Human Herpes Virus-8-Associated Multicentric Castleman's Disease in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Patient with a Previous History of Kaposi's Sarcoma

Address for correspondence: Dr. Guan Huang, Department of Radiology and Diagnostic Imaging, University of Alberta Hospital, 2A2.41 WMC, 8440-112 Street, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2B7, Canada. E-mail: guanhuang@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Human herpes virus-8 (HHV-8)–associated Castleman's disease (CD) is a rare non-cancerous B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients. We report a case of HHV-8–associated CD in an HIV-positive patient with a previous history of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). The patient presented with progressive splenomegaly and diffuse lymphadenopathy, which can be seen in multicentric CD, KS, and HIV-associated lymphoma. There are no reliable clinical or imaging features to differentiate these diseases. Lymph node biopsy confirmed HHV-8–associated CD and excluded KS and lymphoma. Due to differences in treatment options and prognosis between the three etiologies, it is important for radiologists to include HHV-8–associated CD in the differential diagnosis when encountering HIV-positive patients that present with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Keywords

Human immunodeficiency virus

Kaposi's sarcoma

multicentric Castleman's disease

INTRODUCTION

Castleman's disease (CD), also known as angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia or giant lymph node hyperplasia, is a rare non-cancerous B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by marked lymphadenopathy.[1] The more traditional morphologic classification divides CD into unicentric disease where a single nodal group is involved and multicentric disease where there is diffuse lymphadenopathy.[2] With advancements in the understanding of the disease entity, CD is now classified into the following histopathologic subtypes: Hyaline-vascular, plasma cell, human herpes virus-8 (HHV-8)–associated CD, and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) not otherwise specified.[2] Hyaline-vascular CD usually presents unicentrically and lacks the systemic symptoms associated with other CD subtypes.[3] As it is localized to a single region, surgical resection is often curative. Plasma cell CD is commonly multicentric and is often associated with POEMS syndrome (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes).[3] HHV-8–associated CD, a plasmablastic variant of CD, generally occurs in immunocompromised patients, especially human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals.[3] Virtually all cases of MCD in HIV-positive patients are associated with HHV-8.[2] MCD not otherwise specified is often a retrospective diagnosis and patients are typically HHV-8 negative.[3] HHV-8–associated CD shares overlapping clinical and imaging features with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS) and HIV-associated lymphomas, and only tissue biopsy provides definitive diagnosis. As the treatment options and prognosis of these diseases vary, it is important for radiologists to consider HHV-8–associated CD when assessing HIV-positive patients with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

CASE REPORT

A 49-year-old Caucasian male presented to hospital in 2015 with a 5-day history of fever, generalized malaise, left upper quadrant pain, and hypoxia. His past medical history was significant for HIV infection which was well controlled with antiretroviral therapy (ART) involving raltegravir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine. His CD4 count at presentation was 250 cells/μl. Initial laboratory work-up revealed hemoglobin 110 g/l, platelets 35 (109/l), albumin 32 g/l, and C-reactive protein (CRP) 242.5 mg/l. A computed tomography (CT) examination in 2011 had shown diffuse intrathoracic and intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, and a diagnosis of KS was obtained from an inguinal lymph node biopsy. The patient was treated with multiple cycles of doxorubicin and paclitaxel leading to KS remission, while the lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly remained stable on follow-up CT examinations.

A chest and abdominal CT performed on the current admission revealed interval enlargement of the lymphadenopathy throughout the body compared to a CT performed 3 months before [Figures 1 and 2]. An aortopulmonary window mediastinal lymph node, as an example, enlarged from 1.3 cm in maximum short-axis diameter to 1.9 cm. The spleen also further enlarged from 13.8 × 6.7 × 15.2 cm to 14.3 × 8.8 × 15.3 cm [Figure 3]. The differential diagnosis included KS progression, MCD, or lymphoma. An excisional biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node confirmed HHV-8–positive CD. Histopathologic analysis ruled out KS and lymphoma.

- 49-year-old HIV-positive man presented with fever, malaise, and respiratory symptoms, subsequently diagnosed with HHV-8–associated CD. Axial and coronal contrast-enhanced CT images of the upper thorax (a and b) during current admission and (c and d) 3 months earlier demonstrate interval enlargement of multiple mediastinal and axillary lymph nodes. An AP window lymph node and a left axillary lymph node (arrows) measure 1.9 cm and 1.5 cm in maximum short-axis diameters, respectively, in the current study, compared with 1.3 cm and 1.1 cm previously.

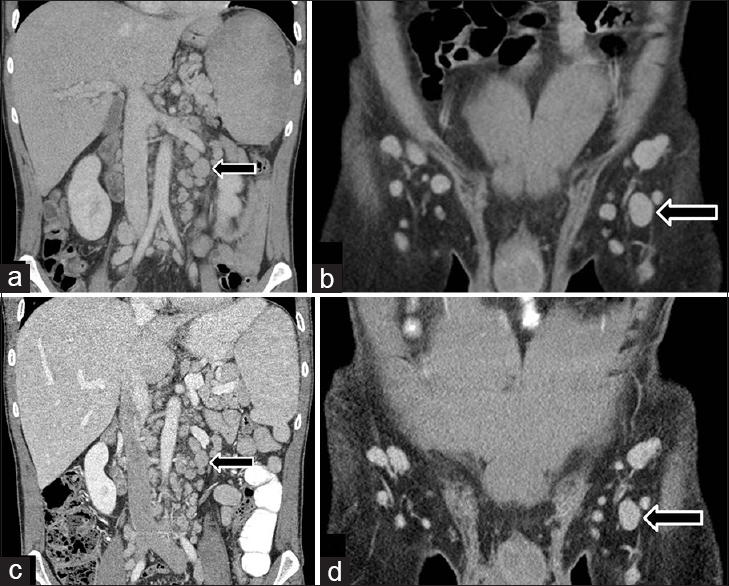

- 49-year-old HIV-positive man presented with fever, malaise, and respiratory symptoms, subsequently diagnosed with HHV-8–associated CD. Coronal contrast-enhanced CTs of the abdomen during (a and b) current admission and (c and d) 3 months earlier demonstrate interval enlargement of multiple retroperitoneal and inguinal lymph nodes. A left para-aortic lymph node and a left inguinal lymph node (arrows) measure 1.8 cm and 1.5 cm in maximum short-axis diameters, respectively, in the current study, compared with 1.3 cm and 1.2 cm previously.

