Translate this page into:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Appearance of Schwannomas from Head to Toe: A Pictorial Review

Address for correspondence: Dr. Jamie Crist, 200 1st St. Sw, Rochester, MN 55905, USA. E-mail: crist.jamie@mayo.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Schwannomas are benign soft-tissue tumors that arise from peripheral nerve sheaths throughout the body and are commonly encountered in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2. The vast majority of schwannomas are benign, with rare cases of malignant transformation reported. In this pictorial review, we discuss the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) appearance of schwannomas by demonstrating a collection of tumors from different parts of the body that exhibit similar MRI characteristics. We review strategies to distinguish schwannomas from malignant soft-tissue tumors while exploring the anatomic and histologic origins of these tumors to discuss how this correlates with their imaging findings. Familiarity with the MRI appearance of schwannomas can help aid in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses, especially in unexpected locations.

Keywords

Magnetic resonance imaging

malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

peripheral nerve sheath tumor

schwannoma

INTRODUCTION

Schwannomas, sometimes referred to as neurilemmomas, are benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors that occur anywhere in the body and represent approximately 5% of all soft-tissue tumors. While the majority of cases occur sporadically, cases may be seen in association with genetic disorders such as neurofibromatosis (NF) Type 2 or, more rarely, Type 1. Schwannomas are composed of Schwann cells that normally produce myelin sheath covering the peripheral nerve. Schwannomas are further classified into two types based on distinct histological patterns – Antoni A and B types. Type 1 is highly cellular and demonstrates nuclear palisading and Verocay bodies. Verocay bodies refer to a stacked arrangement of two rows of elongated palisading nuclei and alternating bands of acellular zones that are made up of tubular cytoplasmic processes of Schwann cells. Type 2 has more loosely organized cellular structure with areas of myxomatous and cystic changes. It is often thought that Type 2 represents degenerated Type 1 tissue. The tumors develop as fusiform masses eccentrically located with the involved nerve and are contained within the epineurium.

The typical magnetic resonance (MR) appearance is iso-to-hyperintense (compared to muscle) on T1-weighted images, hyperintense on fluid-sensitive sequences, and often diffusely enhancing on contrast-enhanced images.[1] Tissue heterogeneity is relatively common, particularly cystic degeneration. When present, heterogeneity has been shown to correlate histologically with a greater ratio of Antoni B tissue than Antoni A. On MR imaging (MRI), Type 1 predominant tumors tend to be small and homogeneous while heterogeneous tumors (with or without cystic degeneration) tend to have higher proportions of Type 2. Larger and more heterogeneous tumors also demonstrate increased hemosiderin deposits and may be referred to ancient schwannomas.[23] Malignant degeneration of schwannomas is exceedingly rare.

In this pictorial review, we present a spectrum of schwannomas that arise in peripheral nerves in different regions of the body from head to toe. The illustrative cases were collected from two institutions (National University Hospital, Singapore and Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA) from January 2003 to December 2015. All cases are pathology proven, except for those patients with multiple schwannomas when an earlier excised tumor was pathology-proven schwannoma.

HEAD AND NECK SCHWANNOMAS

Approximately 45% all schwannomas occur in the head and neck region arising from peripheral, cranial, or autonomic nerves [Figures 1–6]. Clinical symptoms typically correlate with distribution of the involved nerve though this may be confounded by size and location of the mass. The vestibulocochlear nerve is most commonly involved, accounting for 6%–8% of all intracranial tumors and 80% of cerebellopontine angle tumors. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas are commonly seen in NF Type 2. In the rare cases of malignant nerve sheath tumors, approximately 20% occur in the head and neck. Poor prognostic factors include tumor (size >5 cm), presence of NF, and incomplete resection.[4]

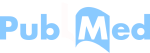

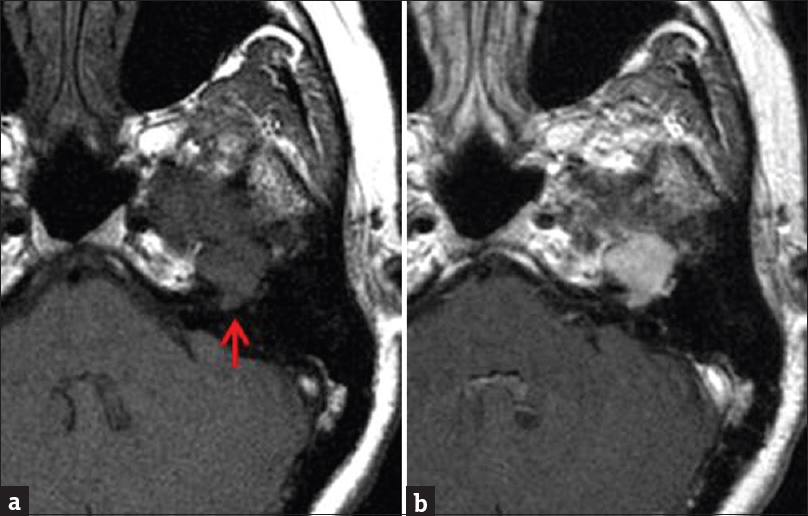

- Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with clinical diagnosis of neurofibromatosis Type 2. (a) Axial T2-weighted sequence demonstrates small bilateral isointense vestibular masses (arrows). (b) Enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates enhancement of the masses. Right-sided mass is larger, causing mild expansion of the internal acoustic canal and an “ice-cream cone” appearance. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas are most commonly seen in patients with neurofibromatosis Type 2.

