Translate this page into:

MRI of Uncommon Lesions of the Large Bowel: A Pictorial Essay

Address for correspondence: Dr. Christine U Lee, Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic, 200 Frist Street SW, Rochester - 55905, Minnesota, USA. E-mail: lee.christine@mayo.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

This pictorial essay briefly discusses methods for optimizing bowel imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and illustrates the MRI appearance of a variety of unusual lesions involving or related specifically to the large bowel.

Keywords

Imaging

large bowel

magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Imaging of the large bowel has traditionally relied on fluoroscopic techniques; however, cross-sectional modalities including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography, and positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) have become commonplace since the mid 1990s. Depending on the indication and area of interest, advantages of each of these modalities vary. MRI, for example, has found clinical utility in staging of rectal carcinoma,[12] with clear advantages over endoscopic, sonographic, or clinical staging. Increasing use of MR enterography (MRE) for evaluating inflammatory bowel disease, while primarily being performed for detection and characterization of small bowel disease, also allows assessment of the colon. Dedicated MR colonography remains a rare application, most often performed in research settings as an alternative to screening CT colonography. MRI allows superior soft tissue characterization in comparison to CT and ultrasonography, and does not require ionizing radiation.

MRI for inflammatory bowel disease and rectal cancer staging represents some of the most rapidly growing segments of our body MRI practice, and the increasing volumes (and increasing scrutiny of bowel) have led to the detection of several unusual lesions involving the lower gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This pictorial essay briefly discusses methods for optimizing bowel imaging with MRI and illustrates the MRI appearance of a variety of unusual lesions involving or related specifically to the large bowel.

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

MRE protocols are primarily designed to optimize assessment of small bowel in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease; fortunately, these protocols frequently improve visualization of the large bowel as well. Effective MRE examinations require adequate distention of bowel, achieved by ingestion of an oral contrast agent (VoLumen®), reduction of peristalsis via intravenous and/or subcutaneous injection of an antiperistaltic agent (glucagon), and time-efficient protocols, typically incorporating fast T2-weighted sequences such as balanced steady-state free precession (b-SSFP) and single-shot fast spin echo (SSFSE), and dynamic gadolinium-enhanced 3D spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) acquisitions in coronal and axial planes.

Rectal cancer staging generally requires high spatial resolution 2D fast spin echo (FSE) images[2] in three planes for adequate tumor delineation and staging. Distention of the rectum with ultrasound gel aids in visualization of the primary tumor, and is generally less useful in staging extramural tumor extension. Three small field of view (FOV), high spatial resolution FSE acquisitions can be fairly time consuming, and are not infrequently degraded by artifact; these artifacts are usually related to motion from peristalsis or patient movement. We find that addition of shorter acquisitions (such as post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images and 2D SSFSE and/or b-SSFP images) can be very helpful in cases where the FSE images are significantly degraded by artifact.

Lesions involving bowel may occasionally be serendipitously detected on MRI not dedicated to bowel imaging. In these cases, additional SSFSE and/or b-SSFP acquisitions in planes oriented parallel and perpendicular to the mass or to the associated bowel loop may be helpful in providing motion-free images of the lesion. Diffusion-weighted images may also be useful – these should generally be obtained with a relatively high b-value (>800 s/mm2), so the T2 shine-through effects from fluid within the bowel lumen are reduced.

