Translate this page into:

Imaging Features of the Pleuropulmonary Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pearls and Pitfalls

Address for correspondence: Dr. Harbir Sidhu, Peninsula Radiology Academy, Plymouth International Business Park, Plymouth PL6 5WR, UK. E-mail: harbirsidhu@doctors.org.uk

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common disorder that affects the joints. RA is a systemic disease associated with relatively frequent and variable pleuropulmonary manifestations. This article reviews the common and potentially serious thoracic sequelae in terms of pleural disease, pulmonary nodules, airways disorders, and interstitial disease, as well as pulmonary side effects of antirheumatic medication. An imaging-guided approach to classification of RA-associated lung disease is outlined and the comparative values of different imaging modalities are discussed. An appreciation of current knowledge of epidemiology, pathological correlation, and prognostic implications of different RA-associated lung disease is provided. We highlight importance of considering pertinent differential diagnoses to avoid misdiagnosis, and outline common pitfalls in dealing with pleuropulmonary rheumatoid disease.

Keywords

Lung interstitial disease

pulmonary complications

rheumatoid arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common inflammatory joint disease (~1% prevalence). The disease is more common in women; however, thoracic manifestations (2-54%) occur more commonly in males (5 : 1). The first clinical report of pulmonary disease occurring in RA was published by Ellman and Ball in 1948.[1] Pleuropulmonary involvement occurs after the onset of joint disease in 85% of cases and in patients with high serum rheumatoid factor titers and eosinophilia. In a large autopsy study, Tyoshina et al reported that lung involvement was second to infection (18% vs 27%) as the most common cause of death.[2] This article outlines the imaging features of the pleuropulmonary manifestations of RA, highlighting useful diagnostic features and common pitfalls.

Pleural disease

Postmortem studies show pleuropulmonary manifestation in 40 to 75% of cases.[2] Pleural disease is associated with subcutaneous nodules, interstitial lung disease (ILD), and pericarditis, often in middle-aged men with high rheumatoid titers.[3]

Pleuritis (effusion +/- pleural thickening)

Effusions are seen in 3 to 5% of patients and usually occur during periods of active arthritis.[4] They are usually small, unilateral (L>R), and asymptomatic, with mild pain in 20 to 28% of patients.

They often resolve in a few weeks, but in some cases, may be persistent and recurrent. In various studies, almost all RA patients with pleural effusion were over 35 years, 80% were male, and approximately 80% had rheumatoid nodules.[4] A high prevalence of HLA-B8 and HLA-Dw3 genes is seen in patients with effusion.

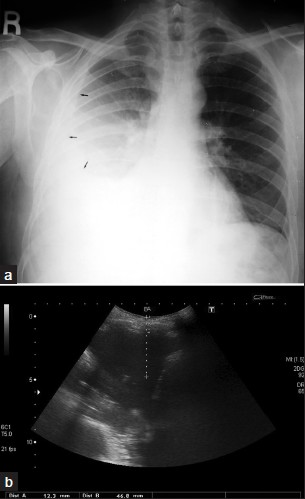

Chest radiography remains the initial examination of choice [Figure 1a]. Small effusions may be detected using lateral decubitus radiograph. Ultrasound [Figure 1b] is useful in the detection of pleural fluid and focal pleural thickening and in identification of the best site for pleural thoracocentesis and biopsy. CT imaging may detect a small amount of pleural fluid (sickle-shaped opacity), identify loculated collections (lenticular or rounded opacities), and diagnose underlying lung pathology and extrapleural diseases. MRI and/or nuclear medicine scans are not routinely used.

- A 52-year-old male with rheumatoid arthritis (RA): (a) PA chest radiograph shows a moderate right sided pleural effusion (arrow), (b) correlative imaging with ultrasound shows distances from skin to effusion.

