Translate this page into:

Broad Ligament Fibroid Mimicking as Ovarian Tumor on Ultrasonography and Computed Tomography Scan

Address for correspondence: Dr. Dayananda Kumar Rajanna, No.124/2, Hosahalli, Hunasamaranahalli, Bangalore - 562 114, Karntaka State, India. E-mail: drkrdayanand@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Giant fibroids are known to arise from the uterus, and very rarely from the broad ligament. Large fibroids often undergo hyaline, cystic, and at times, red degeneration. In the present case, cystic degeneration with intervening septations in an adnexal mass raised the suspicion of ovarian neoplasm as the ovaries were not seen as separate from the lesion. The ultrasonographic and contrast-enhanced computed tomographic findings of this case were characteristic of ovarian neoplasm. The differential diagnosis included rare possibility of giant fibroid with cystic degeneration. The diagnosis was confirmed on histopathological examination. The patient underwent excision of the broad ligament fibroid, hysterectomy, and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Magnetic resonance imaging has a role in the diagnosis of such lesions.

Keywords

Broad ligament

computed tomography scan

fibroid

ultrasonography

INTRODUCTION

Fibroid or leiomyoma is the commonest of all uterine tumors. They are most common in women of child-bearing age. Their classification is determined by their origin and direction of growth. They are divided into three main groups subserous, interstitial, and submucous. Submucous fibroids arise beneath the endometrial layer and often project into endometrial cavity, interstitial or intramural fibroids arise within the myometrium, and subserous fibroids arise from serosal layer and present as adnexal masses. Extra-uterine fibroids do occur but are not as common as uterine fibroids. Extra-uterine fibroids may develop in the broad ligament or at other sites where smooth muscle exists.[1] Common symptoms of fibroids include menstrual disturbances, dysmenorrhea, and symptoms related to pressure caused by the mass.[2] Most common secondary changes are degeneration, infection, hemorrhage, necrosis, and rarely, sarcomatous changes.

