Translate this page into:

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for pediatric portal hypertension: A meta-analysis

*Corresponding author: Driss Raissi, Department of Radiology, Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Kentucky, College of Medicine, Lexington, United States. driss.raissi@uky.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Raissi D, Brahmbhatt S, Yu Q, Jiang L, Liu C. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for pediatric portal hypertension: A meta-analysis. J Clin Imaging Sci 2023;13:18.

Abstract

To evaluate the feasibility of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in children with portal hypertensive complications, PubMed and Cochrane Library were queried to identify clinical studies evaluating TIPS in patients <18 years old. Baseline clinical characteristics, laboratory values, and clinical outcomes were extracted. Eleven observational studies totaling 198 subjects were included in the study. The pooled technical success rate and hemodynamic success rate were 94% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 86–99%) and 91% (95% CI: 82–97%), respectively; ongoing variceal bleeding resolved in 99.5% (95% CI: 97–100%); refractory ascites was improved in 96% (95% CI: 69–100%); post-TIPS bleeding rate was 14% (95% CI: 1–33%); 88% of patients were alive or successfully received liver transplant (95% CI: 79–96%); and shunt dysfunction rate was 27% (95% CI: 17–38%). Hepatic encephalopathy occurred in 10.6% (21/198), though 85.7% (18/21) resolved with medical management only. In conclusion, based on moderate levels of evidence, TIPS is a safe and effective intervention that should be considered in pediatric patients with portal hypertensive complications. Future comparative studies are warranted.

Keywords

Children

Interventional radiology

Stent

Variceal bleed

Ascites

INTRODUCTION

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is a well-established procedure to treat gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) and refractory ascites in adults with portal hypertension (pHTN) secondary to cirrhosis.[1,2] However, evidence supporting the use of TIPS in the pediatric population remains scarce. Surgical shunt is often used in treating medically refractory pHTN in the pediatric population, with pre-hepatic etiology treated with the creation of meso-Rex shunt and intrahepatic etiology treated with surgical portosystemic shunts.[3,4] However, compared to TIPS, surgery is a more invasive option in the setting of acute variceal GIB and cannot be applied to every patient due to anatomical and technical limitations.[5] TIPS can serve as a bridge to transplant or simply be a palliative treatment if the latter is not an option.

The purpose of this study was to review and characterize the safety and effectiveness of TIPS in the pediatric population by conducting a meta-analysis.

METHODS

The Cochrane Database and PubMed were queried from the establishment to October 2020 with the following keywords: “Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt” AND (“child” OR “pediatric”). The following criteria were adopted: (1) Patients <18 years old received TIPS; (2) sample size ≥5; (3) free full-text available; and (4) studies with original data. The following data were extracted by two researchers: study name, year of publication, region, patient number, sex, age, indication of TIPS, pHTN etiology, TIPS stent type, laboratory values, technical success, hemodynamic success, immediate clinical success, post-TIPS bleeding rate, survival/mortality, shunt patency, and complications. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion. The following terms are defined:

Technical success: successful placement of TIPS

Hemodynamic success: reduction of portosystemic gradient (PSG) <12 mmHg

Immediate clinical success: resolution of ongoing-GIB or improvement of existing ascites

Post-TIPS bleeding: recurrence of or de novo GIB after successful TIPS placement

Survival: successful bridging to transplant or alive with native liver at follow-up

Shunt-dysfunction: shunt stenosis or thrombosis requiring intervention to maintain patency.

Statistical analysis was performed with STATA 15.1 (STATA Corp., College Station, TX). Pooled analysis was conducted with the-metaprop_one function. A random-effects model was used. Technical success, hemodynamic success, immediate clinical success, post-TIPS bleeding rate, survival, and shunt dysfunction were reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

