that of the cardiac silhouette [Figure 5].[13] CT and MRI features are similar to those of other congenital mediastinal cysts [Figure 5].

- Pericardial diverticulum in an asymptomatic 45-year-old man. (a) Chest radiograph shows a mass (arrow) with smooth contour in the right cardiophrenic angle (arrow). (b) Contrast enhanced CT shows a low-attenuation mass (arrows) in the right cardiophrenic angle. (c) The mass (arrows) shows homogeneously low signal intensity on axial T1-weighted MR image and (d) high signal intensity (arrows) on T2-weighted MR image. (e) Photograph shows a translusent round cyst.

Thymic cysts

Benign thymic cysts account for approximately 3% of all anterior mediastinal masses. Such cysts can be either congenital or acquired in origin. Congenital cysts are typically unilocular. These contain clear fluid and imperceptible thin wall.[15–17] CT and MRI features are similar to those of other congenital mediastinal cysts [Figure 6]. If hemorrhage or infection occurs, the cyst may show high signal intensity on both T1 and T2 weighted images.[3] Multilocular thymic cysts are acquired lesions of the thymus and acquired thymic cysts result from an inflammatory process. They are usually multilocular.[16] True multilocular thymic cysts can occur in association with thymic neoplasias, including thymoma and thymic carcinoma.[15]

- Thymic cyst in a 60-year-old asymptomatic male with a history of coronary artery by-pass surgery. (a) Contrast enhanced CT shows inhomogenous unilocular low-attenuation mass (arrows) in the anterior mediastinum, (b) Axial T1-weighted MR image shows a well-circumscribed mass with heterogenous signal intensity in the anterior mediastinum (arrows). (c) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a high signal intensity unilocular cystic mass (arrows). There are some areas of low signal intensity corresponding to the small debris materials. Needle biopsy was performed. Microscopic examination revealed a thymic cyst containing cellular keratinous material. (d) Specimen shows a cystic mass.

CYST-LIKE OR LOW-ATTENUATION MEDIASTINAL MASSES

Meningocele

Intra-thoracic or laterale thoracic meningocele is a CSF-filled protrusion of the leptomeninges through an intervertebral foramen or a defect in the vertebral body. Lateral meningoceles are most common in patients with mesenchymal disorders such as neurofibromatosis (85%), Marfan's and Ehler-Danlos syndromes.[318] The lesion is seen on CT and MRI images as a paravertebral oval mass with homogenous signal intensity and or an attenuation typical to that of CSF which communicates via a neural foramen with the subarachnoid space.[13] Other radiological findings may include erosion of the vertebral bodies, rib anomalies, and enlarged intervertebral foramina due to mass effect.[13]