CASE REPORT

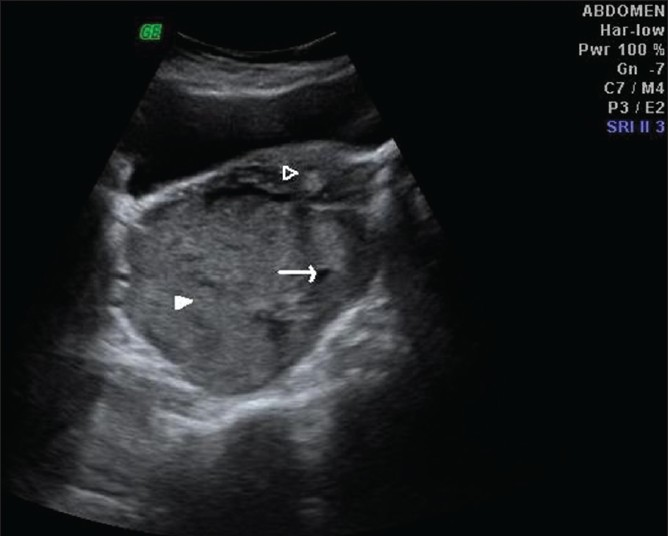

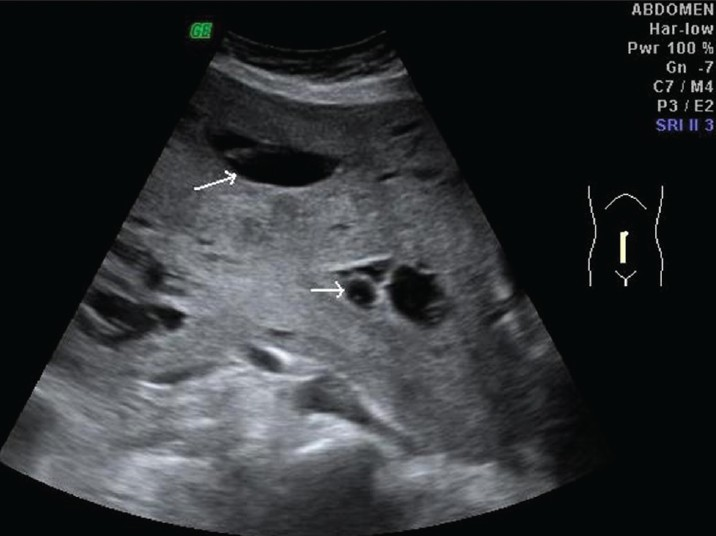

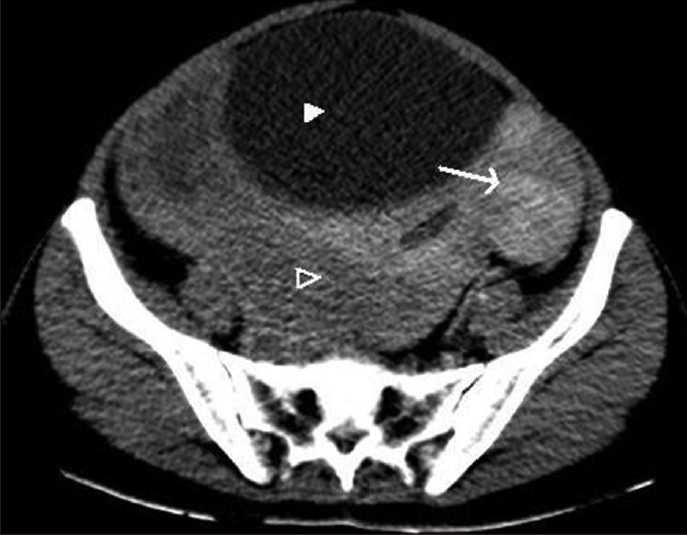

A 40-year-old nulliparous lady, married for 23 years, came with a 6-month history of abdominal discomfort. She had no history of bowel or bladder complaints, weight loss, anorexia, or fever. Previous menstrual cycles were regular. On examination, the patient was afebrile, pulse 76/min, and blood pressure 130/80 mmHg. Abdominal examination revealed a mass of 24-26 weeks size gravid uterus, which appeared to be arising from the pelvis. On palpation, mass was of found to vary in consistency, non-tender, transversely mobile with irregular margins. The lower pole could be reached partially. On speculum examination, cervix could not be visualized, and no abnormal discharge was seen. On vaginal examination, the mass was felt in the pouch of Douglas pushing the cervix anteriorly. Forniceal fullness was present and it was non-tender. Routine blood analysis was within normal limits. Serum Human chorionic gonadotropin values were <0.10 milli international units per liter. Serum CA-125 (cancer antigen 125) value was 28 milli international units per liter. On ultrasonography, a well-defined, mixed echogenic lesion measuring 22 cm × 12.2 cm × 18.6 cm was seen in the midline posterior to bladder pushing the uterus anterolaterally toward the left side [Figure 1], extending cranially up to mid-abdomen with multiple internal cystic changes [Figure 2]. There was moderate to gross internal vascularity. Minimal fluid with internal echoes was noted in the endometrial cavity. There were two fibroids measuring 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm and 3 cm × 3 cm in the anterior and left lateral wall respectively. The right ovary was not seen as separate from the mass. Left ovary was normal. There was mild hydroureteronephrosis in the right kidney likely due to ureteric obstruction by the right adnexal mass. Diagnosis of right ovarian neoplasm was made. On contrast-enhanced computed tomographic (CECT) scan of abdomen and pelvis, a large mixed density abdomino-pelvic lesion was seen in the pouch of Douglas with thick internal septations and solid components [Figure 3]. The septations and solid components showed significant enhancement on postcontrast images [Figure 4]. The CECT appearance was typical of cystic ovarian neoplasm. Final diagnosis based on the CECT scan of abdomen and pelvis was right ovarian neoplasm.

- Trans-abdominal ultrasonogram in a 40-year-old woman at the level of urinary bladder shows mixed echogenic, predominantly hyperechoic lesion in pouch of Douglas displacing the uterus (empty arrowhead) anteriorly and cystic (arrow) and solid components (solid arrowhead) within the lesion.

- Longitudinal scan reveals cranial extension of lesion up to umbilicus with multiple internal cystic components (arrows).

- Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan section at the level of urinary bladder (solid arrowhead) shows displacement of uterus anterolaterally (arrow) and mixed density mass posteriorly (empty arrowhead).

- Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan at a higher level reveals thick enhancing septae (arrowheads) and cystic components (arrow).