RESULTS

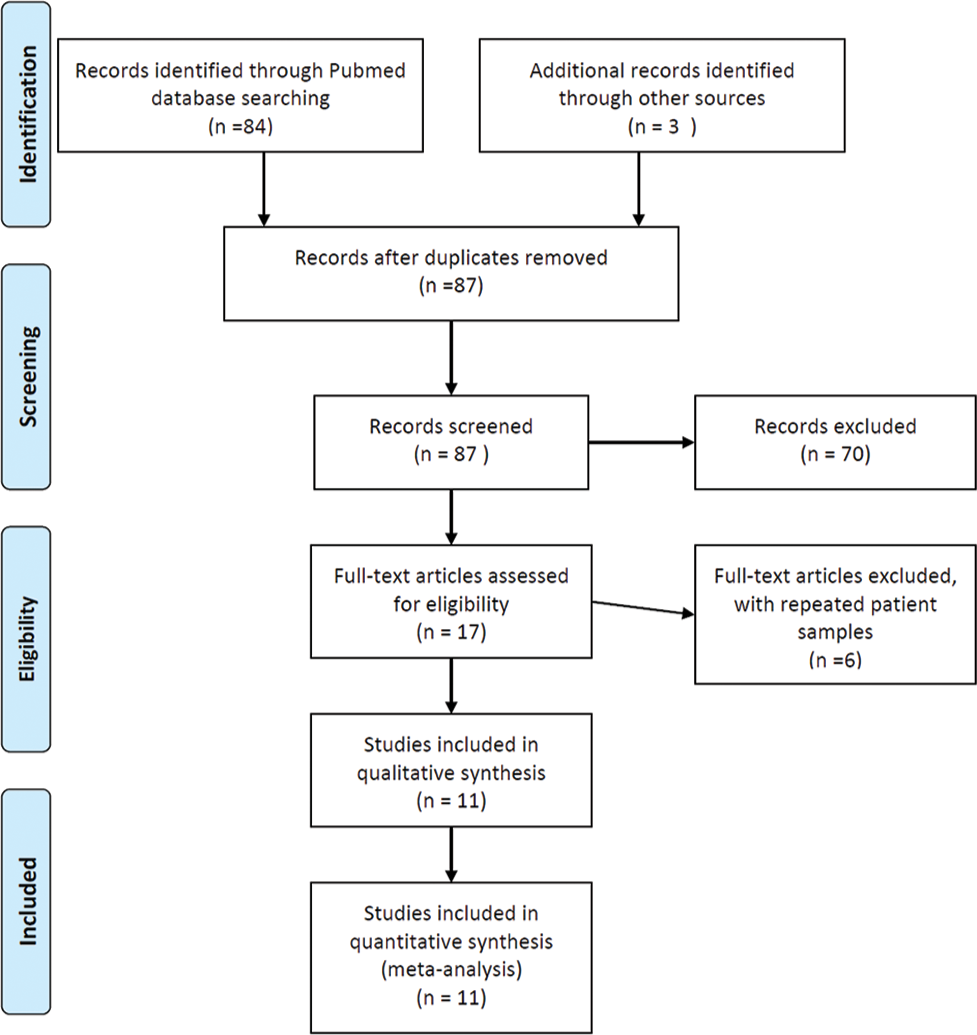

Among the initial 236 search results, 11 unique studies published from 1997 to 2019 were included in the meta-analysis.[6-16] [Figure 1] Of note, for studies with repeated patient samples, the most recent study was included in the study; Slowik et al. have included instead of Bertino et al., because the latter did not report outcomes of the pediatric subgroup (age<18) separately.[6,17] The majority of published studies were conducted in the US and Europe; only two studies were from Asia [Table 1].

- Literature search and screening process.

| No. Study | Study/Year | Region | Pt No. (F:M) | Average age in years (range) | Average weight in kg (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zurera et al. 2015 | Spain | 12 (3:9) | 9 (2–16) | 30 (11–60) |

| 2 | Sharma et al. 2016 | India | 14 (6:8) | 5.4 (0.5–17.8) | N/A |

| 3 | Lv et al. 2015 | China | 17 (7:10) | 12.3 (7.1–17.9) | 33 (19–55) |

| 4 | Johansen et al. 2018 | UK | 40 (20:20) | 10.7 (0.6–17.2) | 38.3 (6.4–77.9) |

| 5 | Hackworth et al. 1997 | USA | 12 (6:6) | 9.5 (2.4–16.8) | 34.14 (13.9–80.9) |

| 6 | Ghannam et al. 2018 | USA | 21 (9:12) | 12.1 (2–17) | N/A |

| 7 | Di Giorgio et al. 2019 | Italy | 27 | 10.3 | 36.7 |

| 8 | Slowik et al. 2019 | USA | 31 (20:11) | 11.5 (1–17) | 39.4 (11.8–90.6) |

| 9 | Huppert et al. 2002 | Germany | 9 | 8.1 (2.8–12.6) | NA |

| 10 | Heyman et al. 1997 | USA | 9 (5:4) | 9.4 (5–15) | 31.2 (16–70) |

| 11 | Verbeeck et al. 2018 | Belgium | 5 (3:2) | 9.2 (4.7–14.3) | 33.3 (16–77.4) |