Pyo/pneumothorax and bronchopleural fistula

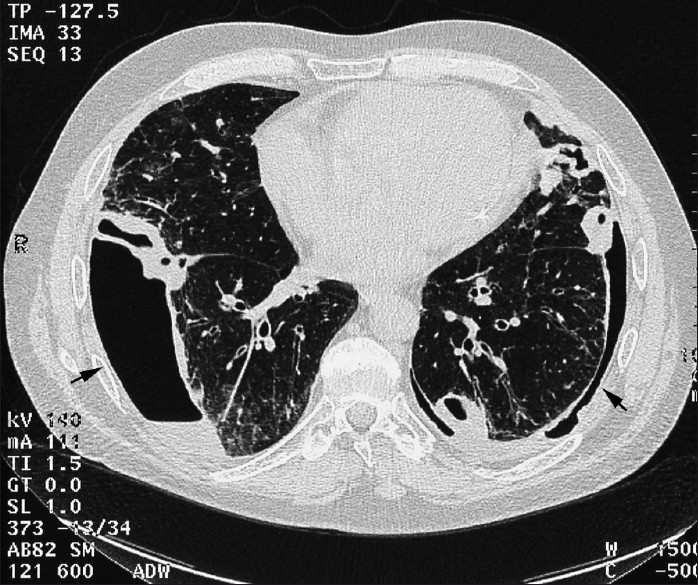

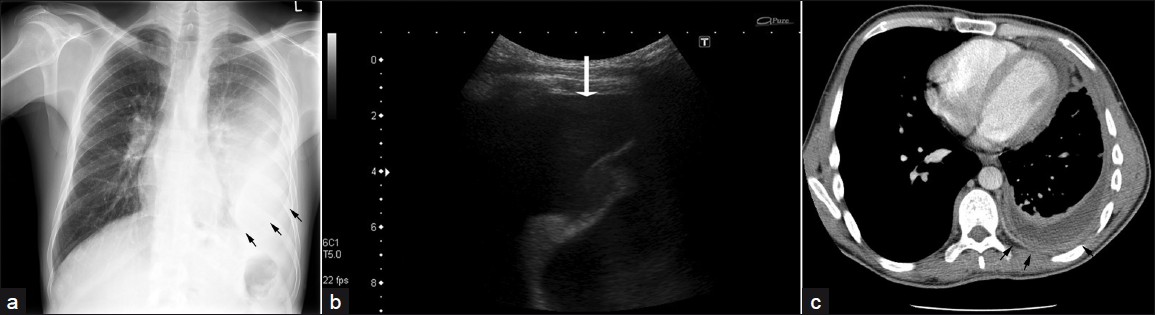

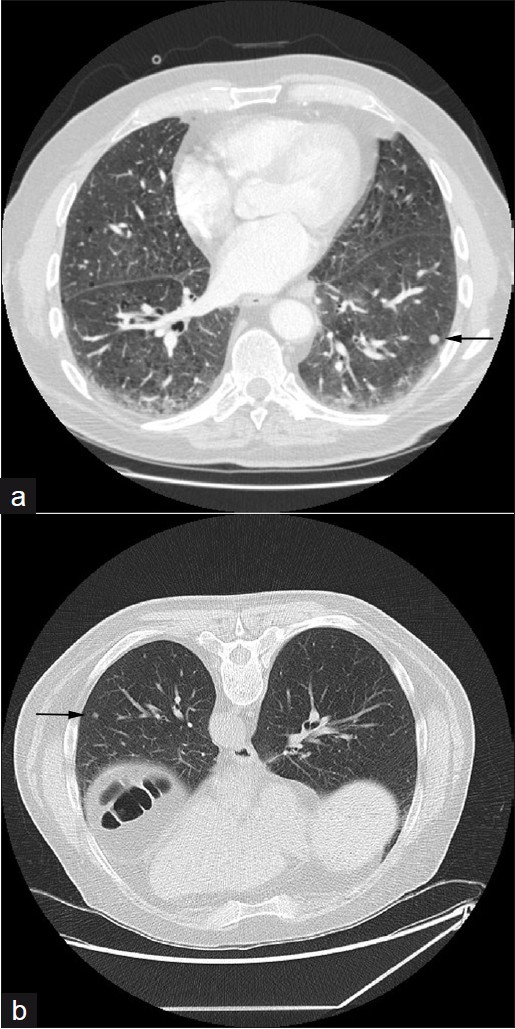

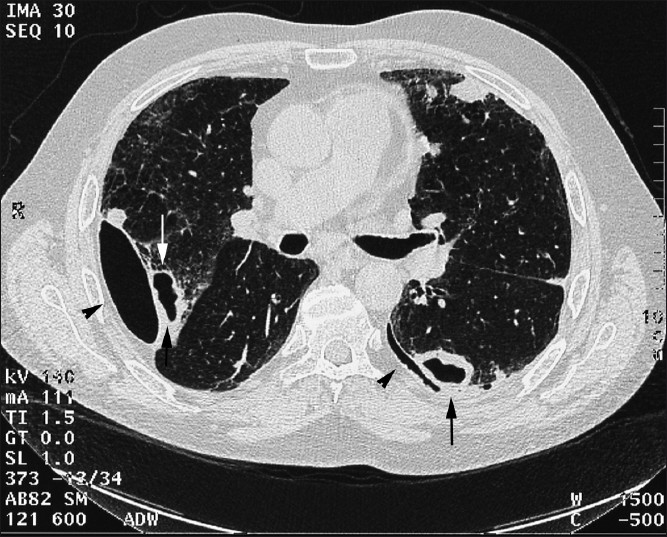

Pneumothorax [Figure 2] and empyema are unusual findings[3] in RA patients and may be secondary to cavitation of a necrobiotic nodule. A spontaneous sterile empyema may develop during active RA [Figure 3]. Empyema appears on CT as lenticular opacity that causes compression of the surrounding lung. The “split-pleural” sign and thickening of the pleural layer are typical for the organizing phase of infective empyema. Bronchopleural fistula represents an even more unusual thoracic manifestation of RA, though case reports have been documented.

- CT axial section from HRCT in a 68-year-old male RA patient shows subpleural basal nodules with pneumothoraces and effusions bilaterally.

- A 40-year-old male with RA: (a) PA chest radiograph shows a moderate left-sided pleural effusion (arrows), (b) US of same, (c) CT with high attenuation shows empyema, pleural thickening, and enhancement (arrows).

