Translate this page into:

Concurrent, Bilateral Presentation of Immature and Mature Ovarian Teratomas with Refractory Hyponatremia: A Case Report

*Corresponding author: Kanupriya Vijay, MD, Radiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas – 75390, TX, United States. Kanupriya.vijay@utsouthwestern.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Tejani AS, He L, Zheng W, Vijay K. Concurrent, Bilateral Presentation of Immature and Mature Ovarian Teratomas with Refractory Hyponatremia: A Case Report. J Clin Imaging Sci 2020;10:23.

Abstract

We present the imaging and histopathological findings in a 32-year-old female who presented to the erectile dysfunction with progressively worsening abdominal pain over the past 2 months. Computed tomography abdomen and pelvis revealed bilateral ovarian teratomas, left significantly larger than right. There was associated fat stranding, mesenteric/omental stranding, and ascites worrisome for rupture versus peritoneal carcinomatosis. Histopathology confirmed a left immature teratoma (Grade 2), right mature teratoma, and peritoneal gliomatosis from possible tumor rupture before surgery.

Keywords

Teratoma

Ovarian

Neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Teratomas are the most common germ cell tumor of the ovary, accounting for 20–27% of ovarian tumors.[1,2] Teratomas are further categorized into mature (solid or cystic) teratomas, immature teratomas, and monodermal (highly specialized) teratomas.[3] Mature cystic teratomas, the most common and often benign subcategory, usually present unilaterally; however, mature cystic teratomas may occur bilaterally in 8–15% of cases.[4,5] Immature teratomas represent a more rare and aggressive subcategory primarily affecting a younger age group, comprising 1–3% of teratomas, and occurring bilaterally in only 10% of those cases.[6,7] The following case report details the presentation of concurrent mature and immature teratomas complicated by likely paraneoplastic, SIADH-like syndrome.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 32-year-old woman, gravida 2 para 2, presented to our institution with a history of progressively worsening abdominal pain over the past 2 months. She reported intermittent, suprapubic, and central abdominal pain with associated nausea, weight gain, abdominal distension, early satiety, constipation, and urinary frequency. Similar episodes of pain were diagnosed as Helicobacter pylori induced gastritis and treated unsuccessfully with proton-pump inhibitors. Tumor markers revealed elevated CA 125 (244.9) and CA 19-9 (76).