N/R: Not reported, Pt: Patient number, No.: Number

A total of 198 pediatric patients underwent the TIPS procedure, and 49.1% were female in reported studies (79/161). The median age of included patients was 10.3 years, ranging from 0.5 years to 17.9 years and the median weight was 30 kg, ranging from 6.4 kg to 90.6 kg. The patient characteristics of individual study are reported in [Table 1].

Biliary atresia is the most common etiology 21% (Table 2, 42/198). TIPS placement was technically successful in 94% of cases (Figure 2a, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 86–99%). The mean PSG before TIPS was 20.9 mmHg and the mean post-PSG was 9.7 mmHg with each study listed in [Table 2]. In 91% of all cases, PSG was successfully reduced to <12 mmHg (Figure 2b, 95% CI: 82–97%). Ongoing GIB resolved in 99.5% of patients after TIPS (Figure 2c, 95% CI: 97–100%), whereas refractory ascites improved in 96% of patients (Figure 2c, 95% CI: 69–100%). GIB occurred in 1of 4% patients after TIPS placement (Figure 2d, 95% CI: 1–33%). With a mean/ median follow-up ranging from 135 days to 12.5 years, the survival rate was 88% (Figure 2e, 95% CI: 79–96%). Among a total of 148 patients that survived, 32.4% (n = 48) underwent liver transplant, with the rest of the patients surviving with their native liver. Shunt dysfunction occurred in 27% of the cases (Figure 2f, 95% CI: 17–38%) with a median time to reintervention of 14 months for non-acute shunt dysfunction (ranges 24 days to 10 years).[7-10,12,15,16] The reported rate of acute shunt dysfunction occurring within the first 48 h is 3.8% (3/78).

| Study | Indication (n) | Stent | Etiology (n) | Stent width, (mm) | Stent dilation, (mm) | Pre PSG (mean±SD) | Post PSG (mean±SD) | Follow-up (Months/Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zurera et al. 2015 | GIB (12) | Viatorr (W.L. Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, AZ) |

Biliary atresia (3) Cystic fibrosis (2) Congenital hepatic fibrosis (1) Caroli disease (1) Ductopenia (1) Cirrhosis of unknown origin (1) Liver transplant (1) Thrombosis and cavernomatosis (2) |

10 | 6–10 | 15.5±5.4 | 7.5±3.3 | Mean: 22 months | |

| Sharma et al. 2016 | N/A | N/A | Budd-Chari (14) | NR | NR | 23.7±5.5 | 3.3±1.3 | Median: 44 months | |

| Lv et al. 2015 | N/A | Fluency Bard, (Karlsruhe, Germany) Smart Cordis, (Miami, FL); Protégé GPS EV3, (Plymouth, MN) |

Extrahepatic portal venous obstruction (17) | 8–10 | 8–10 | 26.4±4.5 | 10.9±4.3 | Median: 36 months | |

| Johansen et al. 2018 | GIB (35) Ascites (4) HSP (1) |

Viatorr (WL Gore, UK) Wallstent (Schneider, UK) |

Biliary atresia (12) Cystic fibrosis (8) Intestinal failure associated liver disease (4) Budd Chiari (3) Autoimmune (3) Drug induced liver injury (2) Cryptogenic (2) Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (2) Others (4) |

7–10 | 6–10 | 27.7±8.1 | 19.3±6.7 | Mean: 6.2 years | |

| Hackworth et al. 1997 | GIB (12) Ascites (2) |

Wallstent (Schneider, Minnetonka, Minn). |

Congenital hepatic fibrosis biliary atresia Autoimmune hepatitis Post-transplant hepatitis C Chronic allograft rejection Portal angiodysplasia Langerhans cell histiocytosis Alpha-antitrypsin deficiency |

5–12 | 6–12 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Ghannam et al. 2018 | GIB 20 Ascites (1) |

Viatorr (W.L. Gore and Associates, Newark, DE) Wallstent (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) Express (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA) iCast (Atrium Medical, Hudson, NH) |

Biliary atresia (5) Cryptogenic cirrhosis (4) Porta/hepatic vein thrombosis (4) Polycystic kidney disease (3) Primary sclerosing cholangitis (2) Other (3) |