CASES

Cecum/appendix

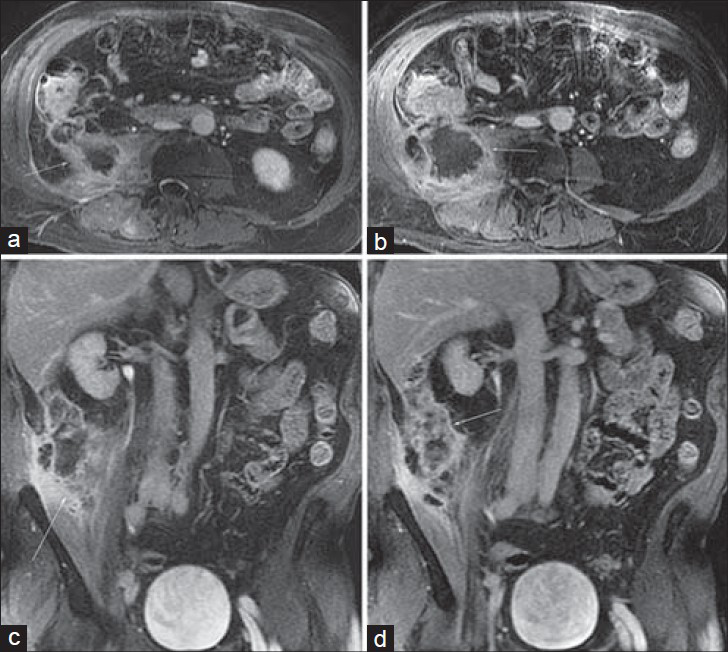

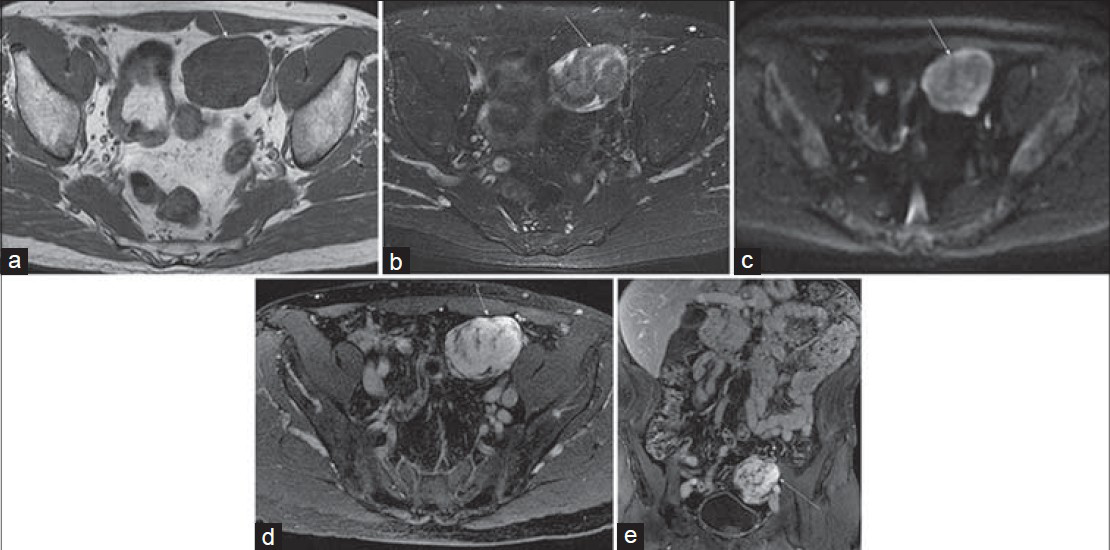

Primary appendiceal adenocarcinoma [Figure 1] is rare in comparison to colorectal adenocarcinoma, and constitutes less than 0.5% of all neoplasms of the GI tract. It is, however, the most common appendiceal cancer. Primary appendiceal tumors are rarely diagnosed preoperatively and are found in < 2% of appendectomy specimens.[3] Primary appendiceal adenocarcinomas usually arise in pre-existing adenomas and exhibit either a cystic or colonic growth pattern. The cystic type is a mucin-producing tumor. These tumors have a tendency to rupture and spread throughout the peritoneal cavity, resulting in pseudomyxoma peritonei. Colonic type lesions (the diagnosis in this case) develop from a tubular or tubulovillous adenoma, and are comparable to colonic adenocarcinomas.[3]

- Primary appendiceal adenocarcinoma in a 67-year-old man with night sweats and weight loss. Post-gadolinium (a) and (b) axial and (c) and (d) coronal 3D SPGR images from an MR urogram demonstrate an enlarged appendix (arrow) associated with central necrosis, mural thickening, and enhancement that extends into the peritoneal walls and invades the adjacent psoas muscle. Note the pericecal soft tissue enhancement as well as mural enhancement of the cecum itself.

Appendiceal adenocarcinoma appears as an appendiceal mass on MRI, and in this case is accompanied by extensive central necrosis and local invasion of the psoas muscle. Carcinoid tumors comprise 2% of all gastrointestinal (GI) tumors and are characterized by their slow growth, neuroendocrine origin, and association with carcinoid syndrome. Most carcinoid tumors arise in the distal ileum within 2 feet of the ileocecal valve (a proclivity shared with Meckel's diverticulum) and some authors have found the appendix to be a relatively common site of origin.[45] Most appendiceal carcinoids are serotonin-producing enterochromaffin cell tumors, making them more similar to jejunal and ileal carcinoids than to colonic carcinoids. MRI features of carcinoid tumors of the GI tract are nonspecific and can include heterogeneous, predominantly hypointense T1 signal, hyperintense T2 signal, and a heterogeneously enhancing, well-defined nodular mass or regional, relatively uniform segmental mural thickening of the bowel. Early imaging features of appendiceal carcinoid can mimic inflammatory disease. Clinical history including cutaneous flushing, diarrhea, vague intermittent abdominal pain, and elevated urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) and serum chromogranin A levels may help in distinguishing carcinoid from other neoplastic and inflammatory diseases, and the diagnosis and extent can be confirmed with Indium (111In)-octreotide scintigraphy and more recently with 11C-5-hydroxytryptophan (11C-5-HTP) PET.[6] Figure 2 shows an appendiceal carcinoid tumor with a well-defined nodular hyperenhancing mass on MRI.

- Appendiceal carcinoid detected as an incidental mass on CT of a 61-year-old woman; MRI was performed for further characterization. (a) Axial pre-gadolinium T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted images demonstrate a circumscribed, exophytic, nodular mass (arrow) arising from the cecum and possibly from the appendix as the appendix is not seen elsewhere. (c) and (d) Post-gadolinium coronal 3D SPGR images demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement of this mass.