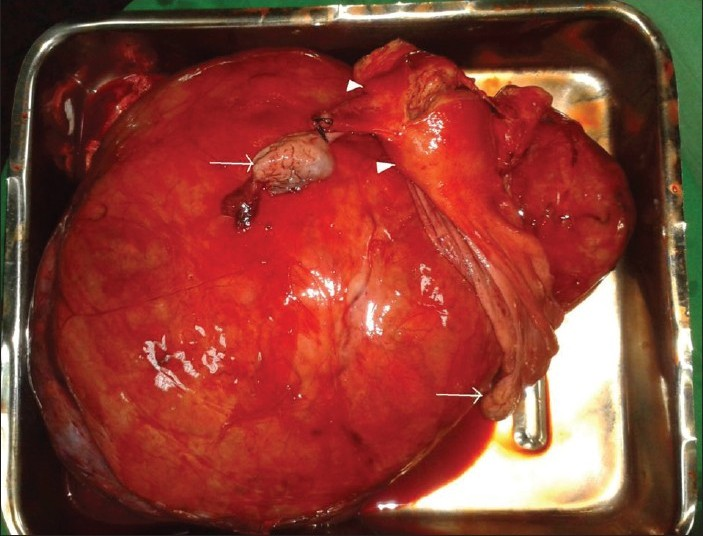

With a provisional diagnosis of malignant ovarian tumor, the patient was taken up for an exploratory laparotomy. Intra-operatively, an abdomino-pelvic mass of size approximately 24 cm × 18 cm × 8 cm was seen with variable consistency and increased vascularity, arising from the right side of the uterus pushing the ureter laterally. Right fallopian tube, ovarian ligament, and round ligament stretched over the mass. Right ovary was normal. Left tube and ovary were normal. The mass was loosely adherent to the small bowel loops. Two fibroids in the fundus of uterus measuring 2 cm × 2 cm and 3 cm × 2 cm and 5-6 seedling fibroids were noted per-operatively. As the tumor was distorting the pelvic anatomy, careful dissection was done to prevent ureteric injuries. Excision of tumor with total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was done. Post-operative course was uneventful.

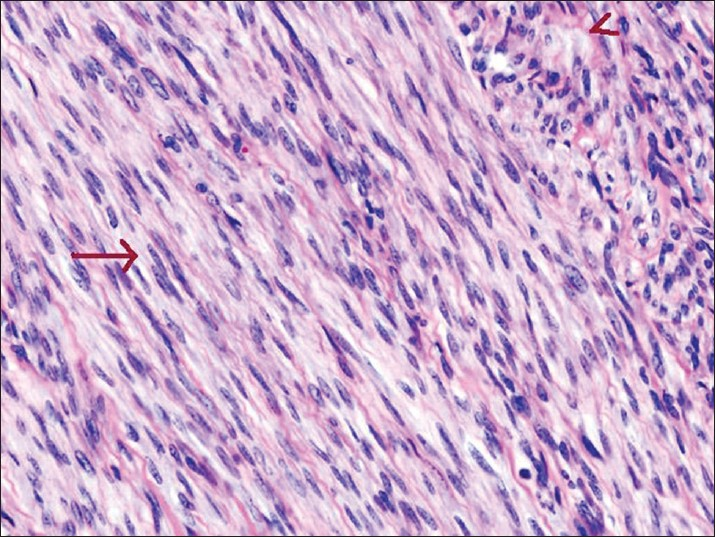

The surgically resected specimen included a large nodular cystic mass measuring 25 cm × 25 cm × 8 cm adjacent to the uterus in the right broad ligament with bilateral normal ovaries [Figure 5]. On histopathological examination, the cut section of the mass showed solid fleshy areas and cystic areas filled with hemorrhage. The uterus revealed two large and multiple small intramural fibroids. The largest one measured 4 cm × 5 cm and smallest 0.5 cm in diameter. Right fallopian tube was stretched and measured 14 cm and right ovary was 3.5 cm × 1.5 cm × 0.5 cm. Cut section of ovary showed cyst filled with serous fluid. Cyst measured 2 cm in diameter. The ligamentous membranous attachment to the lesion seen on the right side was noted to be the broad ligament. Left fallopian tube was 3.5 cm. The mass in the broad ligament stained with hematoxylin and eosin showed the endo-myometrium was composed of round to oval glands lined by columnar epithelium set in a compact stroma. Section studied from the larger parametrial mass showed a benign tumor with interlacing bundles of smooth muscle cells, scattered thick-walled blood vessels, and evidence of cystic, myxoid and hyaline degeneration [Figure 6]. Cervix showed a mild-to-moderate sub-epithelial lymphocytic infiltrate. There was no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy in the cut sections of the cervix. The final histopathological report was:

-

Proliferative phase endometrium

-

Leiomyoma: Intramural and parametrial (mass arising adjacent to the uterus)

-

Chronic cervicitis

-

Bilateral adnexa with no significant pathology

- Gross surgically removed specimen of giant fibroid in the right broad ligament with normal ovaries (arrows) and uterus (arrow head).