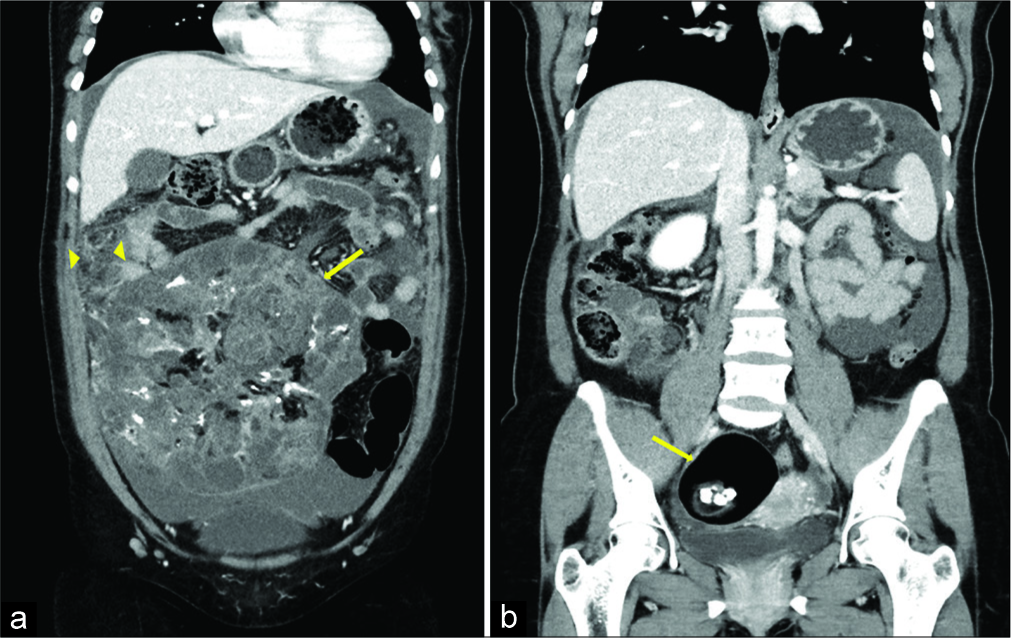

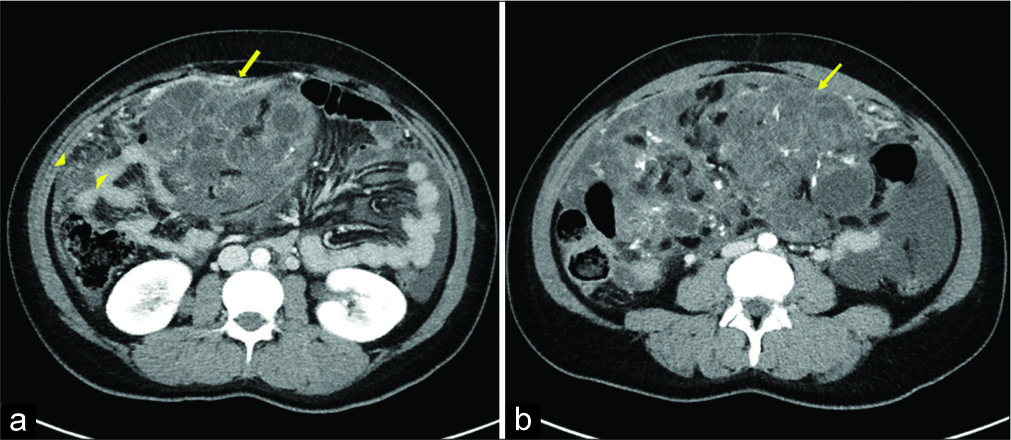

A computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis were performed per discretion of the ordering emergency room physician, which revealed a large heterogeneous mass in the left adnexa measuring 19 × 17 × 10.4 cm, containing fat, calcification, and soft-tissue consistent with a teratoma [Figures 1a-1b, 2a-b]. However, there was a significant mass effect, mesenteric/omental stranding, and ascites concerning for malignant transformation and peritoneal carcinomatosis versus intraperitoneal rupture with resultant granulomatous peritonitis [Figures 1a and 2a]. Further findings included a mature ovarian teratoma measuring 5.4 × 5.4 × 6.9 cm in the right adnexa [Figure 2b].

- A 32-year-old woman presenting with progressively worsening abdominal pain subsequently diagnosed with bilateral teratomas (immature and mature). Coronal reformats of contrast- enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis (a) demonstrates a large, heterogeneous soft-tissue mass (arrow) with a small amount of fat and calcifications. Omental fat stranding (arrowheads) is seen along the right superolateral aspect of mass along with small volume ascites (a). Additional coronal image (b) demonstrates a well- circumscribed mass in the right adnexa (arrow) with intralesional fat and calcifications.

- A 32-year-old woman presenting with progressively worsening abdominal pain subsequently diagnosed with bilateral teratomas (immature and mature). Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (a) demonstrates a large heterogeneous soft-tissue pelvic mass (arrow) with internal fat with surrounding omental fat stranding (arrowhead). Additional axial image (b) demonstrates a large heterogeneous soft-tissue pelvic mass with small amount of fat and calcification, consistent with immature teratoma.

Although surgery was indicated, initial evaluation in the emergency department demonstrated severe hyponatremia (serum sodium of 116 mmol/L), and our patient was admitted for management in the MICU. Initially, her hyponatremia responded to fluid resuscitation (serum sodium 125 mmol/L) and she was transferred to the gynecology team for further work-up; however, she required readmission to the MICU for refractory hyponatremia (serum sodium 118 mmol/L). Her serum sodium corrected after management with fluid restriction and salt tablets, and she was transferred to gynecology for planned surgery. Pre-operative laboratories demonstrated serum sodium 130 mmol/L, plasma osmolality 240 mmol/L, urinary sodium 220 mWq/L, and urine osmolality 779 mEq/L. Other preoperative laboratories indicated normal adrenal and thyroid function.

Intraoperative findings confirmed bilateral ovarian masses and ascites; however, gross peritoneal carcinomatosis was not reported. Samples were then sent for surgical pathology following bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, and pelvic lymph node dissections. Our patient’s sodium levels immediately increased to normal after surgery and continued to normalize as she was weaned off of fluids and salt tablets.