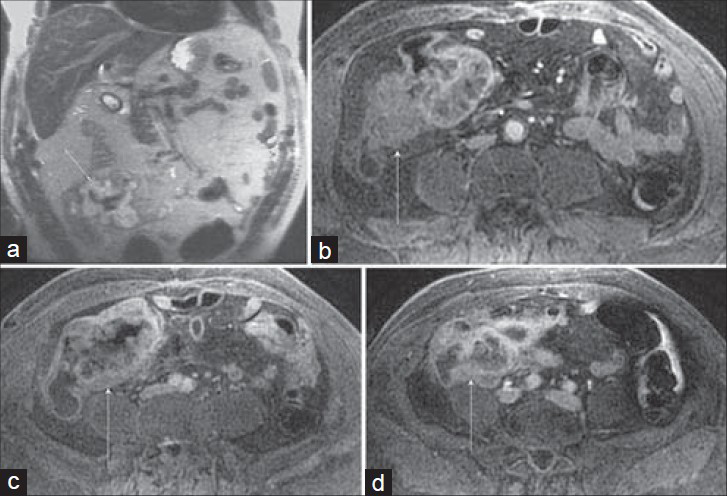

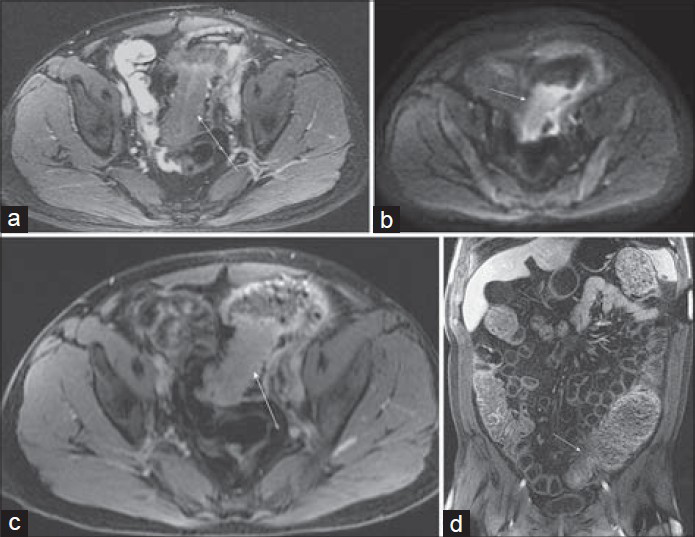

Cecal carcinoma can have a variety of presentations, and not infrequently, as in this case, may be entirely asymptomatic and detected incidentally [Figure 3]. The survival rate of cecal carcinoma compared to other colon cancers has been deliberated for decades[7] with earlier reports describing a poorer prognosis that was thought to result from its tendency to present with vague, chronic symptoms, including pain, weight loss, and anemia, as well as its anatomy and physiology. However, subsequent investigations could not substantiate this and either found similar or higher[8] survival rates for cecal carcinoma, suggesting that prognosis is best predicted by clinicopathologic staging.[7]

- Cecal carcinoma incidentally discovered on MRI performed to evaluate a suspected post-cholecystectomy common hepatic duct injury in a 66-year-old man. (a) Coronal SSFSE and (b–d) three axial post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images demonstrate a nodular enhancing cecal mass (arrow) that involves the ileocecal valve. Several enlarged mesenteric pericecal nodes were negative for metastatic involvement at pathology. Note the paucity of signal inferiorly on the SSFSE image (a) which is a result of selecting the upper coil elements for an abdominal examination. There is improved signal-to-noise ratio for the 3D SPGR images (b–d) which had the appropriate coil selected.

The heterogeneously hypoenhancing mural mass shown in Figure 3 is a fairly typical appearance, and the high signal intensity seen on the SSFSE image likely reflects the substantial mucinous componentof the tumor.

Ascending colon

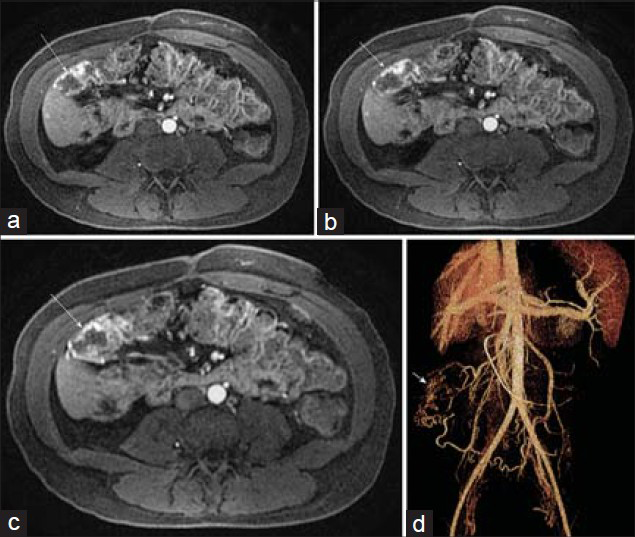

Angiodysplasias of the GI tract [Figure 4] are characterized by vascular abnormalities of the submucosal and mucosal layers and include hemangiomas, arteriovenous malformations, and angiosarcomas. Most lesions are found in the cecum and ascending colon of patients older than 60 years of age. The most common signs and symptoms when present are associated with GI bleeding, which can be recurrent or chronic.

- Arteriovenous malformation in the ascending colon in a 28-year-old woman with lower GI bleeding and chronic pancreatitis. (a–c) Post-gadolinium axial 3D SPGR images demonstrate serpiginous early arterial phase mural enhancement of a segment of the ascending colon (arrow). (d) Volume rendering from CT angiogram illustrates the malformation just inferior to the hepatic flexure with a feeding artery from the inferior mesenteric artery and a draining right colic vein.

Endoscopic imaging is currently the main tool for diagnosis in the upper and lower GI tract, while capsule endoscopy is often used for the small bowel.[910] MR or CT angiography, or catheter-based angiography is often used to confirm the location of suspected bleeding or to further evaluate for a primary diagnosis. While arterial phase images from a standard dynamic contrast-enhanced 3D SPGR acquisition [as shown in Figure 4] are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis, if a vascular lesion is suspected, MR angiographic acquisitions using an intravascular gadolinium contrast agent might improve the sensitivity for detection of subtle lesions.

Transverse colon

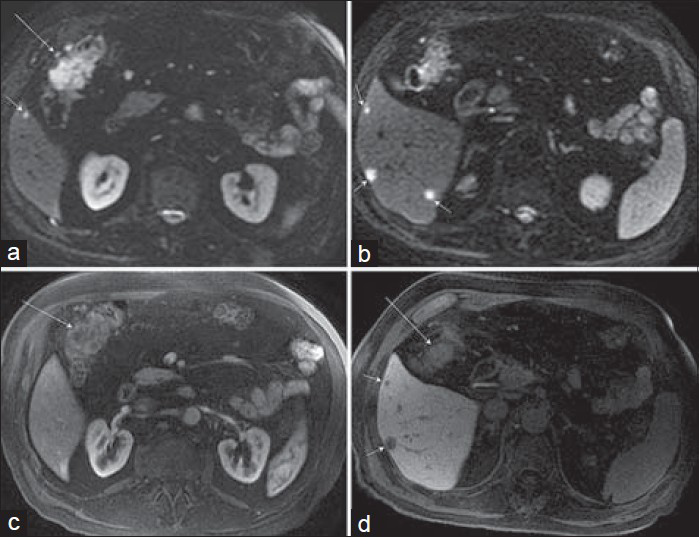

Hepatic flexure adenocarcinoma [Figure 5] is considered a cancer of the right-sided colon, which anatomically includes the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon. Some studies have investigated the histopathologic expression of colorectal cancer depending on tumor location and observed that right-sided colon cancers tended to be bulky, polypoid, and exophytic while left-sided cancers tended to be infiltrative, circumferential, and associated with luminal narrowing.[111213] Colon cancers located in the hepatic flexure, splenic flexure, or transverse colon can often be included in the FOV of standard abdominal examinations performed to screen for hepatic metastases, and small modifications of standard protocols may provide additional information regarding nodal or peritoneal disease, vascular invasion, and local tumor extension.