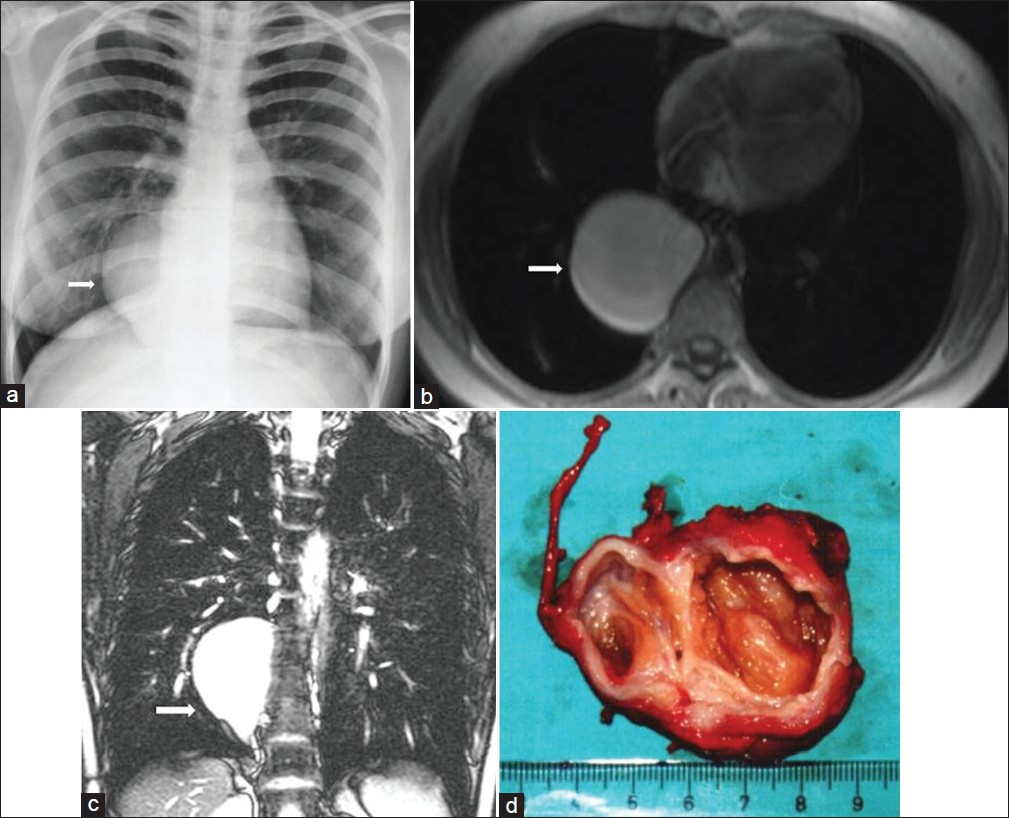

Mature cystic teratoma

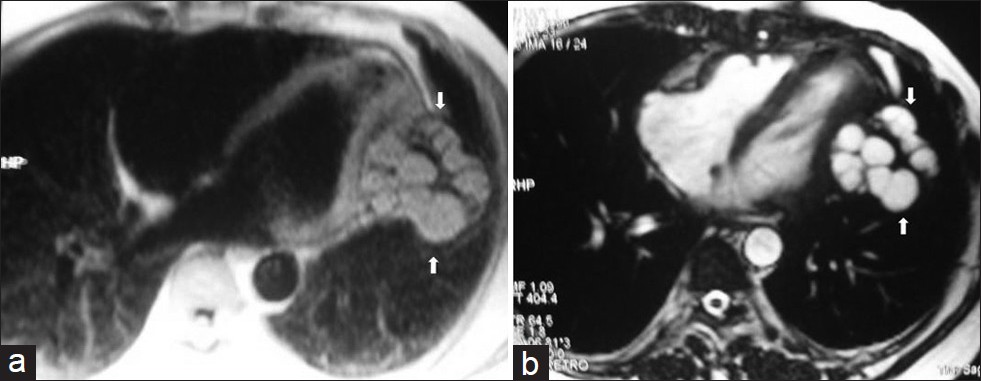

Mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cyst) of the mediastinum are tumors that contain ectodermal, mesodermal, and endodermal derivates.[319] The cysts are filled with sebaceous material and may contain hair. Although patients are usually asymptomatic, large tumors may cause chest pain, dyspnea, and cough. Majority of dermoid cysts are in the anterior mediastinum. However, approximately 3-8% of the lesion occur in the posterior mediastinum.[319] Chest radiograph shows a large anterior mediastinal mass that extends to one side of the midline.[320] On CT the combination of multiple-tissue elements within a cystic mediastinal mass suggest the diagnosis of mature teratoma [Figure 7].[20] Fatty and cystic components are present in half of the cases, and sometimes a fat-fluid level within the mass strongly suggests the diagnosis.[23] MRI may directly demonstrate a heterogenous mediastinal mass containing a variable mixture of fat, fluid, soft tissue, and calcification [Figure 7]. Rupture of the cystic tumor into the pleura or pericardial space is a rare complication causing clinical symptoms.[20]

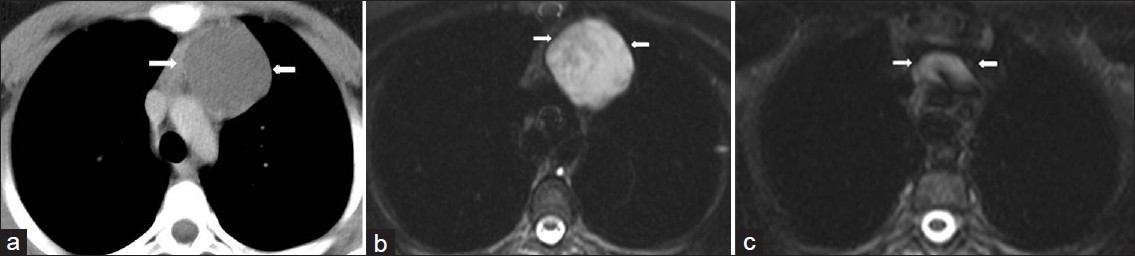

- Mature cystic teratoma in a 20-year-old female who had chest pain and dyspnea. (a) Contrast enhanced CT shows a heterogeneous mediastinal mass with fat-containing areas (arrows). (b) Coronal T1-weighed MR image shows a mass with low signal intensity and areas of fat with high signal intensity (arrows). (c) On T2-weighted MR image, the mass shows a multilocular appearance with high signal intensity (arrows). (d) T2-weighted fat-suppressed MR image shows that the mass contains a high signal intensity of multilocular cystic mass and nodular areas with low signal intensity (arrows). (e) Photograph of the specimen.

Lymphangioma

The origin of lymphangiomas is controversial. They may be developmental, hamartomatous, or neoplastic.[2122] Approximately 90% of all lymphangiomas manifest as a mass in the neck or axilla in patients less than 2 years old.[21] They are subdivided histologically as simple (capillary) cavernous or cystic (hygroma), depending on the size of the lymphatic channels that they contain. On chest radiograph lymphangiomas appear as well-defined lobulated mass. Unilateral or bilateral pleural effusion, which is often chylous, may be present. On CT, the lesions usually show a smooth lobulated mass, which may envelop adjacent structures without displacement or with displacement of major mediastinal vessels. Lymphangiomas usually have homogenous low attenuation similar to that of water [Figure 8]. When attenuation of the cystic mass is slightly higher than that of water, this may represent elevated protein content in the fluid or combination of fluid, solid tissue, and fat.[321] On MRI, the lesion has a signal similar to or greater than that of muscle in T1-weighted images [Figure 8].[21]

- Lymphangioma in an asymptomatic 30-year-old female. (a) Contrast enhanced CT shows a low- attenuation mass (arrows). (b) Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows a high signal intesity cystic mass (arrows) in the upper mediastinum. (c) Photograph of the cystic lesion.

Nerve sheath tumors - cystic schwannoma

Neural tumors can be divided into nerve sheath tumors, ganglion cell tumors, and paraganglionic cell tumors.[29] The nerve sheath tumors comprise schwannomas, neurofibromas, and other malignant forms. Most neurogenic tumors occur in the paravertebral areas of the intercostal and sympathetic nerves. Enlargement of neural foramina or pressure erosion of adjacent rib is not uncommon.[9] On CT, schwannoma appears as a well-defined, smooth, rounded, lobulated, or grossly encapsulated mass in the paravertebral region [Figure 9][23] or along the course of intercostal nerves. On CT scan, schwannoma may manifest as a low-attenuation or low-density mass. These findings may be related pathologically to high amounts of lipids and interstitial fluid (especially in Antony type B schwannoma) in the neural tissue, and cystic degeneration due to vascular thrombosis and subsequent necrosis.[2324] Benign schwannomas may have variable inhomogenous signal intensity and low signal intensity areas due to necrotic component. Thus, they may have low to intermediate signal intensity in T1 weighted MR images, and inhomogenous high signal intensity throughout the lesion in T2 weighted images [Figure 9].[324]