5–12 | 6–10 | 18.5±10.7 | 7.1±3.9 | Mean: 65 months (without liver transplant); Mean: 15.9 months (from TIPS placement to liver transplant) |

|

| Di Giorgio et al. 2019 | GIB (17) Ascites (11) |

Viator (W.L. Gore, Flagstaff, AZ) Memotherm (Bard Angiomed Ltd, Crawley, UK |

Biliary atresia (3) Cystic fibrosis (3) Intestinal failure associated liver disease (2) Primary sclerosing cholangitis (1) Intrahepatic cholestasis (1) Liver Transplant (2) Budd Chiari (8) Portal vein thrombosis (5) Ductal plate malformation (3) Hepatoportal sclerosis (1) |

8–10 | 7–8 | 19.5±6 | 8±2.5 | Median: 12.5 years | |

| Slowik et al. 2019 | GIB (26) Ascites (2) Thrombosis (2) Splenic sequestration (1) |

N/A | Cavernous transformation (6) Congenital fibrosis (4) Biliary atresia (5) Cystic Fibrosis (3) Nodular regenerative hyperplasia (1) Zellweger syndrome (1) Autoimmune hepatitis (2) Primary sclerosing cholangitis (1) Fibrotic liver disease of unknown etiology (1) Veno-occlusive (1) Berardinelli-Seip syndrome (1) Chronic rejection of liver transplant (1) Splanchnic thrombosis of portal venous system (1) Glycogen storage 1b (1) Parenteral nutrition related liver disease (1) Hepatoportal sclerosis (1) |

6–10 | 6–10 | 14.5±4.9 | 4.3±2.7 | Mean: 24 months | |

| Huppert et al. 2002 | GIB (9 one also has ascites) | Wallstent (Schneider, UK) Palmaz Cragg (MinTec, Freeport, Bahamas) |

Biliary atresia (9) | 6–9 | NR | 17.4±4.6 | 9.4±2.2 | Mean: 69.6 months | |

| Heyman et al. 1997 | GIB (7) Hypersplenism (2, with one also has ascites) |

Wallstent (Scheider, USA) |

Cryptogenic cirrhosis (2) Biliary Atresia (4) Congenital hepatic fibrosis (1) Primary sclerosing cholangitis (1) Coach syndrome (1) |

6–8 | 6–10 | N/A | N/A | Mean: 4.5 months | |

| Verbeeck et al. 2018 | GIB (5) | Wallstent (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) Viatorr (WL Goreand Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) |

Polycystic kidney disease related liver fibrosis (5) | 8 | 8 | 17.6±4.4 | 6±2.9 | Mean: 7.2 years | |

N/R: Not reported, N/A: Not available, GIB: Gastrointestinal bleed, HSP: Henoch-Schonlein purpura, PSG: Porto-systemic gradient, SD: Standard deviation

- Meta-analysis results: (a) technical success, (b) hemodynamic success, (c) immediate clinical success, (d) post-tips gastrointestinal bleeding, (e) post-tips survival, and (f) shunt dysfunction rate.

Whereas earlier studies only used bare metal stents, both covered and non-covered stents were used in more recent studies. Viatorr (Gore, USA/UK) and Wallstent (Boston Scientific, USA/Schneider, UK) were the most commonly used stents [Table 2]. In terms of complications, hepatic encephalopathy (HE) was the most frequent, observed in 10.6% of patients (n = 21). The majority of patients (n = 18) with HE were treated successfully with medical management. Two HE patients reported in Johansen et al. were refractory to medical treatment, and one of them required staged closure of TIPS to relieve symptoms. Other etiologies included hemoperitoneum (n = 2), capsular hematoma (n = 2), bile leak (n = 1), arteriovenous fistula (n = 1), and endotipsitis (n = 1). Platelet count, spleen size, albumin, blood ammonia, and total bilirubin were also reported by selected studies [Table 3].

