Translate this page into:

Infantile Fibromatosis: A Rare Cause of Anterior Mediastinal Mass in a Child

Address for correspondence: Dr. Venkatraman Bhat, 309, Greenwoods Apartment, Royal Gardenia, Bommasandra, Bangalore - 560 099, Karnataka, India. E-mail: bvenkatraman@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Fibromatosis also known as desmoid tumor is an uncommon cause of a mediastinal mass in patients of all ages. Imaging appearance of fibromatosis is generally nonspecific and demands special attention to subtle details to be correctly identified as a possibility. Management of the patient is often complicated by failure to obtain precise pre-operative diagnosis. Location of a mass in the anterior mediastinum with encasement of vital structures is not favourable for complete cure. Although histologically benign, biological behaviour of the lesion varies between benign fibrous proliferation and low-grade fibrosarcoma. We present imaging appearances, surgical management dilemma, and the histopathological details of a case of fibromatosis in the anterior mediastinum in a child.

Keywords

Imaging

infantile fibromatosis

MDCT

mediastinal fibromatosis

INTRODUCTION

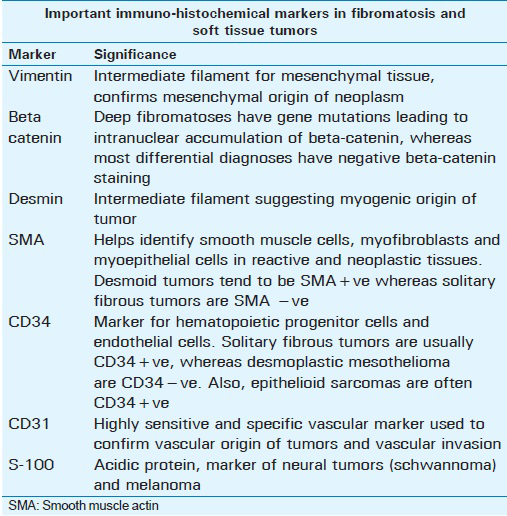

Mediastinal masses (MM) are relatively common in children. Mediastinal fibromatosis (MF) is one of the most uncommon causes of anterior MM.[1] This lesion has a tendency for local invasion, vascular encasement, and local recurrence. Imaging plays an important role in preoperative detection of the MM, their localization, and assessment of the airways. MDCT examination is the mainstay in the assessment of MM. Evaluation of encasement of important vascular structures and compression of the airway are critical to evaluate when a mediastinal mass is detected on imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers better tissue characterization and detects atypical MM with critical management issues. Imaging appearance of a homogeneous lesion with low T1 and T2 signals on MRI may suggest a fibroma with dense cellular structure. Being not able to identify this uncommon entity preoperatively may lead to repeat surgical procedures and suboptimal surgical outcomes. Fine needle aspiration is rarely effective. Core biopsy of the lesion may also not lead to specific diagnosis of the lesion unless immuno-histochemistry is performed. Specific diagnosis of fibroma is achieved by histopathology and immuno-histochemistry investigations. Assessment of beta-catenin shows aberrant nuclear pattern of staining in 70%-90% of desmoid tumors and 40% positivity in solitary fibrous tumor. CD34 is an important marker, positive in solitary fibrous tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Other additional markers are helpful in establishing mesencymal (Vimentin) or smooth muscle origin of the lesion (Desmin, smooth muscle actin).