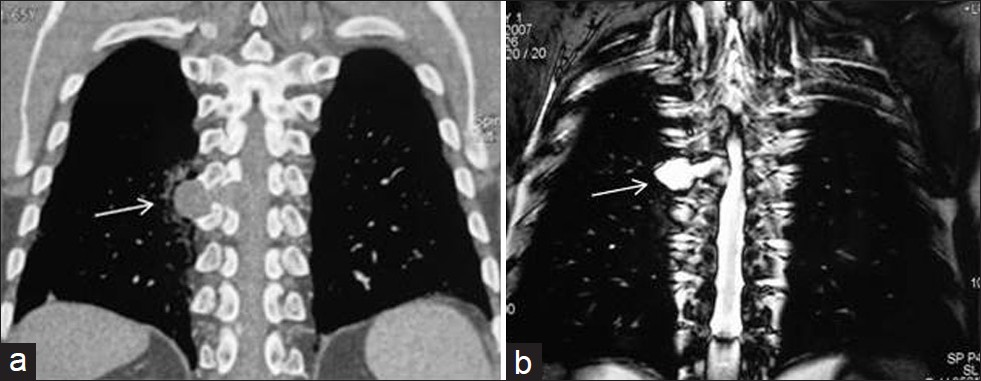

- Cystic schwannoma in a 30-year-old asymptomatic female. (a) Reformatted coronal CT shows a homogenous low-attenuation mass in the paravertebral gutter (arrow). An extension into the neural foramen is suspected suggesting a neural tumor. (b) Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows a homogenous high signal intensity cystic lesion (arrow) that is an extension into the neural foramen. Diagnosis was confirmed at surgery.

Cystic thymoma

Cystic changes in thymoma are encountered in as many as 40% of the cases and are mostly focal.[25] At times, it can be extensive and presents as an unilocular or multilocular cystic mass containing blood or yellow-brown grumose material. The tumor may be seen either as a mural nodule or as randomly scattered solid areas.[2526] Cystic thymomas should be distinguished from non-neoplastic congenital and acquired thymic cysts and other primary thymic neoplasms undergoing extensive cystic degeneration.[26] CT and MRI features are similar to these of other congenital mediastinal cysts [Figure 10].

- Recurrent cystic thymoma in a 14-year-old girl with a history of multiple resection of cystic thymic lesion. (a) Contrast enhanced CT shows a low-attenuation lesion (arrow) in the anterior mediastinum at the first admission. (b) Axial T2-weighted MR image shows a thin -walled high signal intensity cystic lesion (arrow). (c) Post surgical (4 years after surgical operation of the cystic lesion) T2-weighted MR image at the same level shows a lobulated mass (arrow) with cystic components.

Mediastinal pancreatic pseudocyst

The aggressiveness of pancreatic fluid allows extrapancreatic collection to migrate to the mediastinum. The fluid collections related to pancreatitis occur outside the gland as well. These extra-pancreatic fluid collection or pseudocyst is found most commonly in the lesser sac and uncommonly in the mediastinum [Figure 11].[927] Mediastinal pseudocyst almost always is located in the lower part of the posterior mediastinum. CT shows an encapsulated fluid collection with low attenuation in the posterior mediastinum associated with compression or displacement of esophagus or splaying of the diaphragmatic crura.[9]

- Pancreatic pseudocyst in a 40-year- old male with a 3-week history of chest-and epigastric pain. Contrast enhanced CT shows bilateral pleural effusion and periaortic fluid collection(arrow) displacing the esophagus (arrow) (This case courtesy of Aysel Türkvatan, Ankara, Turkey).

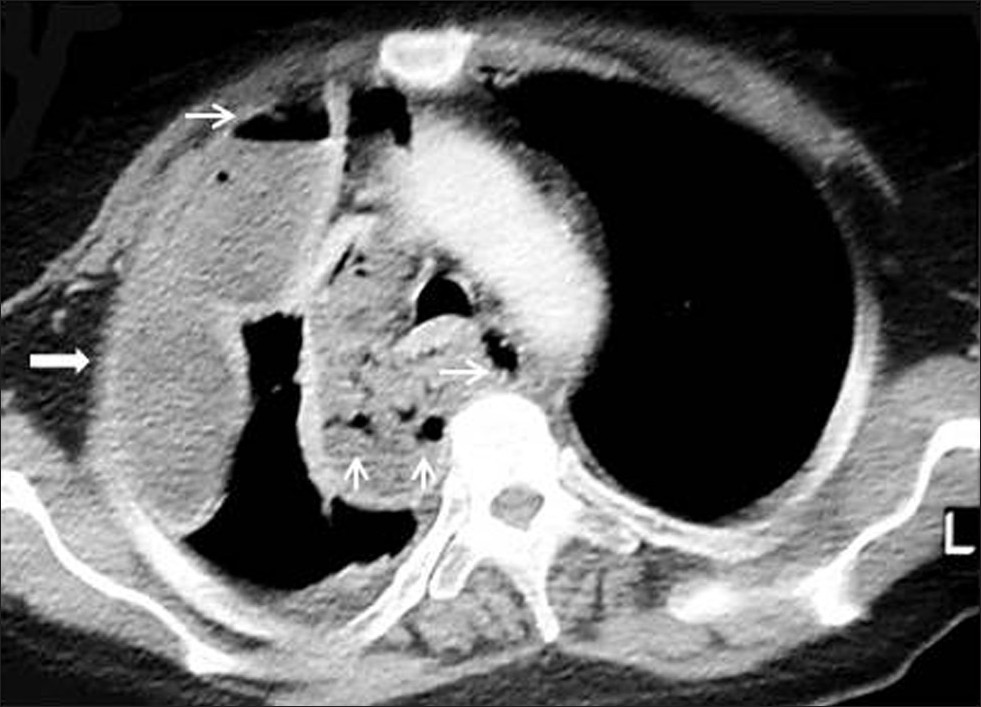

Mediastinal abscess

Mediastinal abscess is related to esophageal perforation, or post-operative infection (e.g. median sternotomy), or spread of infection from an adjacent region. Mediastinal abscess shows a low-attenuation mass surrounded by an enhancing rim. Abscess may be single, but are frequently multiple. The gas or air-fluid levels may be seen in more discrete rounded collection. Gas bubbles may be scattered through the mediastinum [Figure 12].[38] Clinical features and CT findings usually permit differentiation from cysts and subacute or chronic hematomas.[8]

- Mediastinal abscess in a 40-year-old male who had blunt trauma. Contrast enhanced CT shows a low- attenuation mass (arrow) with gas bubble (thin arrow) and loculated pleural effusion on the right.