| Study/Year | Platelet (×109/L) | Spleen size (cm) | Albumin (g/dl) | Ammonia (umol/L) | Bilirubin (mg/dL) | Complications (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||

| Zurera et al. 2015 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Mild HE (1) (resolved with lactulose) – 8.3% |

| Sharma et al. 2016 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Hemopericardium with nephropathy (1) |

| Capsular hematoma (1) | |||||||||||

| AV fistula with haemobilia (1) | |||||||||||

| Lv et al. 2015 | 59.5 | 75 | 17.5 | 19 | - | - | - | - | - | - | Capsular hematoma (1) |

| Johansen et al. 2018 | 98.3 | 133.5 | 16.4 | 14.6 | - | - | 50.8 | 114.6 | - | - | HA thrombosis/liver infarction/sepsis, (1) |

| Pseudoaneurysm of HA (1) | |||||||||||

| Bile leak, (1) | |||||||||||

| HE (3) (2 refractory to medical management) – 7.5% | |||||||||||

| Hackworth et al. 1997 | 96.4 | 98.7 | - | - | 3.4 | 3.3 | - | - | 5.1 | 10.0 | HE (1)–managed with lactulose (8.3%) |

| Pulmonary edema resolved with diuretic (1) | |||||||||||

| Access site minor hematoma (1) | |||||||||||

| Ghannam et al. 2018 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Increased at 2 mo and decreased at 1 year | HE (10)–successfully treated with medication. (47.6%) | |

| Di Giorgio et al. 2019 | 133 | 146 | 16.2 | 15.5 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 46 | 69 | 1.2 | 2.2 | No HE |

| Slowik et al. 2019 | No difference | - | - | No difference | Weak increase | - | - | HE (5)–managed medically (16.1%) | |||

| Huppert et al. 2002 | 81.7 | 84.4 | 14 | 14.8 | - | - | 91.1 | 96.9 | 2.1 | 3.1 | HE (1)–persisted until transplant (11.1%) |

| Heyman et al. 1997 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | No HE. |

| Hemoperitoneum (1) | |||||||||||

| Verbeeck et al. 2018 | 100 | 154 | 18.1 | 15.1 | - | - | 35 | 48 | - | - | No HE. |

HE: Hepatic encephalopathy, AV: Arteriovenous, HA: Hepatic artery

DISCUSSION

What is known

TIPSs are a well-established procedure commonly used in adults with pHTN to treat variceal GIB and refractory ascites

TIPS has been shown to be feasible in children in small retrospective cohort studies.

What is new

Our study demonstrates that TIPS is effective in achieving immediate clinical success and preventing future variceal bleeding in children

The risk of medically refractory HE is minimal

Our study shows the need for high-quality comparative studies of TIPS versus surgical bypass in the pediatric population.

Complications of pHTN can range from variceal bleeding, ascites to hepatorenal syndrome and thrombocytopenia.[2] There are two main categories behind the etiology of pHTN, intrahepatic and extrahepatic, with the former being the most common type in children.[3] The present meta-analysis covered a variety of primary diagnoses, such as biliary atresia, cystic fibrosis, congenital hepatic fibrosis, and Budd-Chiari syndrome [Table 1]. TIPS is a well-validated percutaneous intervention that can alleviate pHTN-related complications through the creation of a decompressive shunt between the portal venous and systemic venous systems.[2] Despite TIPS being standard-of-care in selected adult patients, there is limited evidence supporting its use in pediatric patients. Based on 11 retrospective cohorts, the present meta-analysis showed that TIPS is technically feasible and effective for managing pHTN in children.

Similar to the adult population, the most commonly encountered indications in the present meta-analysis were variceal bleeding and refractory ascites [Table 1]. All included patients with ongoing or recurrent variceal bleeding had already failed conservative medical and endoscopic management. In the acute setting, TIPS achieved nearly 100% immediate hemostatic success rate [Figure 2c]. Among the two patients who had continued variceal bleeding and hemoperitoneum post-TIPS, one patient was a 6-year-old female with biliary atresia who received a liver transplant on post-TIPS day 3, while the other patient was a 15-year-old male with Child-Pugh C cryptogenic cirrhosis with concurrent pulmonary and renal disease who succumbed to multisystem organ failure.[6,10] Recurrent or de novo GIB occurred in 14% of patients, most secondary to shunt stenosis or thrombosis [Figure 2d]. The cumulative TIPS dysfunction rate was 27%. The primary patency rate was 71–83% and 60–64% at 1 and 2 years, respectively, consistent with reported rates in both pediatric and adult demographic.[18,19] The adopted follow-up and surveillance algorithms mirrored those of the adult population: Doppler ultrasound at 1 week and every 3–6 months within the 1st year post-TIPS. All reported dysfunctions were successfully managed through standard shunt maintenance without reported complications. While the use of covered versus non-covered stents can affect shunt patency, study-level subgroup analysis of such matter was not possible, as most individual studies included both types of stents.