Macroscopic examination of the bilateral salpingo- oophorectomy specimen revealed a 21.5 × 17.5 × 8.5 cm focally disrupted, enlarged left ovary and an 8.0 × 6.0 × 5.5 cm cystic right ovary. The outer surface of the left ovary was remarkable for numerous adhesions with a 12.0 × 6.0 × 0.5 cm portion of omentum attached. Serial sectioning revealed numerous tan- white and tan-yellow solid and cystic areas admixed with hair, skin, and cartilaginous tissues. The outer surface of the right ovary was remarkable for a scant amount of adhesions. It was filled with yellow mucoid material including skin, cartilage, and teeth attached to the inner lining of the ovarian wall.

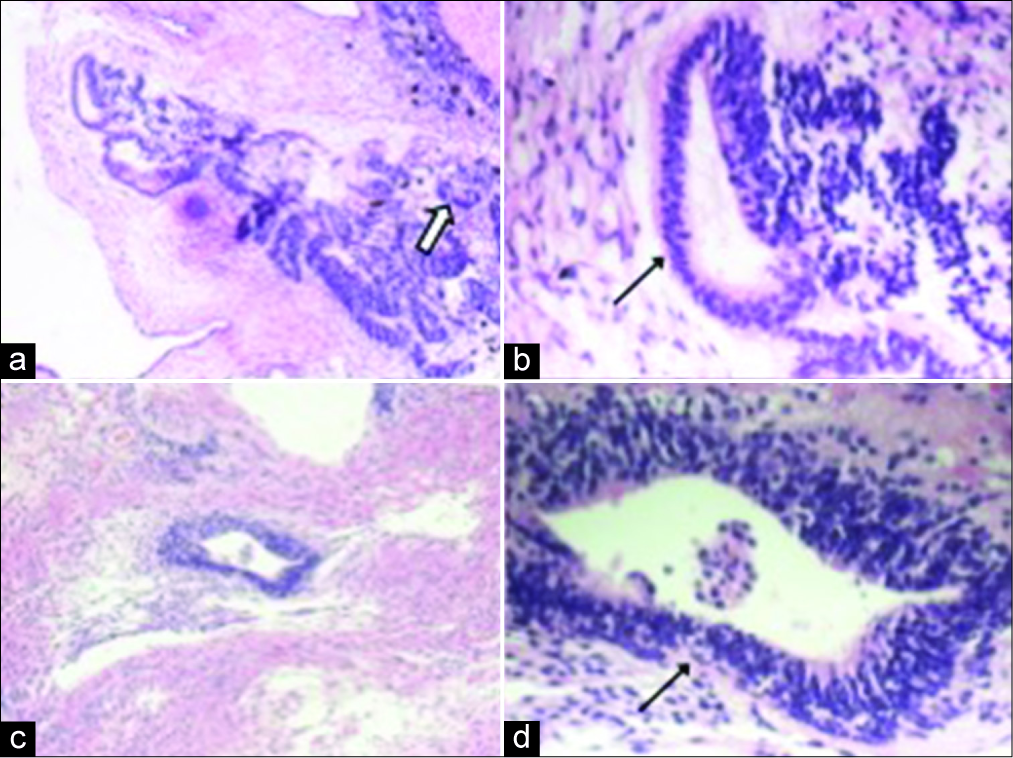

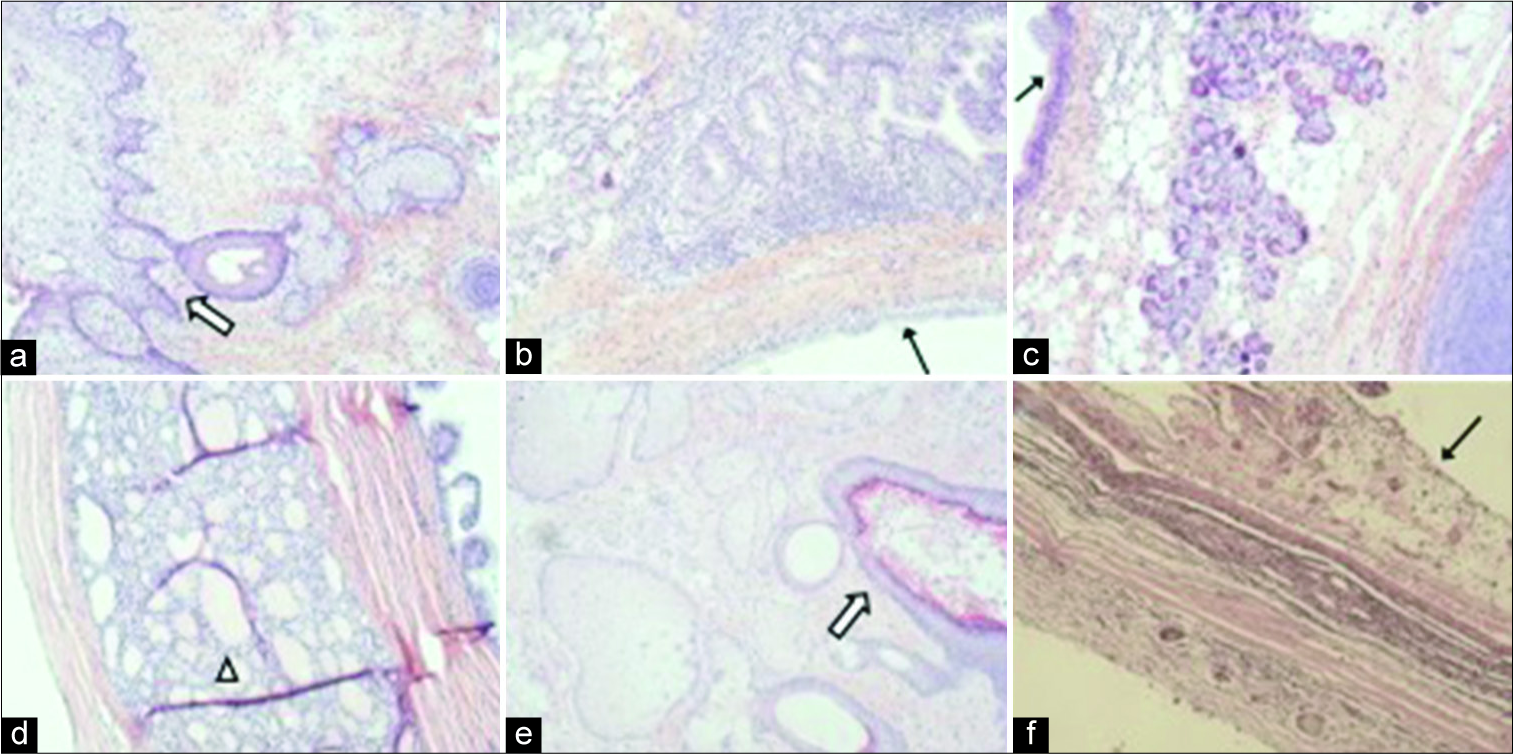

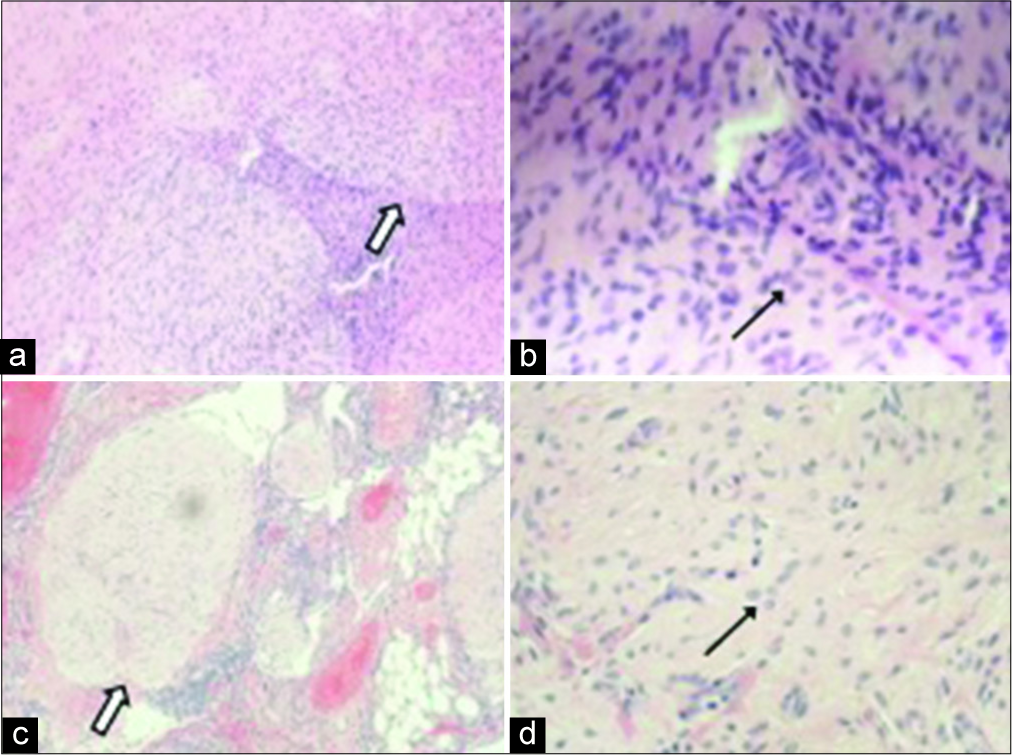

Microscopically, the left ovary revealed a solid tumor with areas of neurotubules and neuroepithelial rosettes [Figure 3a-d] along with mature components including skin appendages, cartilages, and pancreatic and neural glial tissues [Figure 4a-c]. The diagnosis of immature teratoma (Grade 2) was made based on the presence of neurotubules in two low-power fields as described previously.[8] The right ovary, on the other hand, consisted of all mature components and, therefore, represented a mature cystic teratoma [Figure 4d-f]. The nodules in the uterine serosa, rectal peritoneum, and omentum were composed of mature, predominantly gliomatosis admixed with adipose tissue [Figure 5a-d], which occurs in about one-third of the cases with immature teratoma.[9]