Mediastinal angiomatosis

Angiomatosis is a rare benign vascular lesion. It represents almost 4% of vascular tumors in children and adolescents. These lesions occur most commonly in the soft tissues, chest wall, head and neck region, and abdomen.[2829] To our knowledge, this rare vascular malformation described in the literature is a fatal disorder[27] and there are very few reports of diffuse angiomatosis of mediastinum.[2930] CT and MRI features of the case described in our study are similar to those of other congenital mediastinal cysts [Figure 13]. However, radiological features of the case described in our study are different from reported in the literature. As far as we know, this is the first such case reported in the literature.

- Mediastinal angiomatosis in a 7-year-old boy with chest pain. (a) On chest radiograph, the left hemitorax is diffusely opacified (arrow). (b) Contrast enhanced CT shows a huge mass (arrow) with uniform low-attenuation of the left hemithorax with mass effect on the mediastinum. (c) Axial T1-weighted MR image shows a large low signal intensity cyst (arrow). (d) Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows that the large mass (arrow) is of homogenous high signal intensity without septation. (e) Photograph of the mass.

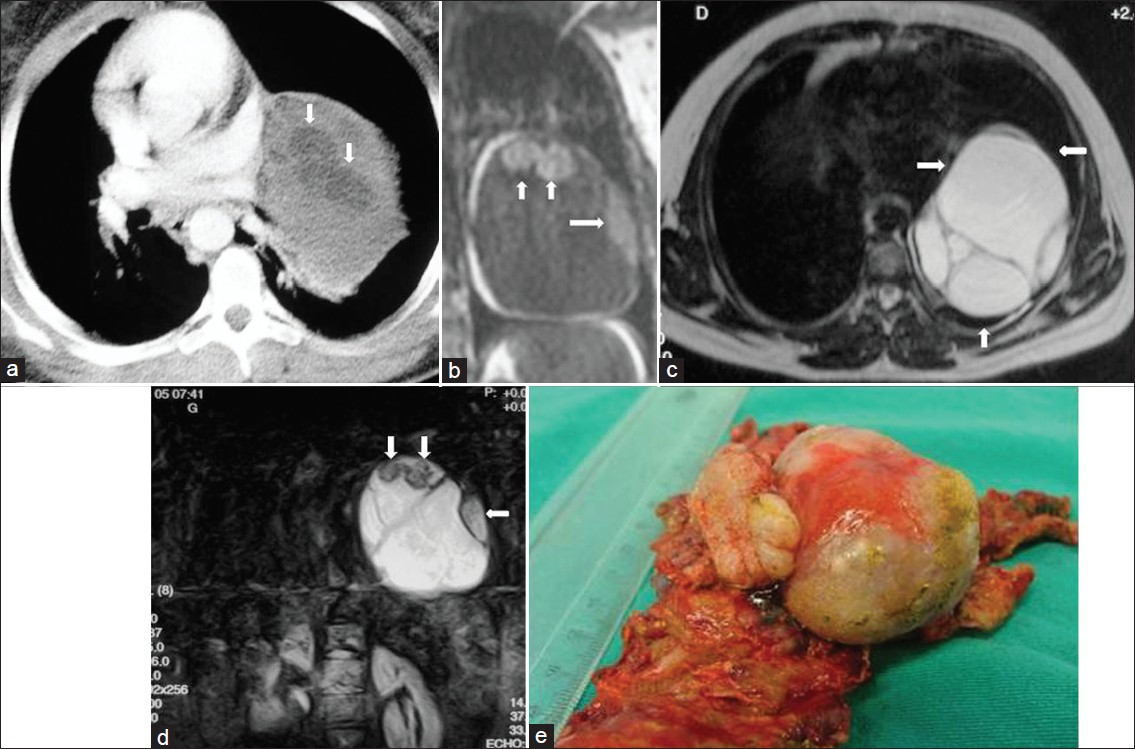

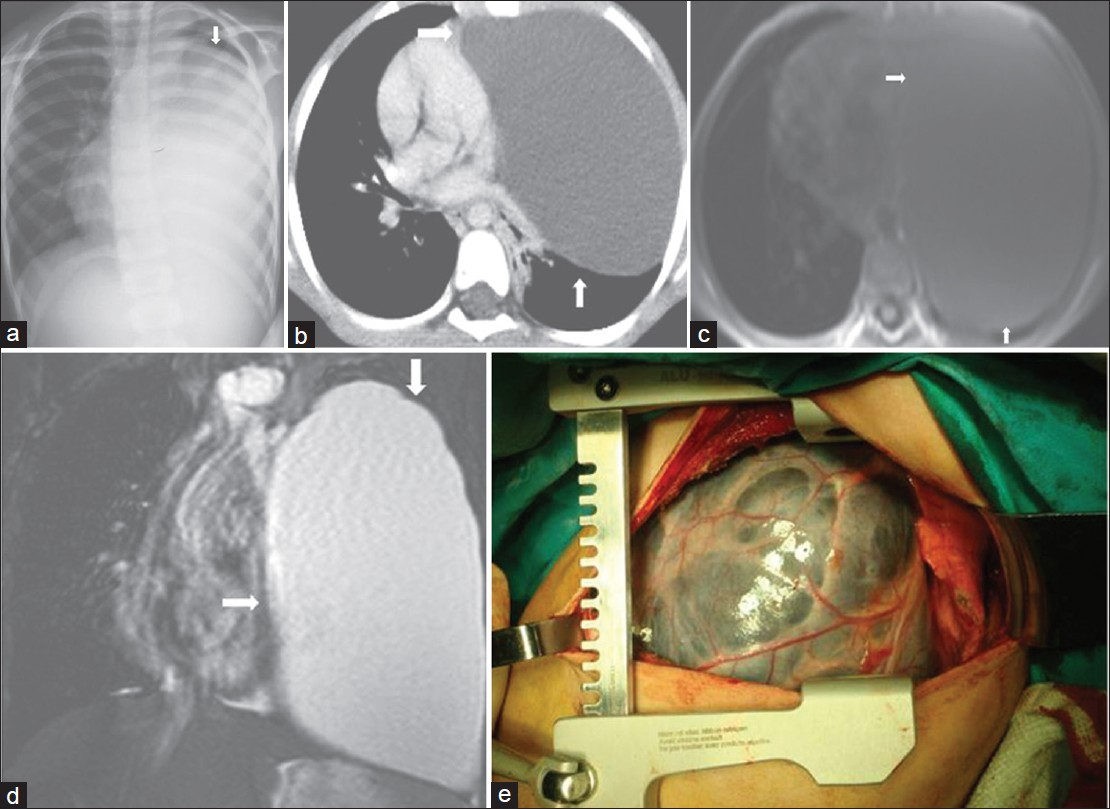

Mediastinal hydatid cyst

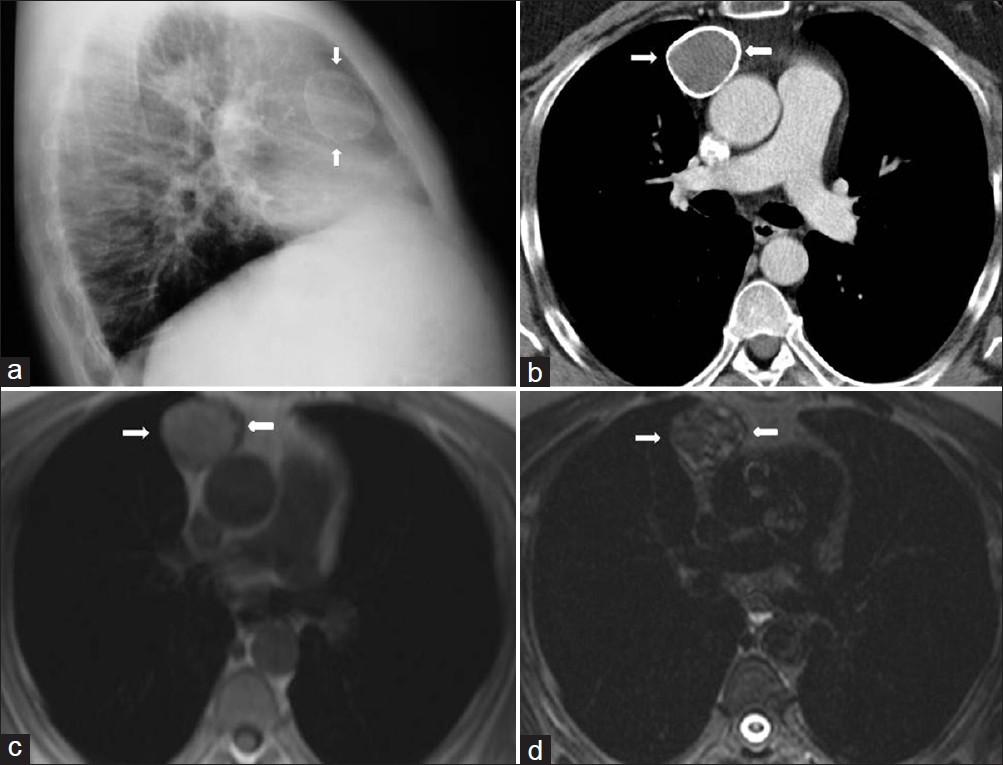

Hydatid cysts are usually located in the liver, lungs, and brain. Mediastinal hydatid cysts (MHCs) are very rare. The symptoms of MHCs depend on the size and location of the cyst and the involvement of adjacent structures.[3132] Mediastinal hydatid cysts (MHCs) occur infrequently with an incidence ranging from 0-6%.[31] Several patterns of mediastinal HCs, including the unilocular cyst [Figure 14], multivesicular cyst [Figure 15], and calcified cyst [Figure 16] have been described by using imaging techniques.[33] Unilocular MHCs may also give a CT appearance similar to that of primary mediastinal cystic masses. Characteristic findings of echinococcal cysts (e.g. floating membranes, daughter cysts, and vesicles) can usually help establish the diagnosis of HCs.[3133] CT and MR imaging are useful in the evaluation of MHCs. CT best demonstrates cyst wall calcification [Figure 16]. MR imaging has the capability of providing more information about anatomical location of MHCs. Type 2 and Type 3 HCs in the anterior mediastinum should be differentiated from cystic teratoma, thymoma, and necrotic neoplasm.[31]