CASE REPORT

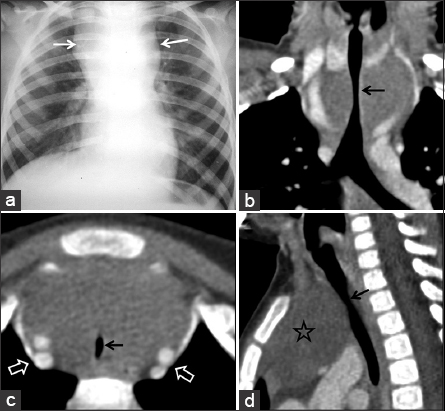

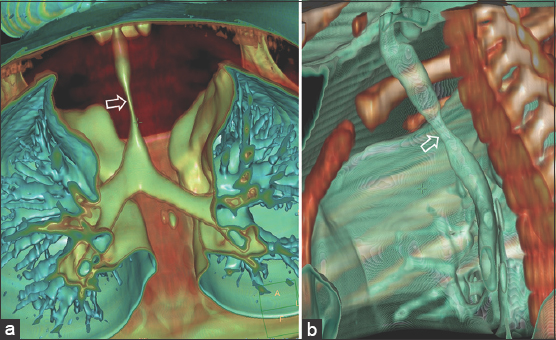

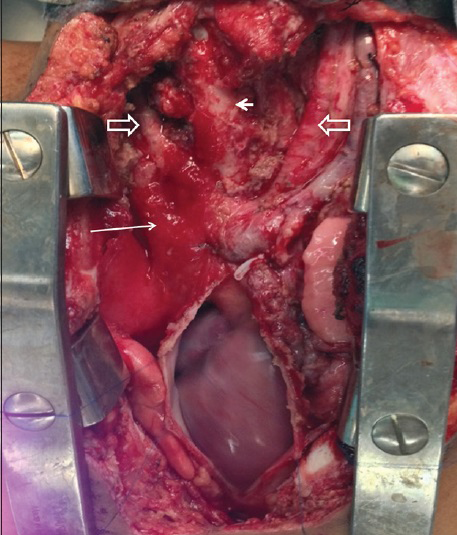

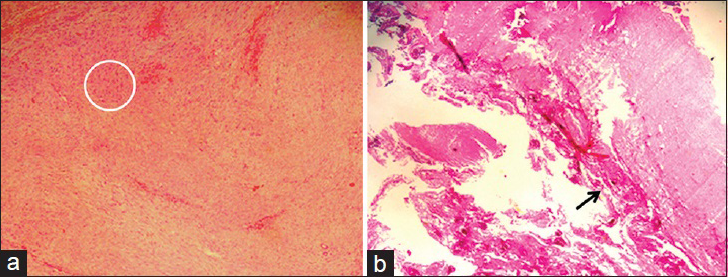

A three-year-old girl presented with a strider (noisy breathing) and exertional dyspnoea. The symptoms had started 4 months earlier and had progressively increased in severity. On examination, she was found to have enlarged veins in the neck. Chest radiograph showed wide superior mediastinum with a constriction at the level of cardiac pedicle [Figure 1a]. Chest radiograph indicated tracheal narrowing. MDCT evaluation confirmed the presence of a homogeneous, non-enhancing anterior mediastinal mass (MM) separating the mediastinal arteries, compressing and laterally displacing the superior vena cava [Figure 1b-d]. Trachea was narrow at the middle third [Figure 2a and b]. MRI examination was not performed due to financial constraints. A percutaneous trucut biopsy did not yield satisfactory tissue sample for analysis; Thoracoscopic biopsy was also unsuccessful due to the hard, densely adherent nature of the mass. Sternotomy revealed the mass to be adherent to the sternum, inseparable from the thymus and attached to the trachea. Tumor could not be separated from the trachea and mediastinal vessels due to dense adhesion and encasement. As the surgical team was unprepared for long complicated surgery, a planned second surgery was contemplated. Second surgery revealed an irregular hard mass on the left side of the sternum, adherent to the cervical trachea and pericardium, carotid sheath, and aortic arch. Both tracheo-esophageal grooves were infiltrated by the tumor. Patient underwent surgery and near-complete removal of the tumor was achieved [Figure 3]. Examination of the specimen revealed multiple firm, gray-white tissue fragments with a whorled cut surface and brownish tissue fragments of the thymus. Microscopy showed a hypocellular lesion composed of bland spindle cells with scanty pale amphophilic cytoplasm, in collagenous stroma [Figure 4]. The lesion had focally dense hypocellular, collagenous areas and a few largely thin-walled vessels. The tumor showed focal infiltration of the thymus. There was no indication of malignancy. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were diffusely positive for vimentin and smooth muscle actin (SMA) markers. The tumor cells were negative for pancytokeratin, high molecular weight cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), Desmin, S-100, cluster of differentiation markers- CD34, CD31, CD117 and estrogen receptor (ER). While positive vimentine and SMA indicated desmoid tumor, negative markers excluded lesions of other mesenchymal origin. Overall appearance was consistent with a desmoid type of infantile fibromatosis. The child had an uneventful recovery and a short asymptomatic period of 7 months. However, she presented again with airway symptoms, needing tracheostomy. She had developed breathing difficulty approximately 5 months after surgery. In view of the previous surgery, recurrent lesion with airway obstruction was considered. MD CT imaging demonstrated residual mass lesion in the mediastinum with persistent narrowing and distortion of the airway. She is on follow up with tracheostomy.