- 49-year-old HIV-positive man presented with fever, malaise, and respiratory symptoms, subsequently diagnosed with HHV-8–associated CD. Axial contrast-enhanced CTs of the upper abdomen during (a) current admission and (b) 3 months earlier demonstrate interval enlargement of the spleen (arrows).

The patient was started on treatment for HHV-8–associated CD with rituximab and ganciclovir. The patient noted a marked improvement in symptoms by the time of the follow-up clinic appointment 3 months after initiation of treatment. Biochemical markers were also improved with hemoglobin 146 g/l, platelets 235 (109/l), and albumin 45 g/l (CRP level was not tested at follow-up).

DISCUSSION

HHV-8–associated CD most often occurs in immunocompromised patients, especially HIV-positive patients.[4] It manifests with fluctuating fever, generalized malaise, respiratory symptoms, hypoalbuminemia, high interleukin-6 (IL-6) and CRP levels, and hepatosplenomegaly.[4] The severity of symptoms correlates with the HHV-8 viral load suggesting that active viral replication plays an important role in disease pathogenesis.[4] On CT, HHV-8–associated CD is characterized by diffuse lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, pericardial and pleural effusions, and ascites.[3] On contrast-enhanced CT, the involved nodes in HHV-8–associated CD enhance homogeneously, although the degree of enhancement is not as marked as in hyaline-vascular CD.[3] The incidence of HHV-8–associated CD has no correlation with CD4 count or ART use.[5]

KS is a multifocal angioproliferative disorder of vascular endothelium.[6] It primarily affects mucocutaneous tissues, but may involve the viscera and can cause diffuse lymphadenopathy.[6] As HHV-8 is the causative agent in both KS and HHV-8–associated CD, it is not surprising that KS may occur concomitantly in up to 75% of patients with MCD.[4] Lymphadenopathy secondary to KS often demonstrates hyper-enhancement on post-contrast CT.[7] This feature may potentially allow for differentiation from HHV-8–associated CD and lymphoma, as the lymphadenopathy in the latter diseases is usually not hypervascular on post-contrast CT.[3]

Another commonly encountered entity in HIV-positive patients is lymphoma. This most commonly occurs when the CD4 count is below 350 cells/μl.[8] HHV-8–associated CD may mimic lymphoma clinically and on imaging. Both lymphoma and HHV-8–associated CD may present as diffuse, mildly enhancing lymphadenopathy. HHV-8–associated CD may itself progress to a particular form of large B-cell lymphoma termed HHV-8–positive plasmablastic lymphoma.[2] Currently there is no reliable imaging method to differentiate between HHV-8–associated CD and lymphoma. However, the application of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) for biopsy-proven HHV-8–associated CD has been studied.[9] A preliminary study of nine patients by Barker et al., suggested that FDG PET/CT is more sensitive than CT in detecting active multicentric CD and that this imaging modality may have a role in selecting biopsy sites and in staging and disease monitoring.[9]

Despite the challenges in differentiating between HHV-8–associated CD, KS, and HIV-associated lymphoma, there is great clinical importance in doing so because of the differing treatments and prognoses of these diseases. Common therapeutic approaches for HHV-8–associated CD include systemic chemotherapy and antiviral and antiproliferative regimens, especially anti-CD20 antibody therapy (e.g. rituximab).[5] Prognosis of HHV-8–associated CD was traditionally poor with a median survival in the order of months, although in recent years, the outlook has improved dramatically with the introduction of rituximab-based therapy.[5] Treatments commonly used in KS include single-agent liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin and daunorubicin) and single-agent paclitaxel.[6] The prognosis for KS has significantly improved in the post-ART era leading to KS regression in many cases.[6] HIV-associated lymphoma can be treated with chemotherapy and/or autologous stem cell transplantation.[10] The prognosis in patients with HIV-associated lymphoma now approaches that observed in the general population.[10]

CONCLUSION

HHV-8–associated CD is a relatively rare disease in HIV-positive patients. It often presents with fluctuating fever, malaise, and respiratory symptoms, and laboratory findings including hypoalbuminemia, elevated IL-6 and CRP levels. It can mimic KS and lymphoma on imaging, while co-existing HHV-8–associated CD with KS and/or lymphoma is also recognized. Definitive diagnosis requires tissue biopsy. Due to differences in treatment options and prognosis between the etiologies, it is important for radiologists to include HHV-8–associated CD in the differential diagnosis when encountering HIV-positive patients who present with diffuse lymphadenopathy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2015/5/1/59/168713

REFERENCES

- Multicentric castleman's disease in HIV infection: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS Rev. 2008;10:25-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Castleman disease: An update on classification and the spectrum of associated lesions. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:236-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features and outcome in HIV-Associated Multicentric Castleman's Disease. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2481-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines on the Treatment of Skin and Oral HIV-Associated Conditions in Children and Adults. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. p. :2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related lymphoma since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Blood. 2000;96:2730-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- FDG-PET/CT imaging in the management of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:648-52.

- [Google Scholar]