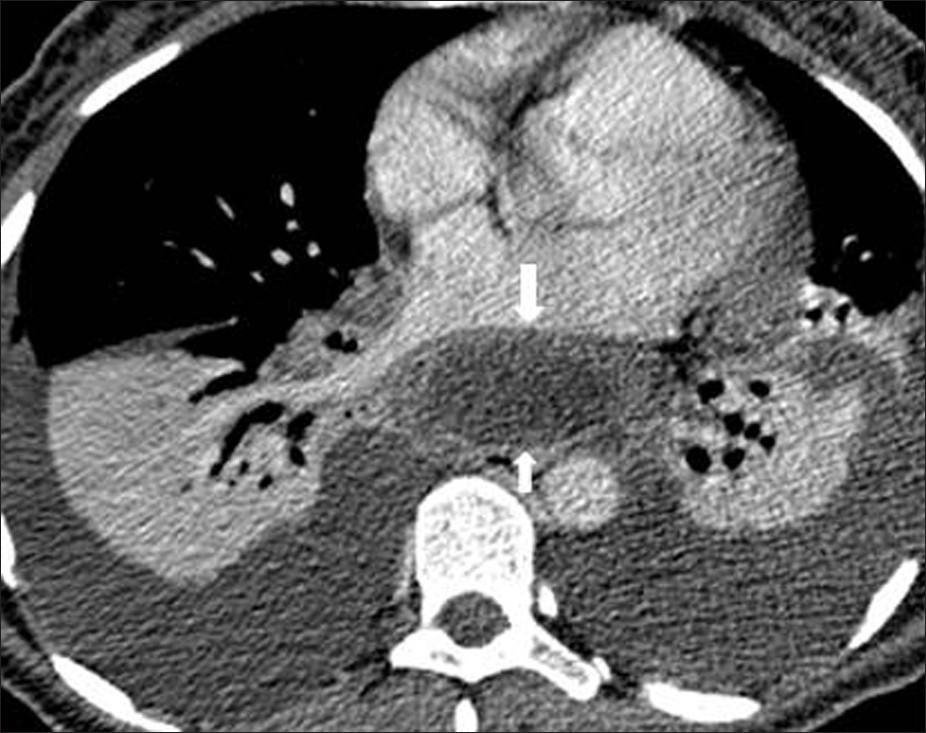

- Mediastinal unilocular hydatid cyst in a 28-year-old female with chest pain and dyspnea. (a) Contrast enhanced CT at the first admission (4 years prior to he current admission) shows a large low-attenuation mass (arrow) with smooth contour and round shape and thick wall in the mediastinum. Note also the displacement of the heart to the left.Four years later percutaneous aspiration under CT guidance, (b) Axial T1-weighted- (arrow) and (c-d) Axial and sagittal T2-weighted MR images show the hydatid localizations involving the mediastinum (arrow) and pleural space (thin arrow) .The signal intensity of the lesions is homogenous low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and of high signal intensity on T2- weighted images. MR images reveal that the cystic lesions were implanted both in the mediastinum and pleural space. (e) Photograph of the specimen.

- Mediastinal multilocular hydatid cyst in a 50-year-old female with severe chest pain. (a) Contrast enhanced CT shows multiple low-attenuation lesions (arrow) in the mediastinum. (b) T2-weighted MR image shows multilocular cystic lesions (arrows) with a thin wall and with high signal intensity contents. At surgery, mediastinal hydatid cysts were removed.

- Mediastinal calcified hydatid cyst in a 30-year-old man (a) Chest radiograph shows a well defined opacity in the right cardiophrenic angle (arrow). (b) Contrast enhanced CT shows a cystic lesion with segmental ring formed calcification that connects to the pericardium (arrow). At surgery calcified hydatid cyst was removed.

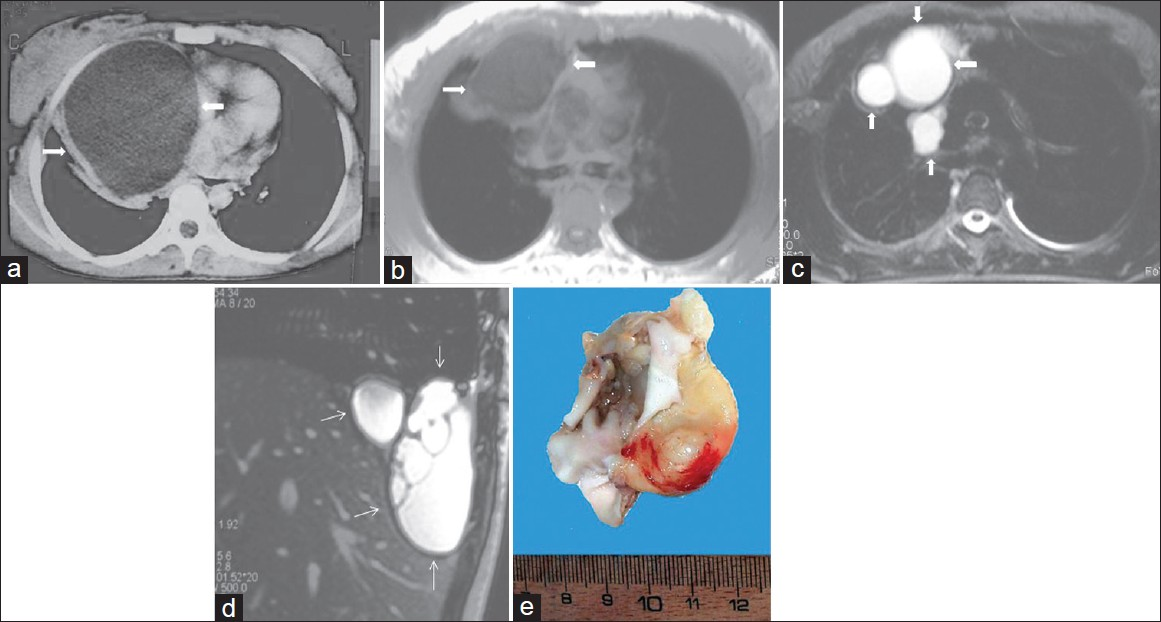

Cardiac hydatid cyst

Cardiac involvement by hydatid disease is rare and comprises 0.02 - 0.2% of all hydatid cases. The left ventricule is affected most often (50-60%), but the ventricular septum (10-20%), right ventricule (5-15%), pericardium (10-15%), and right or left atrium (5-8%) may be involved.[31] The appearance of HCs located in the heart and pericardium may vary from Type I to Type III.[31] CT allows reliable differentiation of cystic masses from solid tumors. However, CT is of limited value in the evaluation of pericardial and cardiac HCs due to motion artifacts. MRI appears to be the method of choice for specific diagnosis and exact assessment of hydatid cysts and their correlation with cardiac structures [Figure 17].[3134]

- Pericardial hydatid cyst in a 45-year old female with chest pain and arytmia. (a) Turbo FLASH sequence-proton density weighted axial image shows multiple hyperintense daughter cysts with low signal intensity capsule in the pericardium (arrows). (b) On turbo FLASH sequence-T2 weighted image, multiple daughter cysts demonstrate high - and homogenous signal intensity and low signal intensity rim and capsule (arrows). At surgery, hydatid cystic lesions were removed (reprinted with permission from 29).