- 3-year-old female with noisy breathing and exertional dyspnoea with suspected mediastinal mass. (a) Plain radiograph shows mediastinal widening (white arrows) with relative narrowing at cardiac pedicle. (b) Coronal CT image shows tracheal narrowing by the homogeneous mass (black arrow). (c) Axial CT image demonstrates slit-like configuration of trachea (black arrow) due to compression. Blood vessels are widely separated (open arrows). (d) Sagittal CT image shows homogeneous anterior mediastinal mass (star) and relative narrowing of trachea (black arrow).

- 3-year-old female with noisy breathing and exertional dyspnoea with suspected mediastinal mass. (a and b) 3D rendered images show narrowing of the trachea (arrows).

- 3-year-old female with noisy breathing and exertional dyspnoea with suspected mediastinal mass. Surgical bed after resection of the mass reveals superior vena cava, innominate vein (long arrow), great arteries (open arrows) and trachea (short arrow).

- 3-year-old female with noisy breathing and exertional dyspnoea with suspected mediastinal mass. Histological examination of the specimen; Photomicrograph with the hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue (a) at magnification of ×100 shows hypocellular tumor (circle) consisting of bland spindle cells, (b) at magnification of ×20 shows tumor adherent to thymic tissue (black arrow).

DISCUSSION

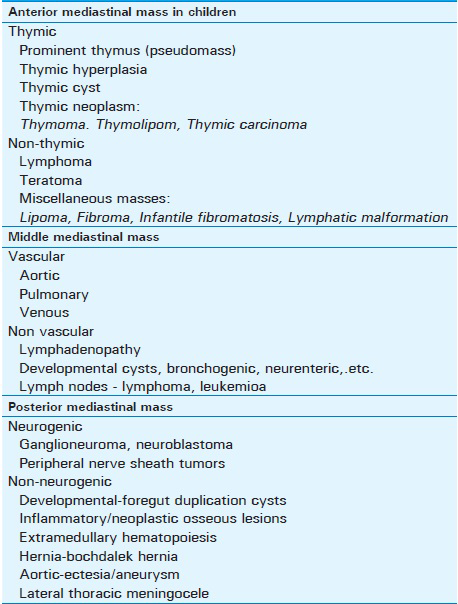

Mesenchymal tumors constitute less than 2% of all mediastinal tumors.[2] Fibromatosis is categorized as a mesenchymal tumor, grouped as either superficial or as deep fibromatosis. Deep fibromatosis is more common and has three subtypes; abdominal, intra-abdominal, and extra-abdominal types. These lesions are not known to metastasize.[2] The common sites of involvement in fibromatosis are the shoulder, thigh, arm, back, and buttocks. It is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis of a pediatric mediastinal mass. In our patient, based on clinical and imaging evidence indicating an anterior MM, lesions like germ cell tumor, lymphoma or a developmental lesion were considered in the differential diagnosis.[3] A list of mediastinal tumors in pediatric age group is presented in Table 1. Thymoma, not a common lesion of this age group, is relatively soft in consistency and rarely results in tracheal encasement. Common cause of anterior mediastinal mass in children includes germ cell tumor, thymic developmental cysts, lymphoma, leukemia and unusual mesenchymal tumors. The germ cell tumor and lymphatic or developmental cysts can be characterised by imaging with CT or MR. Fibromatosis of the mediastinum is not reported frequently. A few of the reported cases are located in the anterior mediastinum, related to sternum, in relation to the heart or in relation to the esophagus. All of them were noted in elderly patients, presenting as a non-specific, relatively homogeneous, non-enhancing focal mass lesions which on histological evaluation were shown to be a fibroma or fibromatosis.[1345] Authors did not come across MRI or PET description of a lesion in mediastinum.