Pulmonary nodules

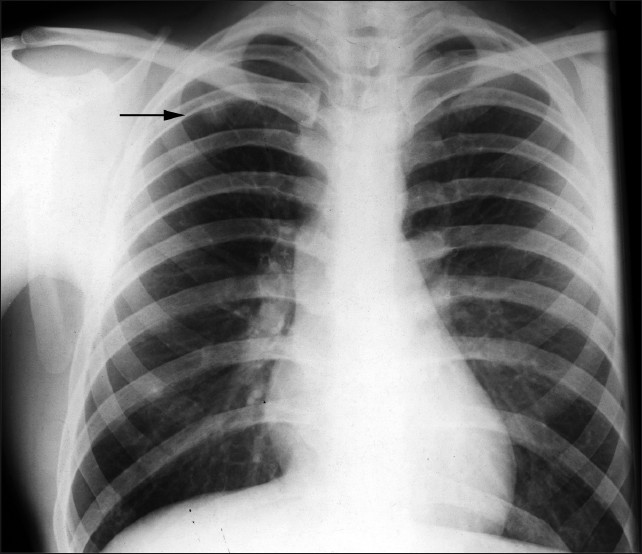

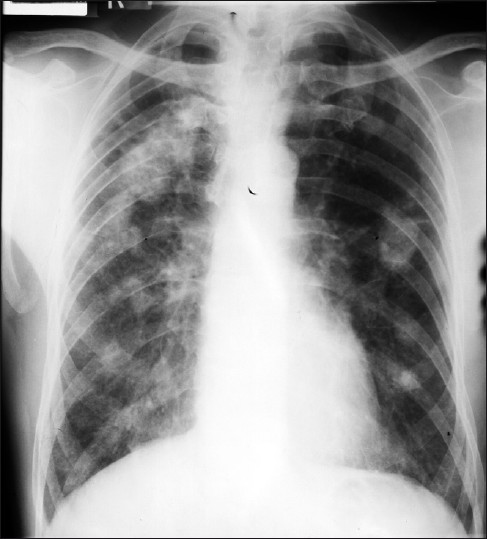

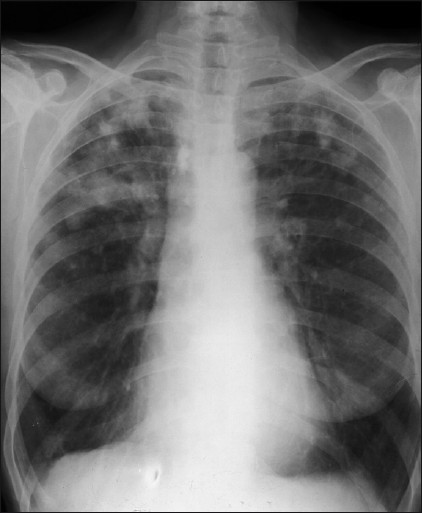

Rheumatoid nodules are more common in men, and usually occur in smokers with concomitant subcutaneous nodules and high titers of RF2. Nodules are well-circumscribed, located in lung, pleura, or pericardium and are histologically characterized by a central zone of eosinophilic fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by palisading fibroblasts. Nodules are identified in less than 1% of all chest radiographs [Figure 4] but have been identified in up to 33% of biopsy specimen series. They are frequently subpleural, usually multiple, and range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter [Figure 5]. Cavitation [Figures 6 and 7] is reported to occur in approximately 50% and calcification is rare.

- A 57-year-old male with RA shows a PA chest radiograph with a well-defined solitary nodule within the right upper zone.

- A 65-year-old male with RA: (a) arterial phase CT thorax axial section shows reticular subpleural opacification and necrobiotic nodules (arrow), (b) prone HRCT axial section taken three months later shows some resolution of the nodule (arrow) demonstrating their usual benign course.

- A 52-year-old female: frontal chest radiograph demonstrates two cavitating masses within the right lung (arrows).

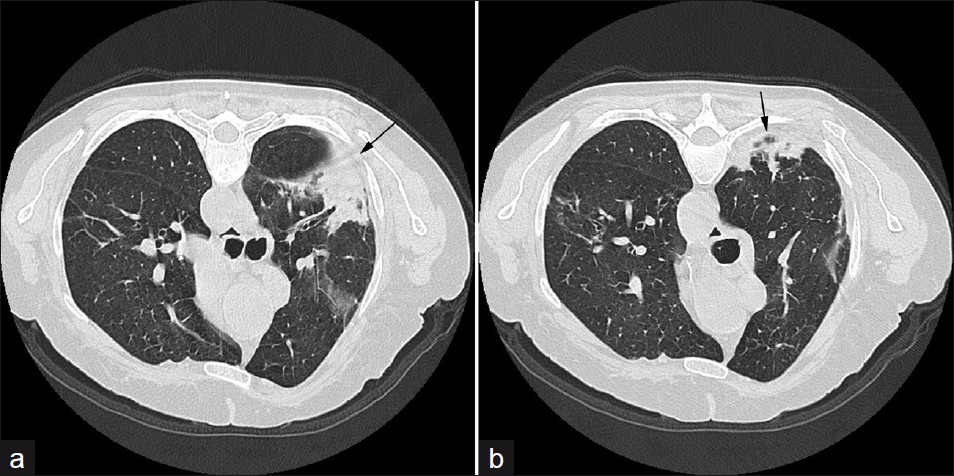

- HRCT axial sections in a 68-year-old male shows cavitating biopsyproven rheumatoid nodules with bilateral pneumothoraces (arrows) and effusions (arrowheads).

Radiologically, rheumatoid nodules are nonspecific and pertinent differential diagnoses include malignancy, infection, and vasculitides. Regression with time or during treatment (with steroids) may be helpful in the diagnosis (initial interval surveillance), as RA nodules usually run a benign course. They may demonstrate uptake on FDG-PET, but this is not useful in terms of distinguishing between rheumatoid nodules and malignant lesions.