MISCELLANEOUS

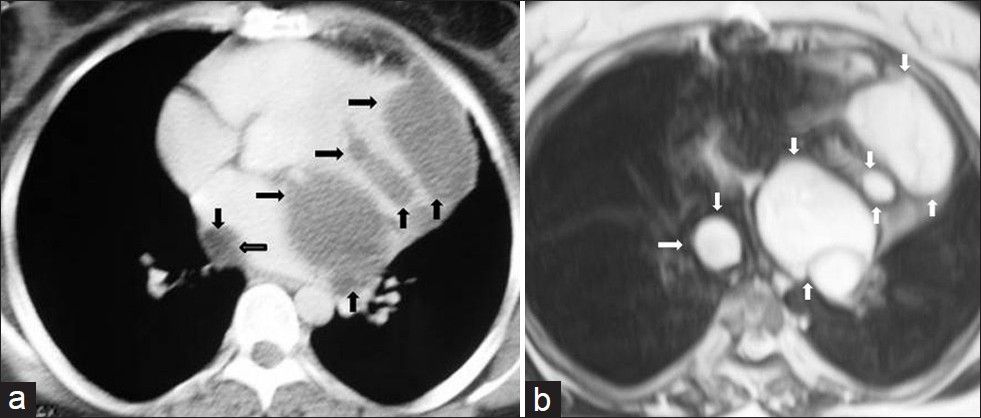

Hematoma

Mediastinal hematoma may occur as a sequela of anterior mediastinal vein rupture after trauma or coronary artery catheterization. Moreover, hematoma can occur within any mediastinal mass or after trauma.[835] Ninety percent of hematomas have areas of high attenuation during the early period. The attenuation of the mass will depend on the degree and age of the hemorrhage as well as on the beginning composition of the hematoma. Subacute or chronic hematomas of the mediastinum may appear as low-attenuation masses [Figure 18].[28]

- Chronic hematoma in a 40-year-old man with a chest trauma history. (a) Lateral chest radiograph shows a dense spherical mass in the anterior mediastinum (arrows) (b) Contrast enhanced CT shows a well-defined mass (arrows) with a calcified thick wall originating from the anterior mediastinum. (c) The signal intensity of the mass is of intermediate to moderate high signal intensity (arrows) on T1-weighted images,and (d) of heterogenous signal intensity on T2-weighted images (arrows). Diagnosis was confirmed at surgery.

On MRI hematomas show low signal intensity on T1 and T2-weighted images during the first 72 hr. When hematoma ages, the signal intensity on T1-weighted images increases and shows a more typical appearance.[2]

Thoracic duct cyst

A cyst of the thoracic duct is an uncommon disease rarely described in medical literature. Large cystic lesions may lead to the development of symptoms secondary to compression of the adjacent structures, including cough, chest pain, dysphagia, shortness of breath, and back pain.[36] On CT scan, a thoracic duct cyst appears as a single, smooth, round, or elliptic mass with an imperceptible wall and uniform attenuation. On T2-weighted MR imaging cyst have high signal intensity.[35] The differential diagnosis of thoracic duct cyst should include pericardial or pleural mesothelial cyst, thymic cyst, teratomatous cyst, bronchial or oesophagial cyst , neurenteric cysts and lymphangiomatous cysts.[36]

Cystic degeneration of solid tumors

Many tumors can undergo cystic degeneration and show both solid and cystic components in CT and MRI. True cystic lesions should be differentiated from the cystic degenerative changes observed in many solid tumors, lymph nodes, and from abscess and hematomas.[2] Goiters, thymomas, cystic teratomas, nerve root tumors, seminomas, and enlarged nodes from any organ tumor may show such a finding.[2]

Mediastinal lymphocele

A lymphocele is defined as a circumscribed collection of protein-rich lymphatic fluid without an epithelial lining. They can arise due to disruption of the normal lymphatic circulation by trauma, infection, or surgery. They are not commonly found in the mediastinum.[3738] Most lymphoceles, also known as chylous pseudocyst, cystic lymphangiomas, and lymphatic duct hygroma are usually solitary and well-circumscribed mass. On a chest radiograph, lymphocele appears as a smooth focal mediastinal mass or mediastinal widening. On CT, they usually appear as a well-defined, homogenous, low-attenuation mediastinal mass without evidence of contrast enhancement. The MRI signal intensity of a lymphocele may vary depending on the amount of proteinaceous fluid and lipid. Lymphocele containing a significant amount of proteinaceous fluid and lipid shows increased signal intensity on T1-weighted images. However, they show signal intensity similar to cerebrospinal fluid on all MR images.[3738]

Benign blood vascular tumors

Hemangioma

Vascular malformations can be classified as lymphatic, capillary, venous, arteriovenous, and mixed malformations depending on the basis of their histological make-up.[39] Moreover, these malformations can also be categorized as either low-flow lesions (capillary, cavernous, lymphatic, venous, and mixed malformations) or high-flow lesions (arteriovenous fistulas, AVMs) according to the contrast enhanced MR angiographic findings.[39] These classifications reflect the most frequent involvement of central nervous system and abdominal organs.[3940] However, mediastinal hemangiomas can also show clinical and radiological findings similar to vascular malformations in other organs. Mediastinal hemangiomas are rare tumors and most reports indicate that they account for 0.5% or fewer of all mediastinal tumors.[41–43] More than 90% of all mediastinal hemangiomas are capillary or cavernous.[4243]