- Hepatic flexure adenocarcinoma in a 74-year-old man that was discovered on routine colonoscopy. MRI was requested to screen for hepatic metastases, and a hepatobiliary contrast agent, gadoxetate disodium (Eovist), was used. a and b) Axial diffusion-weighted images (b = 800 s/mm2) demonstrate not only increased signal corresponding to a hepatic flexure mass (a, long arrow), but also multiple small hepatic metastases (short arrows) in the inferior right lobe. (c) Axial post-gadolinium arterial phase image demonstrates minimal enhancement of the colonic mass. (d) Hepatobiliary phase post-gadolinium axial image shows hypoenhancing hepatic metastases (short arrows) and partially visualized ill-defined hepatic flexure lesion (long arrow).

Descending colon

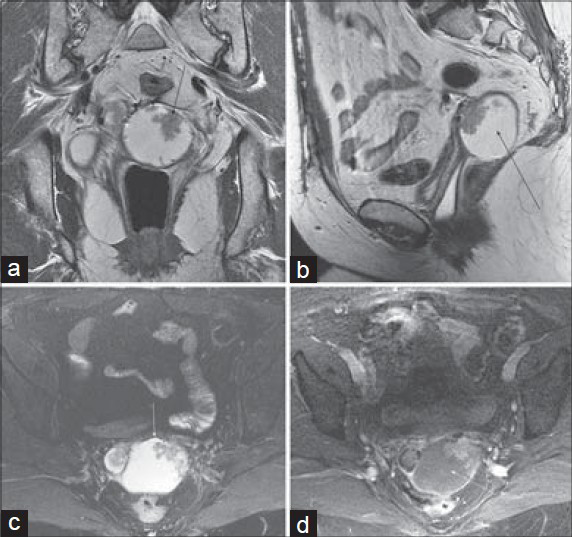

Lipomas [Figure 6] are the most common benign mesenchymal tumor of the colon with a frequency as high as 6% in clinical and autopsy series.[1415] These tumors comprise well-differentiated fatty tissue surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule which lends itself to a sharply circumscribed morphology on cross-sectional imaging. Lipomas occur more frequently in the right colon and are most common near the ileocecal valve, and this case is presented in this section due to its uncommon location. Patients are generally asymptomatic, particularly when the tumors are relatively small, but lesions larger than 3–4 cm in diameter may cause intussusception or obstruction and patients can present with abdominal pain or discomfort, bleeding per rectum, or a change in bowel habits.

- Giant descending colonic lipoma in a 52-year-old woman with previously resected renal cell carcinoma. (a) Axial T1-weighted and (b) fat-suppressed T2-weighted FSE images demonstrate a luminal mass (arrow) in the descending colon with signal intensity identical to adjacent mesenteric fat. (c) Coronal SSFSE image demonstrates a high signal intensity lesion (arrow) in the descending colon without proximal obstruction. Incidentally noted are a small hepatic hemangioma and a left renal cyst.

The diagnosis of lipoma is made by demonstrating that the lesion follows the signal intensity of mesenteric or subcutaneous fat on acquisitions performed without and with fat suppression – typically SSFSE and/or b-SSFP images in an MRE examination, or alternatively by examination of fat and water images from a Dixon 3D SPGR acquisition.

Sigmoid colon

Mesenchymal lesions of the GI tract include gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), lipomas, desmoid tumors, schwannomas, and true smooth muscle neoplasms. True smooth muscle neoplasms of the GI tract, such as leiomyomas [Figure 7] and leiomyosarcomas, show smooth muscle differentiation by light microscopy and lack CD117 (KIT mutations), in contrast to GISTs.