Caplan's syndrome

Caplan described the association of RA with pulmonary nodules and pneumoconiosis in 1953.[5] Peripheral, well-defined nodules often appear quickly in crops of new subcutaneous nodules at times of increased RA activity [Figures 8 and 9]. Biopsy reveals inorganic dust within the necrotic nodule. These pulmonary nodules are usually asymptomatic and do not require treatment unless they rupture into the pleural space. This occurs in 2 to 6% of men affected by pneumoconioses.

- A 57-year-old male (ex-miner): A frontal chest radiograph shows Caplan's syndrome.

- A 70-year-old female: A frontal chest radiograph with features of Caplan's syndrome.

Airway and interstitial disease

In many studies, a strong association between RA and disease of the airways as identified on pulmonary function tests[3] has been well documented. Geddes et al demonstrated that patients with a normal chest x-ray had airflow obstruction.[6] Bronchiectasis (cylindrical type) has been demonstrated in several cases and may be isolated or secondary to interstitial disease (traction bronchiectasis). The commonest radiographic appearance is of basal linear markings and focal infiltrates. On CT, bronchiectasis and brochiolectasis have been demonstrated in 30% of unselected patients.[3] On high-resolution CT (HRCT), a “tree-in-bud” appearance may reflect disease of the small airways.

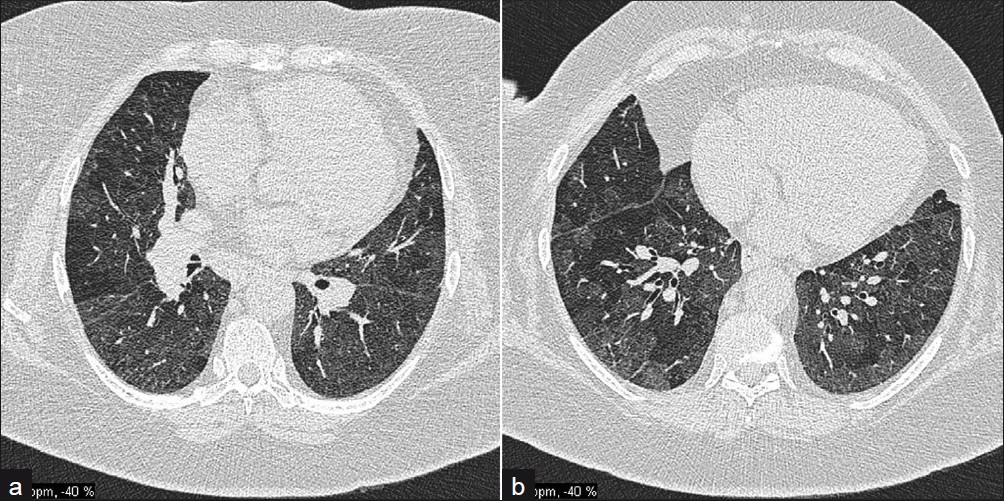

Obliterative bronchiolitis [Figure 10] is rare, tending to occur in women with well-established RA. Patients present with a dry cough and rapidly progressive dyspnea. This manifestation carries a poor prognosis. Chest radiographs may be normal. HRCT demonstrates a geometric, mosaic attenuation pattern. Expiratory scans confirm air trapping. Bronchocentric granulomatosis is even rarer.

- A 57-year-old male with obliterative bronchiolitis secondary to RA; (a) and (b) HRCT axial sections demonstrate marked mosaic pattern attenuation.

Cricoarytenoid arthritis has been reported in 20 to 66% of RA patients.[7] On CT, between 54 and 72% (fewer in symptomatic) cases are identified. It is more common in female patients and CT may show cricoarytenoid erosion, luxation, and abnormal position of the true vocal cords.