Cavernous hemangioma

Most patients with cavernous hemangiomas are asymptomatic. Symtomatic patients present with cough, chest pain, or dyspnea due to compression or invasion of adjacent structures.[4144] These malformations usually occur in young patients. In chest radiograph and unenhanced CT, mediastinal hemangioma usually appear as a sharp, well-defined, or lobular mass in the anterior or posterior mediastinum.[41] However, these findings are not sufficient for a diagnosis.[41] In dynamic contrast-enhanced CT, hemangioma usually shows heterogenous attenuation. Following the contrast administration, hemangioma may show gradually increasing and persistent enhancement similar to hemangiomas elsewhere in the body.[4144] Cavernous hemangioma may appear as a multilocular cystic mass on both CT and MRI.[41] The presence of numerous punctate calcifications or phleboliths in the mass may suggest the diagnosis of hemangioma .[4344] On MRI, T1 and T2- weighted images reveal accurately the complex nature of the mass with areas of necrosis, blood-filled vascular spaces, and hemorrhage that exhibits high signal intensity.[41] Mediastinal cavernous hemangioma may show a vascular pattern, similar to cavernous hemangioma of the head and neck regions. In the head and neck reagions, cavernous hemangiomas are described as a low-flow or slow-flow vascular malformation. These are partially visible as a contrast enhanced lesion in the early phase (arterial phase) contrast enhanced MRA and are completely visible as a larger enhancing lesion in the late phase (venous phase) contrast enhanced MRA. These findings indicate that cavernous hemangioma has slow-blood flow pattern. In contrast to cavernous hemangioma, capillary hemangioma is seen as a large enhancing lesion, indicating that it has fast-blood flow in the early phase MRI. Thus, the contrast enhancement patterns on MRA reveal the hemodynamics of different types of hemangioma[2845]. Consequently, the CT and MRI findings of this rare entity can suggest the diagnosis of blood vascular tumor, but cannot differentiate a mediastinal cavernous hemangioma from other vascular or non-vascular pathologies. Thus, histological confirmation or surgery is required. Differential diagnosis of mediastinal cavernous hemangioma must include benign lesions such as, capillary hemangioma and venous hemangioma and malignant tumors such as hemangioendothelioma and hemangiopericytoma.[4144]

Lymphangiohemangioma

Lymphatic and venous malformations (LVM), also known as lymphangiohemangioma are considered as tumor-like vascular dysplasias that contain both vascular and lymphatic elements.[46] Lymphangiohemangiomas are most often found in the cervical and axillary regions but also localizations in the head and neck region have been described.[4647] They are rarely found in the mediastinum.[46] Multidetector CT angiography is considered to be the most useful imaging modality for pre-operative evaluation of vascular malformation. MDCT and MRI can show the vascular component of the mass and its relationship to normal vascular anatomy as well as the communicating vessels before surgery or interventional procedures.[4648] Mediastinal LVM is considered as a low-flow vascular malformation. Thus, MR signal intensity characteristics of LVM may vary depending on the proportions of lymphatic and venous components.[46] The venous components of the malformation will appear as collection of serpentine structures separated by septations. These serpentine structures represent slow-flowing blood in the venous channels and appear as high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images. Phleboliths can be present and appear as round, low-signal intensity lesions on MR imaging.[394749] Gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted images may show enhancement of the slow-flowing venous channels.[394950] Lymphatic components of the malformation may contain cystic structures of various sizes ranging from macrocystic to microcystic.The contents of uncomplicated cystic lesions typically are hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images, but following hemorrhage or infection fluid-fluid levels may be visible within these cystic lesions.[394050]

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, a number of mediastinal masses contain areas with CT attenuation values lower than those of chest wall musculature and higher than those of subcutaneous fat and therefore, these areas appear as cystic or cyst-like low-attenuation masses on CT. Compared with single detector helical CT, MDCT has greater accuracy for detecting mediastinal lesions. MDCT also allows more detailed evaluation of the entire thorax in a breath- hold without any loss of resolution and more consistent contrast enhancement with a single bolus of contrast. Thus, MDCT decreases the cost of examination. Moreover, it is rapid, more readily available, and inexpensive. MRI is an excellent tool for imaging mediastinal lesions, because of its intrinsic high soft tissue contrast resolution and direct multiplanar imaging. Coronal and sagittal MR images that may be obtained in conjunction with transaxial images provide the exact spatial relationship between tumor and other mediastinal structures. However, MRI also carries the same limitations as CT with inflammatory or inhomogeneous low-attenuation mediastinal lesions. Consequently, there may be some overlap in characteristics among various mediastinal masses and the correct diagnosis can only be made surgically.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2012/2/1/33/97750

REFERENCES

- Multisection CT: Scanning techniques and clinical applications. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1787-806.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thoracic application of multi- detector CT. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2007;49:29-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- MDCT in mediastinal imaging. In: Schoepf UJ, ed. Multidetector row CT of the thorax (1st ed). Berlin: Springer; 2004. p. :215-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bronchogenic cyst: Imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 2000;217:441-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Esophageal duplication cyst: CT and transesophageal needle aspiration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:531-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pediatric neuroimaging. (4th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. p. :743-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diverticulum of the pericardium: With observations on mode of development. Circulation. 1957;16:1040-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mulilocular thymic cyst: An acquired reactive process-study of 18 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:388-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic multilocular thymic cyst: CT features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:881-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- From the archives of the AFIP.Mediastinal germ cell tumors: Radiologic and pathologic correlation. Radio Graphics. 1992;12:1013-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mediastinal mature teratoma: Imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:985-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thoracic lymphangioma in adults: CT and MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:283-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mediastinal lymphangioma in adults: CT and MR imaging features. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1310-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign schwannomas: Pathologic basis for CT inhomogeneities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:141-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intrathoracic neurogenic tumors: MR-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:279-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Giant cystic thymoma with haemorrhage and necrosis: An unusual case. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2009;51:111-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiomatosis in the neck and mediastinum: An example of low-flow vascular malformations. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:981-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemomediastinum and bilateral hemothorax with extensive angiomatosis of anterior mediastinum. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2006;65:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mediastinal hydatid disease: Report of three cases. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1990;41:79-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intrathoracic extrapulmonary hydatid disease: Radiologic Manifestations. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2010;61:170-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- CT evaluation of the anterior madiastinum: Spectrum of disease. Radio Graphics. 1994;14:973-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vascular malformations and hemangiomas: A practical approach in a multidisciplinary clinic. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:597-608.

- [Google Scholar]

- Classification and imaging of vascular malformations in children. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2483-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mediastinal cavernous hemangioma in a child: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:985-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dynamic CT features of mediastinal hemangioma: More information for evaluation. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:276-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Head and neck haemangiomas: Contrast-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:140-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphatic and venous malformation or “lymphangiohemangioma” of the anterior mediastinum: Case report and literature review. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;59:575-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current managementof hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32:99-116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computed tomographic angiography: An important radiologic modality for assessing vascular malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1982-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging of symptomatic peripheral vascular malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:107-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological classification of soft-tissue vascular anomalies: MR correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:559-64.

- [Google Scholar]