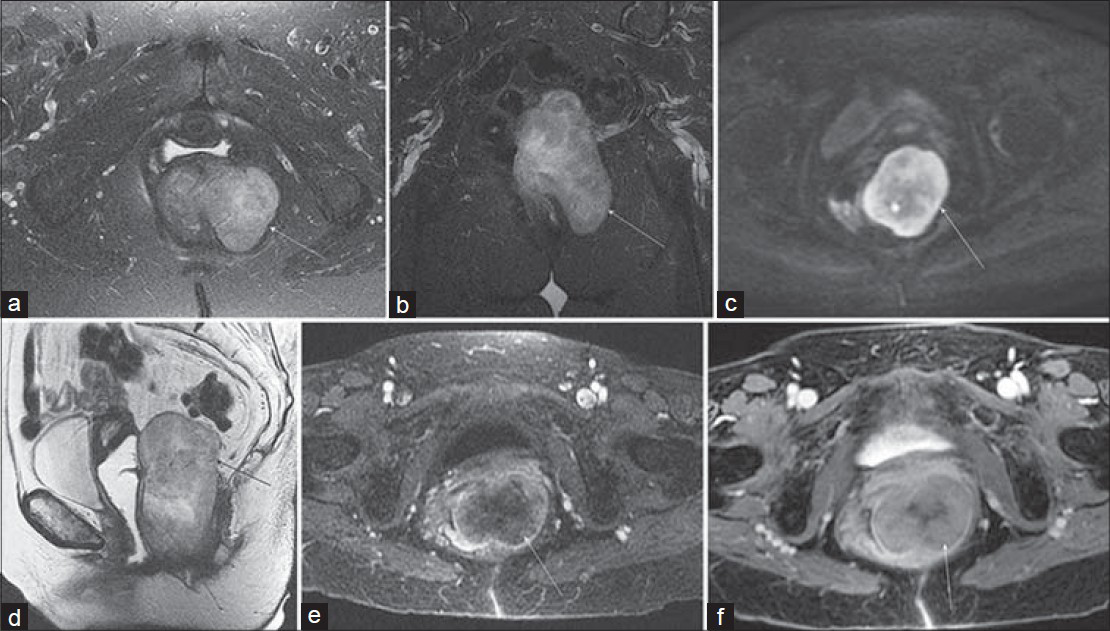

- Sigmoid leiomyoma in a 65-year-old man with intermittent left lower quadrant pain that was thought to be due to urolithiasis. CT showed a pelvic mass and pelvic MRI was performed for further characterization. Axial (a) T1-weighted and (b) T2-weighted images show a well-circumscribed mass (arrow) with diffuse low T1 signal intensity and a whorled appearance on the T2-weighted image with central hypointensity. (c) Diffusion-weighted image (b = 800 s/mm2) (c, arrow) also demonstrates central low signal intensity with a hyperintense rim. Post-gadolinium 3D SPGR (d) axial and (e) coronal images show avid enhancement of the lesion.

In the GI tract, polypoid leiomyomas are more common than intramural leiomyomas and in one review of 85 cases,[16] the polypoid form involved largely the colorectum (with the sigmoid colon and rectum being more frequent) and the intramural form involved the esophagus, stomach, and ileum. Polypoid leiomyomas manifest as small sessile polyps, while intramural leiomyomas form well-circumscribed lobulated masses arising from the muscularis propria and bulging into the mucosa or serosa. MRI features [Figure 7] include a mildly heterogeneous appearance, frequently with low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and significant enhancement following gadolinium administration.

Diverticulitis can be diagnostically challenging both clinically where gynecologic abnormalities can be confounding and radiologically [Figure 8] where imaging differential diagnoses include colon cancer and ischemia.[17]

- Diverticulitis with organizing mural abscess on MR enterography of a 40-year-old man with left lower quadrant pain radiating to the umbilicus and back. (a) Axial fat-suppressed 2D b-SSFP, (b) diffusion-weighted b = 600 s/mm2, and (c) post-gadolinium 3D SPGR axial and (d) coronal images demonstrate persistent segmental mural thickening and luminal narrowing (apple core lesion) of the sigmoid colon with diffuse restricted diffusion and mild mural enhancement (arrow). There is associated obstruction with dilation of the sigmoid colon proximal to the lesion. This was described as highly suspicious for malignancy. Endoscopic biopsy was negative for malignancy; however, conservative clinical management was unsuccessful and surgery was recommended given his persistent symptoms and obstruction.

CT is the imaging modality of choice for evaluation of suspected diverticulitis. CT and MRI features that are associated with, but not exclusive to diverticulitis include soft tissue stranding suggesting inflammation, bowel wall thickening, mural enhancement, abscess formation, and localized or diffuse pneumoperitoneum. The high sensitivity of CT (and likely MRI) for detection of diverticulitis is not matched by a corresponding high specificity, as emphasized in Figure 8, which was interpreted as suspicious for carcinoma; therefore, it is important to document resolution of disease and exclude an underlying malignancy.

The rectosigmoid colon is the most common site of bowel involvement by metastatic or recurrent ovarian carcinoma [Figure 9], and can occur from direct extension or peritoneal seeding. Metastases from ovarian cancer usually invade the bowel serosa, resulting in characteristic tethering and kinking, and may ultimately cause obstruction. MRI can often demonstrate an eccentric mass, and the diagnosis is usually straightforward in a patient with a history of ovarian carcinoma.

- Ovarian cancer metastasis involving the sigmoid colon and vagina in a 56-year-old woman with a history of ovarian cancer. T2-weighted images without fat suppression in the (a) coronal and (b) sagittal planes and (c) fat-saturated T2-weighted image demonstrate a mixed solid cystic mass (arrow) in the pouch of Douglas just anterior to the sigmoid colon, with spiculation and tethering of the anterior margin of the sigmoid. (d) Axial post-gadolinium 3D SPGR image shows enhancement of the mural nodule within the metastasis, as well as stranding and tethering of the adjacent sigmoid colon.