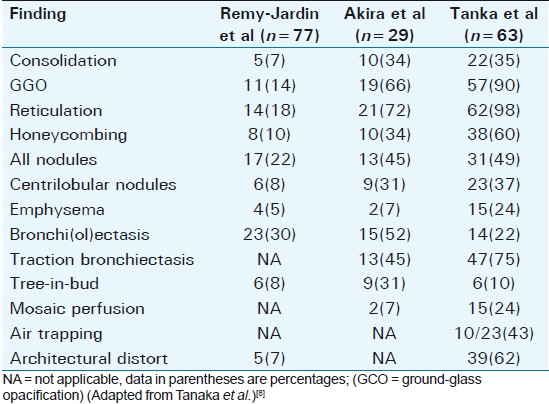

ILD is associated with RA, radiographic abnormalities occur in 1 to 6%, and histological changes in 80%. The appearances on chest radiograph are of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis). HRCT demonstrates ILD patterns. Diffuse interstitial pulmonary amyloidosis may mimic RA and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Tanaka et al (2004) evaluated CT finding in RA and categorized findings according to pathologic features and compared their results with previous studies (summarized in Table 1).[8]

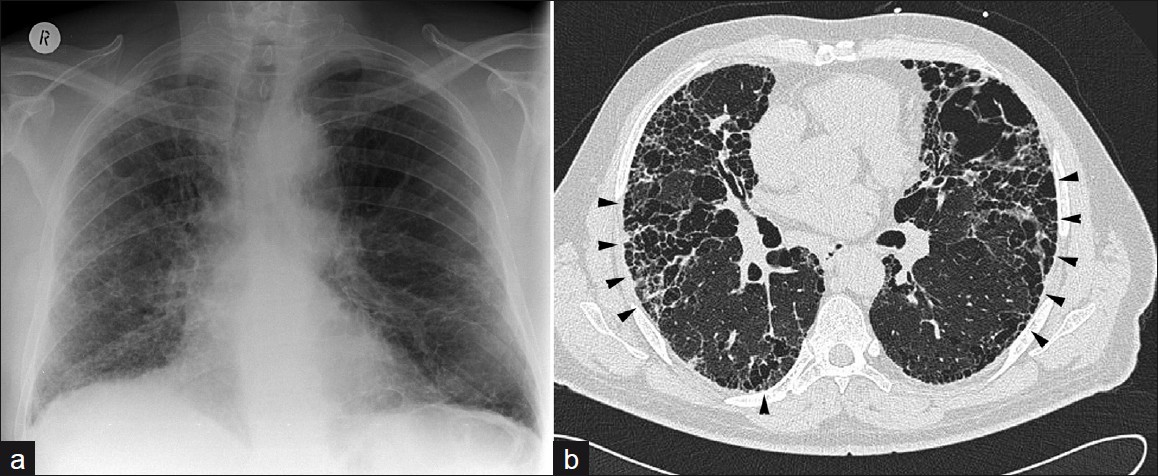

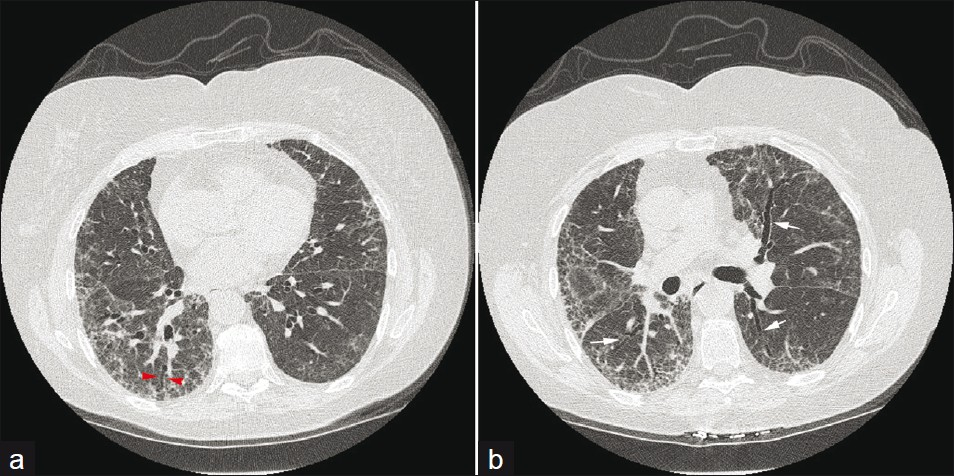

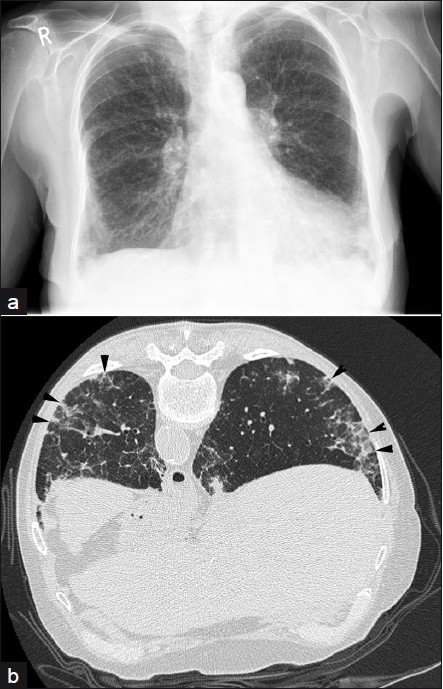

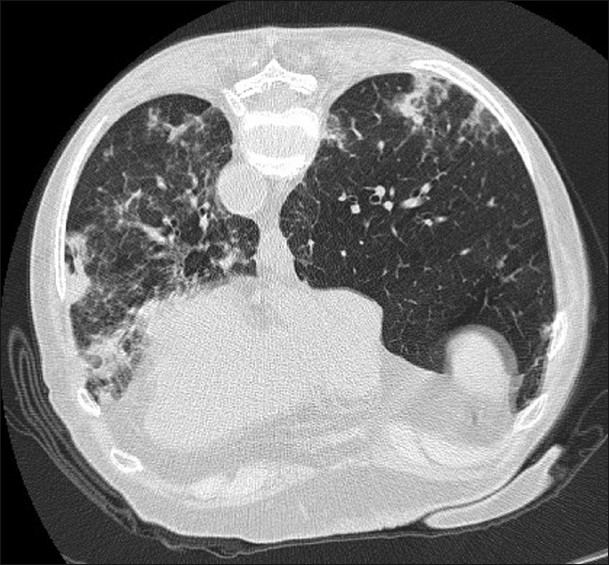

Subsequent to the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society consensus classification, RA may be seen to be associated with three main types of CT patterns: Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) [Figure 11], non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) [Figure 12], and organizing pneumonia [Figure 13]. UIP and NSIP have significant overlap, demonstrating ground-glass opacification and reticulation, and honeycombing has been seen in more than half of NSIP cases in recent studies.[8]

- A 63-year-old male: (a) Chest X-ray shows bibasal fibrosis, (b) prone HRCT demonstrates UIP with marked honeycombing (arrowheads) and features of UIP.

- A 65-year-old male: (a and b) axial HRCT sections show NSIP with subpleural ground-glass opacification and traction bronchiectasis (arrows).

- A 74-year-old male: (a and b) axial HRCT show an organizing pneumonia (arrows) in the left lung, attributable to RA.