According to Trebicka et al., the effectiveness of an 8 mm stent surpasses that of a fully or under dilated 10 mm stent, with no difference in shunt dysfunction rates and significantly lower HE complication rates.[20,21] Nonetheless, in younger children, dilating to 8 mm may still be too wide for successful treatment. Several retrospective studies have revealed positive outcomes resulting from under dilation of PTFE stents measuring up to 8 mm diameter with no accompanying elevations in complication risks.[22,23] While self-expandable stents can expand spontaneously and progressively which is beneficial especially for pediatric patients due to their rapid growth rate.[21,23,24] Schepis et al. indicated that this expansion effect does not occur when an 8 mm PTFE stent is under dilated. Hence, the optimal approach toward mitigating complications associated with these interventions would entail using “controlled-expansion” adjustable-diameter devices that lack inherent post-deployment expansion ability.[25,26] It is important to note that selection of stent depends on various other factors and data is not robust concerning the most appropriate diameter for a TIPS stent in a pediatric population.

Refractory ascites was the second most frequent indication among patients of the present study. Whereas 96% of ascites improved after TIPS placement, two patients had persistent mild symptoms controlled with diuretics. Less commonly, TIPS was performed in four cases to treat hypersplenism, a sequelae of pHTN associated with thrombocytopenia [Table 2]. An increase in platelet count and decreased splenic size was noted in several studies, though it was not consistently statistically significant [Table 3]. Other indications of TIPS, such as hydrothorax and hepatorenal syndrome, were not observed in the present study.

TIPS placement was technically successful in 94% of cases (Figure 2a, 95% CI: 86–99%) which are similar to that reported in adult population.[27,28] From a technical perspective, the creation of TIPS in children can be more technically challenging. On the one hand, these pediatric patients have a higher prevalence of hepatic vascular anomalies such as portal venous cavernous transformation and Budd-Chiari occlusive venous sequelae.[9,12] On the other hand, tools such as the standard TIPS kit were initially designed for adults. The size of the needle used in shunt creation can be rather large for younger and smaller children, leading to a high risk of iatrogenic trauma (i.e., hemoperitoneum). Tableside modifications of available tools and intravascular ultrasound have been used to increase technical success and minimize risks.[7,17] With careful manipulation, TIPS can be successfully deployed in patients weighing as low as 11 kg.[7] An additional consideration is a growth, although this patient population is notorious for predicted growth delay secondary to underlying liver disease. For patients with a predicted TIPS for longer than a year, an under-dilated endoprosthesis can be placed initially (i.e., using an 8 mm balloon to dilate a 10 mm endoprosthesis); based on physiological surveillance, future percutaneous adjustment can then be performed if needed.[12,15] Furthermore, because venous thrombosis can be more common in the pediatric population, preprocedural recanalization of the portal vein demands additional technical consideration before TIPS creation.[7,13] A variety of techniques may be needed for successful TIPS placement: secondary percutaneous access such as trans-splenic and transhepatic routes may be necessary and direct intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.[13] Nevertheless, operators should be cognizant of underlying pre-procedural hepatic vascular anatomy.

Despite the aforementioned technical challenges, TIPS is a safe procedure in the pediatric population with bleeding-related complications occurring in 2.7% (5/187) of pooled data, which is consistent with reported literature in the adult population.[29] In terms of long-term side effects, pediatric patients with pHTN are less likely to develop HE as compared to their adult counterparts (Incidence varies from 15% to 48%), this can be explained by the greater proportion of non-cirrhotic etiologies in children.[28] Although the blood ammonia level increased after TIPS placement in multiple studies, only 10.6% (21/198) developed HE. The majority (85.7%, 18/21) resolved with medical management alone.