Rectum

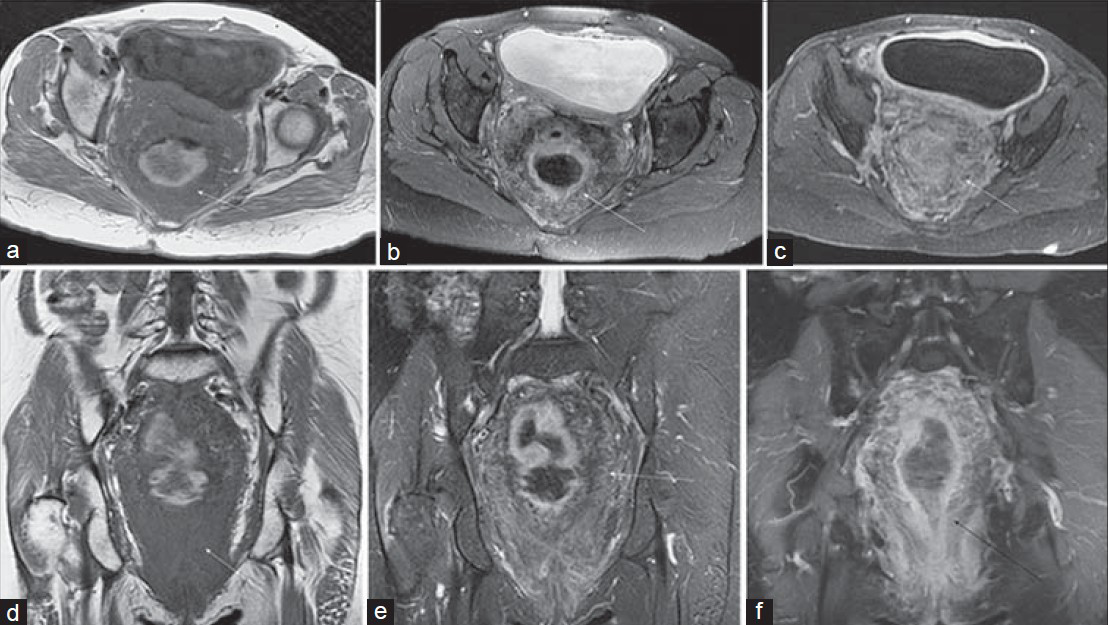

Plexiform neurofibromas are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that comprise a complex network (plexiform) of peripheral nerves arranged in a tortuous configuration. These tumors are pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis I (NF1) and are found in about 30% of NF1 cases. Plexiform neurofibromas are usually congenital or appear in childhood, and often have rapid enlargement during adolescence. They may persist for years without causing significant symptoms; however, when they do cause neurologic deficits, medical or surgical treatment is difficult.

While neurofibromas classically exhibit high signal intensity on T2-weighted images and moderate enhancement following gadolinium administration, plexiform lesions, particularly those involving very small nerves, may show only mild increased T2 signal intensity and enhancement, and often, as in this case, the most striking appearance is seen on T1-weighted images [Figure 10]. Diagnosis is often aided by identification of multiple subcutaneous neurofibromas (if the history of NF1 is not known or has not been provided).

- Perirectal plexiform neurofibroma in a 55-year-old woman with a history of pelvic radiotherapy for endometrial cancer and now presenting with fecal incontinence. (a) Axial T1-weighted, (b) T2-weighted, and (c) post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images show extensive non-obstructive soft tissue (arrow) surrounding the rectosigmoid colon. (d) Coronal T1-weighted, (e) T2-weighted, and (f) post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images again demonstrate the markedly decreased T1 signal intensity, as well as mildly increased T2 signal intensity and mild enhancement associated with the plexiform neurofibroma.

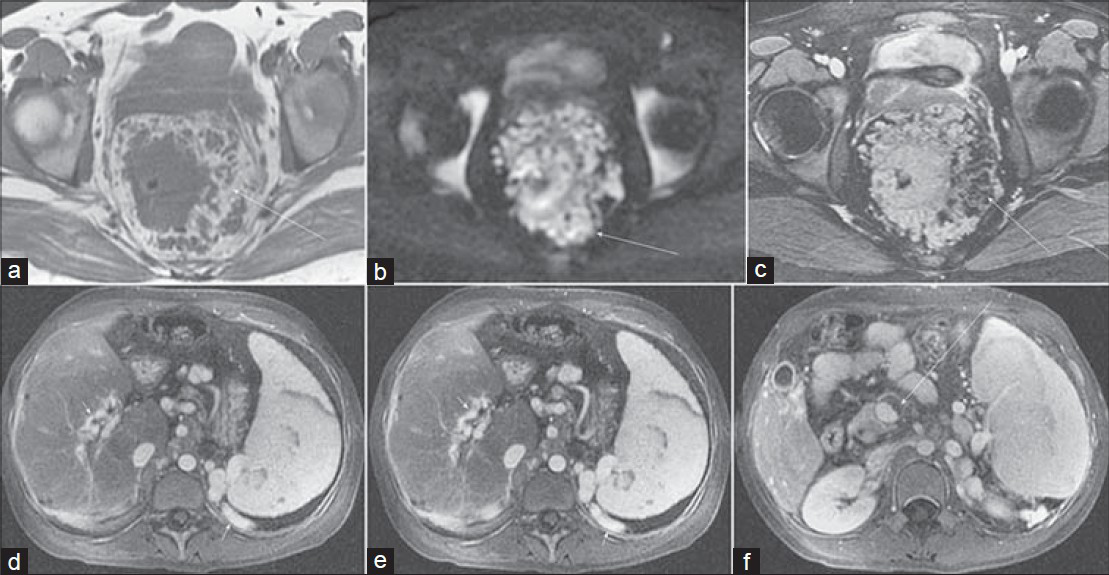

Mesenchymal tumors of the GI tract were generally classified as leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas until the 1980s when it was discovered that a number of these lesions lacked features of smooth muscle and expressed antigens related to neural crest cells. More specifically, GISTs [Figure 11] are defined as spindle cell, epithelioid, pleomorphic mesenchymal tumors that express the Kit protein (this is a stem cell factor receptor protein), and activation of the receptor leads to unchecked cell growth and resistance to apoptosis.

- Rectal GIST in a 79-year-old woman with constipation and a palpable mass on rectal examination. Axial (a) fat-saturated T2-weighted and (b) diffusionweighted (b = 800 s/mm2) images demonstrate an exophytic mass (arrow) involving the left lateral wall of the rectum with mildly heterogeneous increased signal intensity. (c) Coronal fat-suppressed and (d) sagittal non–fat-saturated T2-weighted images again show the exophytic mass extending from the lateral rectal wall and abutting the posterior margin of the vagina. Axial (e) arterial phase and (f) delayed post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images reveal gradual internal enhancement of the lesion.