- Microscopic examination of the surgically removed specimen found in the right broad ligament demonstrates interlacing bundles of smooth muscle cells (arrow), scattered thick walled blood vessels, and evidence of cystic, myxoid, and hyaline degeneration (arrowhead) (Hematoxylin and eosin, ×100)..

DISCUSSION

Occasionally, fibroids become adherent to surrounding structures like the broad ligament, omentum, develop an auxiliary blood supply and lose their original attachment to the uterus. It has also been suggested that fibroids that are adherent to the broad ligament originate from hormonally sensitive smooth muscle elements of that ligament. Clinically, these lesions may manifest as extrauterine pelvic masses that compress the urethra, bladder neck, or ureter producing symptoms of varying degrees of urinary outflow obstruction or secondary hydroureteronephrosis. On ultrasound, a typical leiomyoma usually has a whorled appearance, with variable echogenicity depending on the extent of degeneration, fibrosis, and calcification.[3] The differential diagnosis for broad ligament fibroids includes masses of ovarian origin (both primary neoplasms and metastasis), broad ligament cyst, and lymphadenopathy. Transvaginal ultrasound may be of help in diagnosing broad ligament fibroid because it allows clear visual separation of the uterus and ovaries from the mass. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with its multiplanar imaging capabilities, may be extremely useful for differentiating broad ligament fibroids from masses of ovarian or tubal origin and from broad ligament cysts. The distinctive MRI appearances of typical fibroids also are useful in differentiating them from solid malignant pelvic tumors. This observation is important because broad ligament fibroids are associated with pseudo-Meigs syndrome and produce an elevated cancer marker CA-125 levels that may point to metastatic ovarian carcinoma, thereby causing diagnostic confusion. Typical fibroids demonstrate low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Myxoid degeneration and necrosis may be visible as high signal intensity areas on T2-weighted images. Another common variant seen on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images is a cobblestone-like appearance due to hyaline degeneration, with high signal intensity foci representing areas of infarction due to rapid growth. Hyalinization is the most common type of degeneration occurring in 60% of cases. Cystic degeneration occurs in 4% of cases and is considered an extreme sequel of edema.[4] Kaushik et al.,[5] have reported series of two cases of uterine fibroids with cystic degeneration. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy of the tumor may be helpful for determining its exact histologic composition before surgery. Cystic lesions in female pelvis most often originate in the ovary. Non-ovarian cystic pelvic lesions may include peritoneal inclusion cysts, paraovarian cysts, mucocele of appendix, hydrosalpinx, subserosal, or broad ligament leiomyomas with cystic degeneration, cystic adenomyosis, cystic degeneration of lymph nodes, hematoma, abscess, spinal meningeal cysts, and lymphoceles.[6] Four percent of fibroids undergo cystic degeneration with extensive edema forming cystic, fluid-filled spaces. In such cases, vessels bridging the mass and the myometrial tissue, termed bridging vessel sign is useful in diagnosing the case as leiomyoma.

CONCLUSION

Extra-uterine fibroids occur infrequently, although they are histologically benign, may mimic malignant tumors at imaging, and may present a diagnostic challenge. The clinical symptoms and imaging features depend on the location of the lesion and on its growth pattern. So, the differential diagnosis of extra-uterine fibroid should be considered in cases of pelvic masses with normal uterus and ovaries.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2013/3/1/8/107912

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Tumors of the corpus uteri. In: Jeffcoate's Principles of Gynaecology (7th ed). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2008. p. :492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign diseases of the female reproductive tract. In: Novack's Gynaecology (15th ed). New Delhi: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Wolters Kluwer (India); 2007. p. :470.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leiomyomas beyond the uterus: Unusual locations, rare manifestations. Radiographics. 2008;28:1931-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of cystic leiomyoma mimicking an ovarian malignancy. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33:371-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Case series: Cystic degeneration in uterine leiomyomas. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2008;18:69-72.

- [Google Scholar]