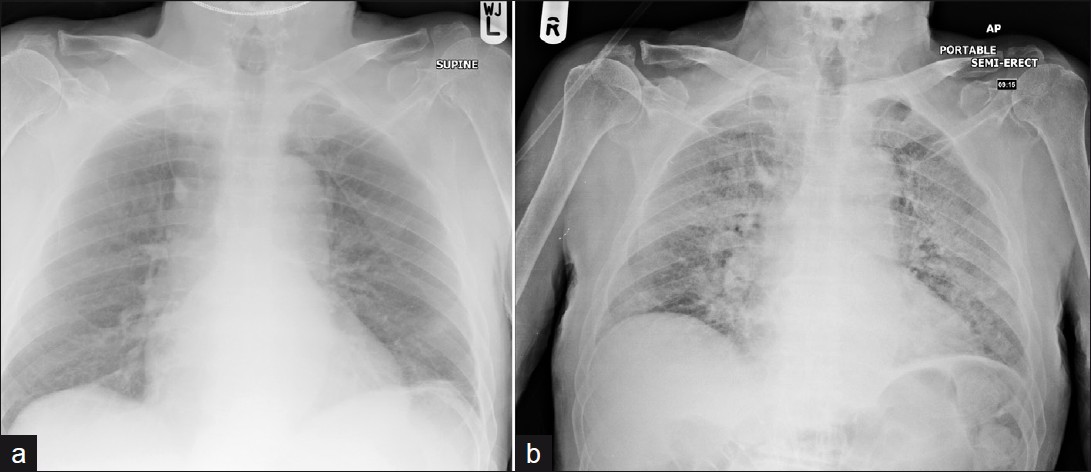

Drug-induced lung disease

Drug-induced lung disease from disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, with no pathognomonic features, is difficult to diagnose. Methotrexate may cause acute interstitial pneumonitis in 1 to 5% of patients, and can be an unpredictable and life-threatening side effect of therapy.[9] Presentation is often subacute, with progressive cough, dyspnea, and fever. In a small number of patients, there may be rapid progression to respiratory failure. CXR demonstrates diffuse, bilateral, usually basal interstitial or alveolar infiltrates.[3] Lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions may suggest the diagnosis; HRCT shows an NSIP pattern [Figure 14]. Methotrexate can also give rise to diffuse alveolar damage [Figure 15] and various other pleuropulmonary disorders.

- A 73-year-old female with methotrexate-induced lung disease: (a) frontal chest radiograph demonstrates basal reticular shadowing and (b) prone HRCT shows septal thickening, nodularity, and basal fibrosis (arrowheads); consistent with NSIP. Improvement was seen following cessation of the drug.

- A 68-year-old male who developed marked diffuse alveolar damage as seen on frontal chest radiograph (a) prior to therapy and (b) after 8 weeks of methotrexate therapy.

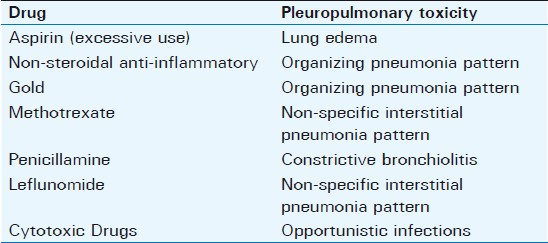

The numerous drugs/agents used to treat RA can give rise to a host of lung disease [Figure 16]; the typical patterns are given in Table 2.

- A 64-year-old female who developed an organizing pneumonia pattern of lung disease following gold therapy shown on HRCT.

CONCLUSIONS

Respiratory manifestations of RA encompass a multitude of radiological features and awareness of the entire spectrum is crucial. The term “rheumatoid lung” is an increasingly obsolete term that does not allow the clinician to appreciate the variety of presentations. In a minority of patients, pleuropulmonary manifestations may be the presenting feature of the disease.

A history of RA is important when considering the differential diagnosis of thoracic pathology. However, patients with RA are equally, if not more, susceptible to non-rheumatoid pathology, e.g., infection or primary bronchial carcinoma. The therapeutic agents employed in RA management can also result in a host of concomitant lung pathologies. It is often a diagnostic conundrum to differentiate between primary interstitial rheumatoid disease and drug-induced changes. A high index of suspicion and adequate temporal correlation with treatment is vital. It is important to employ the most appropriate imaging modalities; this is usually achieved through first-line use of chest radiography combined with HRCT to fully characterize lung pathology. The roles of MRI and nuclear medicine are poorly defined and limited at present.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2011/1/1/32/82244

REFERENCES

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Classical rheumatoid lung disease. Balliere's Clin Rheum. 1993;7:1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of the pulmonary manifestations of systemic disease. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:621-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Certain unusual radiological appearances in the chest of coal miners suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. Thorax. 1953;8:29-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cricoarytenoid RA: An important consideration in aggressive lesions of the larynx. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:970-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from: http://www.pneumotox.com/