GISTs are relatively rare tumors, accounting for 1–3% of all GI neoplasms, with approximately 2000 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States. The peak age of incidence is 50–60 years, with a slight male predominance. Most tumors arise in the stomach (60–70%) or small intestine (20–30%), with the lesions found less frequently in the esophagus, mesentery, colon, or rectum. Approximately 20–30% of the lesions are malignant, with the liver and peritoneal cavity being the most common sites of metastases.

The appearance on MRI has not been well documented in the literature. In general, larger lesions tend to exhibit heterogeneous enhancement which persists on venous and equilibrium phase images and multiple regions of cystic degeneration or necrosis with high T2 signal intensity, while smaller lesions may have a more uniform appearance. Lesion growth can be exophytic or intraluminal, and exophytic lesions are often quite large by the time they become symptomatic.

Rectal varices [Figure 12] represent a portal–systemic collateral pathway that usually develops in the setting of portal hypertension or obstructed portal venous flow. The rectum is a site of overlapping portal and systemic venous drainage: Superior hemorrhoidal veins of the inferior mesenteric system and the middle and inferior hemorrhoidal veins of the iliac system.

- Rectal varices in a 29-year-old woman with hematochezia. Axial (a) T1-weighted, (b) diffusion-weighted (b = 600 s/mm2), and (c) fat-suppressed 2D b-SSFP images demonstrate diffuse nodular thickening of the rectum with surrounding serpiginous structures. (d–f) Axial portal venous phase post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images in the abdomen reveal chronic occlusion of the portal vein (arrow) with cavernous transformation (short arrow), splenomegaly, and perisplenic varices (short arrow).

Rectal varices consist of small venous collateral vessels within the rectal wall and in the perirectal region. The appearance can become somewhat mass-like, as seen in Figure 12, and a circumferential rectal hemangioma can have a very similar appearance. The highly vascular nature of the lesion is generally apparent, however, and should not be mistaken for a rectal carcinoma.

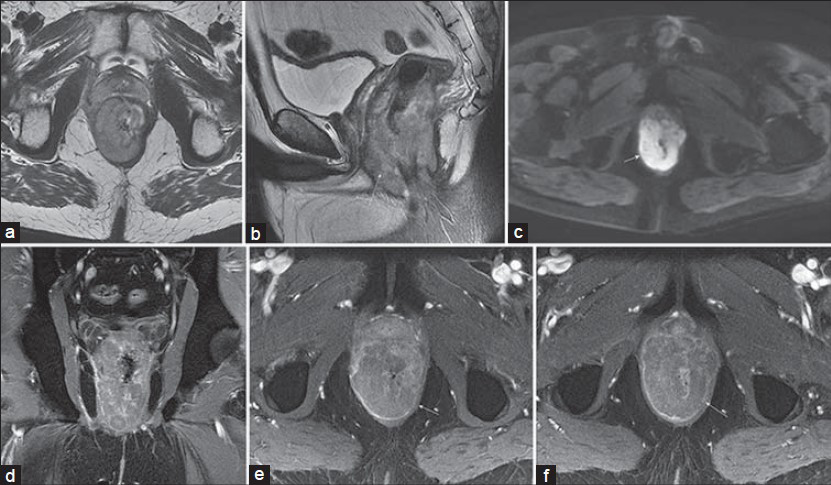

Small cell carcinoma (SCC) affecting the colon and rectum [Figure 13] is rare, accounting for approximately 0.2% of all colorectal cancers. Three subtypes have been described: Undifferentiated SCC, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and stem cell carcinoma. Histologic diagnosis is confirmed by documenting the presence of at least two of three immunohistochemical markers, the most common of which is synaptophysin.

- Rectal small cell carcinoma in a 69-year-old man with crampy abdominal pain. (a) Sagittal and (b and c) axial T2-weighted images with endorectal coil placement demonstrate a large heterogeneous circumferential rectal mass (arrow). Post-gadolinium 2D SPGR images in the (d) coronal and (e and f) axial planes show a large heterogeneously hypoenhancing mural mass invading the presacral space and abutting the prostate anteriorly.

The rectum is the most common location for SCC, followed by the cecum and sigmoid. As is true of SCC in other locations, rectal lesions tend to show aggressive behavior. Most patients (70–80%) have liver or nodal metastases at diagnosis, and the prognosis is generally poor, with 6-month survival of 58% and 5-year survival of approximately 6%.

The appearance of rectal SCC has not been well described in the MR literature; however, the large, diffusely infiltrative lesion illustrated in this case is likely a fairly typical example. While it is probably unrealistic to arrive at a specific diagnosis, the appearance might suggest a differential diagnosis including an unusually aggressive rectal carcinoma as well as lymphoma and metastasis.

Primary rectal lymphoma [Figure 14] is rare, representing 0.1–0.4% of primary rectal tumors.[181920] Although the GI tract is a common site of extranodal lymphoma, colorectal involvement is relatively infrequent (6–20% of GI lymphomas) and is associated with a worse prognosis.[2122] B-cell and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas are the most common colorectal lymphomas.

- Rectal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in a 42-year-old man with recent weight loss and change in bowel habits. T2-weighted (a) sagittal and (b and c) axial images, as well as diffusion-weighted (b = 600 s/mm2) images demonstrate a slightly asymmetric circumferential mass (arrow) with mildly heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images and diffuse hyperintensity on the diffusion-weighted image. (d) Coronal and (e and f) axial post-gadolinium 3D SPGR images show mildly heterogeneous hypoenhancement of the mass.

Imaging findings are nonspecific and can overlap with rectal adenocarcinomas. One feature that may help to distinguish lymphoma from adenocarcinoma is the absence of proximal bowel obstruction that is often associated with adenocarcinomas of similar size. Extensive regional lymphadenopathy is often seen with secondary rectal lymphoma. MRI demonstrates a mural or, less frequently, a polypoid mass which typically has a mildly heterogeneous appearance and intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images, high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted images, and mild enhancement following gadolinium administration.