- A 32-year-old woman presenting with progressively worsening abdominal pain subsequently diagnosed with bilateral teratomas (immature and mature). Two separate teratomatous areas (a-b and c-d) in the left ovary include neurotubules (black arrow) and neuroepithelial rosettes (white arrow). (Original magnification: (a,c): ×100; (b,d): ×400).

- A 32-year-old woman presenting with progressively worsening abdominal pain subsequently diagnosed with bilateral teratomas (immature and mature). Mature teratomatous components in the left ovary (a-c) and right ovary (d-e) include skin appendages (a, white arrow), cartilage (e), thyroid glands (d, arrow head), and respiratory epithelia (b,c,f, black arrow) (Original magnifications: ×100).

- A 32-year-old woman presenting with progressively worsening abdominal pain subsequently diagnosed with bilateral teratomas (immature and mature). Nodules in the rectal peritoneum (a,b) and omentum (c,d) were composed of mature glia tissue with bland looking glial cells (black arrow) forming nodules (white arrow). (Original magnification: a,c: ×100; b,d: ×400)

The patient’s serum sodium returned to normal 24 h after surgery and stabilized at about 138 mEq/L. The final diagnosis was FIGO Stage 1A Grade 2 immature teratoma, and the patient started 4 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin. Since her surgery, there has been no evidence of recurrent disease and her tumor markers have stabilized at normal levels. The patient has not shown symptoms or objective evidence of recurrent hyponatremia, as well.

CASE DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, there have been few reports of bilateral teratomas in the literature, and this is the first report of concurrent mature and immature teratomas including both ovaries with peritoneal gliomatosis, as confirmed on histopathology. Moreover, this case represents a rare instance of ovarian teratoma with hyponatremia refractory to medical management, which improved following tumor resection.

While teratomas are often detected as an incidental finding during the physical examination, imaging, or pelvic surgery, the most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain, occurring in about 44% of cases.[10,11] Furthermore, patients may present with symptoms of ovarian torsion, the most common complication of teratomas, which can occur in up to 16% of cases.[12] Other complications precipitating patient symptoms and clinical presentation include rupture (1–4%), malignant transformation (1–2%), and infection (1%).[13] Although our patient reported abdominal pain, she presented relatively insidiously with symptoms secondary to mass effect (nausea, early satiety, urinary frequency, and constipation), which more commonly characterize other ovarian neoplasms, such as epithelial ovarian cancer.