The present study should be interpreted with caution. First, 10/11 studies are single-arm cohort and case series, which is considered level IV evidence and subject to selection bias. Comparative analyses between TIPS and other options, such as surgery or transplantation, were not performed, whereas its comparison with no TIPS could be difficult to perform for refractory GIB, as precluding a patient from receiving a life-saving intervention would be ethically challenging. Second, the patient population was rather heterogeneous, with a significant variety of primary diagnoses included in the study. Diseases such as Budd-Chiari syndrome are associated with a higher risk of thrombotic events, leading to an increased risk of future shunt dysfunction.[30] Yet, subgroup analysis based on each etiology was not possible due to the low quality of available patient-level data. Further, clinical outcomes were rarely reported based on time intervals. For example, TIPS patency and risk of HE likely increases as the follow-up interval increases, but only a few studies analyzed outcomes using Kaplan–Meier curves. In addition, the survival was poorly reported because many studies had a wide range of follow-up duration and did not include the specifics for individual patients. Noteworthy is the fact that the relationship between final PSG and clinical outcomes was not identified. In adults, a post-TIPS final PSG <12 mmHg or <10 mmHg is the recommended endpoint in the treatment of variceal bleeding and an even lower PSG may be needed for ascites management. By contrast, post-TIPS final PSG values remain generally undefined in children. Slowik et al. have shown that pediatric patients are still at risk of developing variceal bleeding, using adult PSG standard, while Bertino et al. demonstrated that a PSG <12 mmHg may be associated with promising clinical outcomes in the pediatric population.[6,17]

CONCLUSION

TIPS is technically feasible and effective in the treatment of refractory variceal bleeding and ascites in pediatric patients with pHTN, considering its nearly 100% early clinical success rate. In the long term, it is effective in the prevention of variceal bleeding recurrence with minimal risk of developing medically refractory HE. It is an accepted option for bridging to transplant and/or serving as a long-term management strategy for some pHTN complications such as ascites. In addition to comparative study designs of TIPS versus surgical bypass and given the significant underlying heterogeneity in this patient population, future multicenter studies are needed to increase sample size and obtain higher-level evidence in the pediatric population.

Acknowledgment

The authors’ would like special thanks to Chenyu Liu and Lan Jiang for their contribution to our project.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patients identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Predictors of hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhotic patients: A systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:943-51.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2005;41:386-400.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Management of portal hypertension in the pediatric population: A primer for the interventional radiologist. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2018;35:160-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The role of surgical shunts in the treatment of pediatric portal hypertension. Surgery. 2019;166:907-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experience with alternate sources of venous inflow in the meso-Rex bypass operation: The coronary and splenic veins. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1199-202.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pressure gradients, laboratory changes, and outcomes with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in pediatric portal hypertension. Pediatr Transplant. 2019;23:e13387.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safety and efficacy of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in children with acute or recurring upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Pediatr Radiol. 2015;45:422-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term clinical outcome of Budd-Chiari syndrome in children after radiological intervention. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:567-75.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for extrahepatic portal venous obstruction in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:233-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) in children. J Pediatr. 1997;131:914-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt insertion for the management of portal hypertension in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67:173-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation in children: Initial clinical experience. Radiology. 1998;206:109-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technical success and outcomes in pediatric patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement: A 20-year experience. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49:128-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in children with portal hypertension. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:615-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in children with biliary atresia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2002;25:484-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for portal hypertension in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:707-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Technical feasibility and clinical effectiveness of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation in pediatric and adolescent patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2019;30:178-86.e5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIPS for kids: Are we at the tipping point? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70:539.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patency of stents covered with polytetrafluoroethylene in patients treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: Long-term results of a randomized multicentre study. Liver Int. 2007;27:742-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eight millimetre covered TIPS does not compromise shunt function but reduces hepatic encephalopathy in preventing variceal re-bleeding. J Hepatol. 2017;67:508-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smaller-diameter covered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stents are associated with increased survival. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2793-9.e1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potential benefits of underdilation of 8-mm covered stent in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12:e00376.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Under-dilated TIPS associate with efficacy and reduced encephalopathy in a prospective, non-randomized study of patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:1153-62.e7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prospective evaluation of passive expansion of partially dilated transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stent grafts-a three-dimensional sonography study. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017;28:117-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt using the new gore viatorr controlled expansion endoprosthesis: Prospective, single-center, preliminary experience. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:78-86.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt reduction using the GORE VIATORR controlled expansion endoprosthesis: Hemodynamics of reducing an established 10-mm TIPS to 8-mm in diameter. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2018;41:518-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refractory ascites: Early experience in treatment with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Radiology. 1993;189:795-801.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt-related complications and practical solutions. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23:165-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for Budd-Chiari syndrome or portal vein thrombosis: Review of indications and problems. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:603-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]