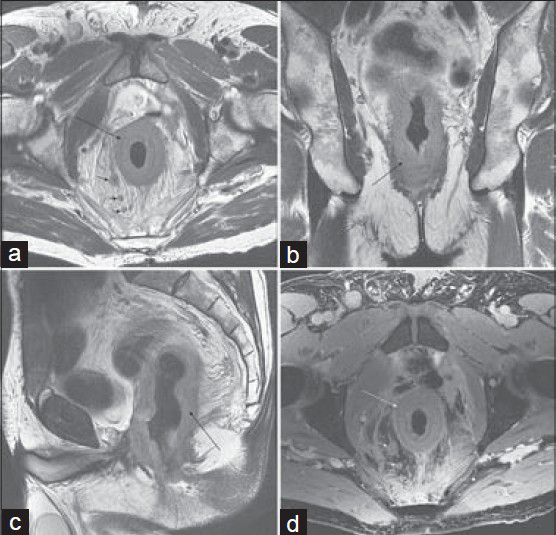

Figure 15 shows an unusual presentation of metastatic disease involving the rectum. Metastases to the intestine are relatively uncommon, more frequently involve small bowel, and generally present as focal submucosal masses. Rectal metastases have been reported from primary tumors including prostate, bladder, breast, ovarian, lung, and gastric cancer, as well as melanoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

- Metastatic involvement of rectum on MRI of the pelvis in a 73-year-old man with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder status post cytoprostatectomy. T2-weighted images in the (a) axial, (b) coronal, and (c) sagittal planes show diffuse circumferential soft tissue thickening of the rectum (arrow), as well as enlarged perirectal lymph nodes (short arrows). (d) Axial post-gadolinium 3D SPGR image (d) shows mild enhancement of the rectal wall.

Diffuse annular involvement of the rectum is an unusual presentation for metastatic disease, but has been described in patients with primary bladder urothelial cell carcinoma. The absence of the bladder and prostate (with susceptibility artifact from surgical clips visible on the post-gadolinium images) is also a clue to the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis includes primary rectal adenocarcinoma, and the long annular lesion could also be seen with lymphoma.

Anus

Anal mucinous adenocarcinoma [Figure 16] is a rare malignancy accounting for about 3% of anal cancers.[2324] Squamous cell carcinoma is similarly rare, but is strongly associated with the human papillomavirus. Presentation of anal cancer is variable, but generally includes anal pain, bleeding, or itching. Cross-sectional imaging is usually performed for evaluating for regional extent of the disease.

- Anal mucinous adenocarcinoma in a 61-year-old woman with hematochezia, fatigue, and weight loss, and a palpable anal mass. (a) Axial and (b) sagittal T2-weighted images demonstrate an exophytic hyperintense mass (arrow) extending anteriorly from the anal wall abutting the posterior margin of the vulva and invading the left levator muscle. (c) Diffusion-weighted image (b = 800 s/mm2) shows uniform hyperintensity within the mass. (d) Axial postgadolinium 3D SPGR image shows heterogeneous hypoenhancement of the mass with mild enhancement of the rim and internal septations. A rectal tube is in place.

CONCLUSIONS

This pictorial essay illustrates the appearance of a variety of unusual large bowel pathologies on MRI. While several of the above cases were imaged using dedicated enterography or rectal protocols, many others were discovered serendipitously during abdominal or pelvic examinations performed for different indications. Optimal MRI of large bowel lesions includes luminal distention, administration of antiperistaltic agents, and the use of rapid imaging techniques including SSFSE and b-SSFP acquisitions. Even when dedicated protocols are not performed, however, adequate characterization of incidental large bowel lesions is often possible, particularly if additional sequences can be performed before the patient is dismissed.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2014/4/1/71/148265

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- Preoperative assessment of prognostic factors in rectal cancer using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Br J Surg. 2003;90:355-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rectal carcinoma: Thin-section MR imaging for staging in 28 patients. Radiology. 1999;211:215-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary appendiceal carcinoma--epidemiology, surgery and survival: Results of a German multi-center study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:763-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoid tumor of the appendix: A consecutive series from 1237 appendectomies. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6699-701.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoid tumors: Imaging procedures and interventional radiology. World J Surg. 1996;20:147-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Midgut neuroendocrine tumors: Imaging assessment for surgical resection. Radiographics. 2014;34:413-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carcinoma of the colon and rectum: The natural history reviewed in 1704 patients. Cancer. 1982;49:1131-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arteriovenous malformation in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1977;185:116-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review article: Gastrointestinal angiodysplasia-pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:15-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of 17,641 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer: Differences in epidemiology, perioperative course, histology, and survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:57-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is there a difference in survival between right- versus left-sided colon cancers? Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2388-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of tumor location on the histopathologic expression of colorectal cancer. J BUON. 2006;11:317-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computed tomographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings of asymptomatic intra-abdominal gastrointestinal system lipomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2008;32:841-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Colonic lipomas: Outcome of endoscopic removal. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:435-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- True smooth muscle neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract: Morphological spectrum and classification in a series of 85 cases from a single institute. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:75-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- How to diagnose acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis: Proposal for a clinical scoring system. Ann Surg. 2011;253:940-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benign and malignant tumors of the rectum and perirectal region. Abdom Imaging. 2014;39:824-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- A solitary rectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep 2010 2010:bcr0120102649.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rare location of primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the rectum. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2013;52:508-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary colorectal lymphoma-A single centre experience. Surgeon (14):S1479-666X. Epub ahead of print

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary colorectal lymphomas: Review of the literature. Surg Oncol. 2007;16(Suppl 1):S169-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary anal mucinous adenocarcinoma: A case series. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2011;12:48-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancers of the anal canal: Diagnosis, treatment and future strategies. Future Oncol. 2014;10:1427-41.

- [Google Scholar]