Of note, this case is one of the only reported examples of patients presenting with refractory hyponatremia that resolves after ovarian teratoma resection. Specifically, there are at least four cases reported regarding immature teratomas presenting with hyponatremia resistant to medical management with subsequent resolution following surgical removal of the tumor.[13] Accordingly, it is possible that this case presents further evidence for the possible presence of a paraneoplastic, SIADH-like syndrome involving a substance released by the ovarian tumor. However, the both pre- operative and post-operative vasopressin levels were not measured, preventing definite conclusion that the patient’s hyponatremia was secondary to a vasopressin-like substance versus vasopressin released from the body in response to nausea and pain or from the tumor itself.

On CT or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, mature cystic teratomas are most often characterized by a cystic mass with a low-density area of intratumoral fat.[14,15] The presence of calcification further supports the diagnosis of a ovarian teratoma; however, this finding is not exclusive and may be seen with other ovarian neoplasms.[14] Although immature teratomas may appear similar to benign, mature teratomas on imaging, the presence of a heterogeneous mass containing a solid component interspersed with cystic areas and intratumoral fat is highly suggestive of an immature teratoma.[14] Furthermore, as in this case, immature teratomas typically have a larger diameter than mature cystic teratomas (mean 12–25 cm compared to 7 cm, respectively).[14,16]

As observed in our patient, chronic rupture of an ovarian teratoma may result in chronic granulomatous peritonitis (i.e., gliomatosis).[2] The presence of adhesions noted on gross pathology further supports this finding, as adhesions may form following chronic recurrent peritonitis and predispose patients to future complications, including small bowel obstruction.[14] Imaging findings supporting the diagnosis of tumor rupture include ascites, omental infiltration, and abdominal inflammatory masses, which may appear similar to peritoneal carcinomatosis as noted on our patient’s imaging reports.[14] Additional evaluation should include assessment for any discontinuity of the tumor wall and perceived distortion, or flattening of the tumor, which further suggests rupture.[14]

CONCLUSION

Immature teratomas may occur concurrently with mature teratomas and demonstrate heterogeneous appearance on CT and MR images, characterized by a solid component with interspersed cystic areas and intratumoral fat, as opposed to mature cystic teratomas, which lack a prominent solid component and tend to be smaller in diameter. Secondary signs suggesting malignant transformation or rupture may also be present, including chronic granulomatous peritonitis (gliomatosis), which may appear as ascites, omental infiltration, and inflammatory masses on imaging, similar to peritoneal carcinomatosis. Although ovarian teratomas are associated with torsion, rupture, malignant transformation, and infection, they may present insidiously with symptoms secondary to mass effect.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bilateral ovarian angiosarcoma arising from the mature cystic teratomas-a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;42:90-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atypical CT and MRI manifestations of mature ovarian cystic teratomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:743-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laparoscopic resection of ovarian benign cystic teratomas: Experience with 84 cases. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1810-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Three cases of immature teratoma diagnosed after laparoscopic operation. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2014;7:91-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilateral immature ovarian teratoma in a 12-year-old girl: A case report. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2012;58:138-40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Germ cell tumors and mixed germ cell-sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary In: Zheng W, Fadare O, Quick CM, Shen D, Guo D, eds. Gynecologic and Obstetric Pathology. Vol 2. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. :231-71.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gliomatosis peritonei is associated with frequent recurrence, but does not affect overall survival in patients with ovarian immature teratoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;461:299-304.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mature cystic teratoma: A clinicopathologic evaluation of 517 cases and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:22-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign cystic teratomas of the ovary; a clinico-statistical study of 1,007 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1955;70:368-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ovarian dermoids and their complications. Comprehensive historical review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1975;30:1-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immature ovarian teratoma with hyponatremia and low serum vasopressin level. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2016;42:1400-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging findings of complications and unusual manifestations of ovarian teratomas. Radiographics. 2008;28:969-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mature and immature ovarian teratomas: CT, US and MR imaging characteristics. Eur J Radiol. 2009;72:454-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An intense clinicopathologic study of 305 teratomas of the ovary. Cancer. 1971;27:343-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]