Failure of attempted percutaneous and thorascopic biopsy due to the hard consistency of the lesion was perhaps the most important clue to nature of the lesion, further substantiated by adherence of the mass to sternum, trachea, and vascular structures. Described locations of mediastinal fibromatosis include the anterior mediastinum, peri-esophageal region, posterior mediastinum, the sternum, and adjacent to the heart. Encasement and obstruction of venous structure like superior vena cava are well described.[4] In the evaluation process, MRI can provide clues to the compact, fibrous nature of the mass which shows relatively low T1 and T2 signals. However, fibromatosis in other body locations demonstrate signal changes related to cellular versus fibrous components of the lesion, hence can vary depending on the phase of the lesion.[5] Studies have shown, fibromatosis in other body locations show varying signal intensity, depending on their histologic composition. It has been observed that greater the cellularity and lesser the amount of collagen, the higher is the T2-weighted signal intensity.[67] Generally, lesions are isointense to slightly hyperintense relative to skeletal muscle on T1-weighted images and intermediate between muscle and fat on T2- weighted images.[7]

A review of pathology studies indicates that these tumors have similar morphology and behaviour to that of the adult form of fibromatosis.[8] These tumors show diffuse nuclear beta-catenin expression, an indication of deep fibromatosis, which can aid in the diagnosis.[9] Important immuno-histochemical markers[10] for the diagnosis of fibromatosis and other soft tissue tumors are presented in Table 2. Complete surgical resection, is the treatment of choice, but this may not be often possible.[1] Radiation therapy is an effective treatment after incomplete resection.[10] Radiation therapy can be considered following incomplete surgery or for inoperable tumors. Local control rate of up to 93% is reported in primary therapy with improved disease control in adjuvant settings as well[1112] Total doses ranging from 36.0 to 76.2 Gy have been reported with doses higher than 50 Gy being associated with better local control.[13]

CONCLUSION

We present an unusual case of infantile fibromatosis of the anterior mediastinum in a child, emphasizing role of imaging and image guided biopsy. Infantile fibromatosis of the mediastinum should be considered in the differential diagnosis of any child presenting with a mediastinal mass.

Acknowlegements

Authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contribution of Dr. Ashley D’Cruz, MS, M Ch. Director of Pediatric Surgery Service and Dr. Varun Bhat in the preparation of this report.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2015/5/1/34/159452

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil

Conflict of interest: There are no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Enzinger and Weiss's Soft Tissue Tumors. (5th ed). Philadelphia: Mosby; 2008. p. :1109-1116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant pulmonary andmediastinaltumors inchildren: Differential diagnoses. Cancer Imaging. 2010;10:S35-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mediastinalfibromatosispresenting with superior vena cava syndrome. Respiration. 1999;66:464-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Juvenilefibromatosisof the posteriormediastinumwith intraspinal extension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:522-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging in fibromatosis: Results in 26 patients with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:539-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic resonance appearance of fibromatosis: A report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 1990;19:495-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nuclear beta-catenin expression distinguishes deep fibromatosis from other benign and malignant fibroblastic and myofibroblastic lesions. Am J SurgPathol. 2005;29:653-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. (6th ed). Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2015. p. :867-930.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of radiation therapy in the management of desmoids tumors. StrahlentherOnkol. 2002;178:78-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fibromatosis: Benign by name but not necessarily by nature. ClinOncol (R CollRadiol). 2007;19:319-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgery versus radiation therapy for patients with aggressivefibromatosis or desmoidtumors: A comparative review of 22 articles. Cancer. 2000;88:1517-23.

- [Google Scholar]