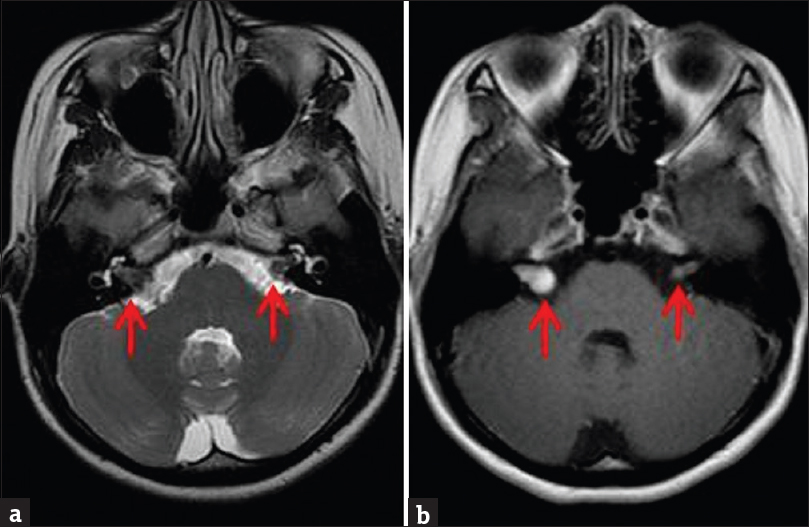

- Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging. (a) Axial T2-weighted sequence demonstrates a right vestibular mass with high T2 signal correlating with areas of cystic degeneration (arrow). (b) Enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates mild heterogeneous enhancement of the solid portions of the mass, with low T1 signal correlating with the cystic component (arrow).

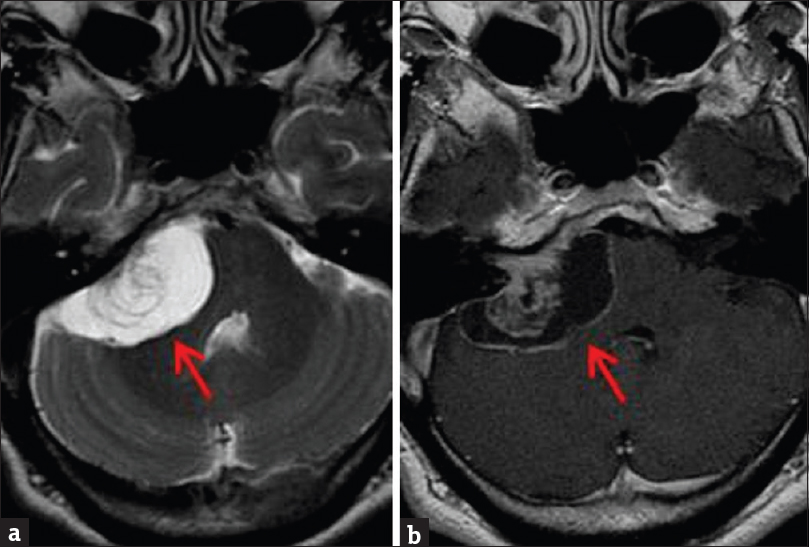

- Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging. (a) Axial T2-weighted sequence demonstrates large hyperintense left vestibular mass with extension into the internal auditory canal. Note a high T2 signal cerebrospinal fluid cleft laterally (arrow). (b) Enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates heterogeneous mass enhancement.

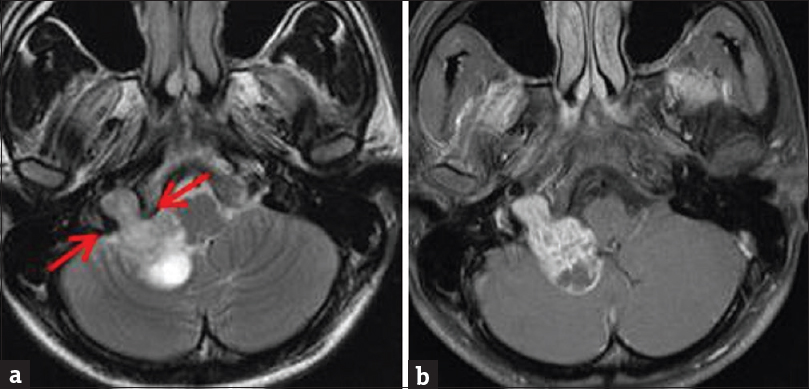

- Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging. (a) Unenhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates T1 isointense mass along the course of the infratemporal portion of the left facial nerve (arrow). (b) Enhanced axial T1-weighted sequence demonstrates fairly homogeneous mass enhancement.

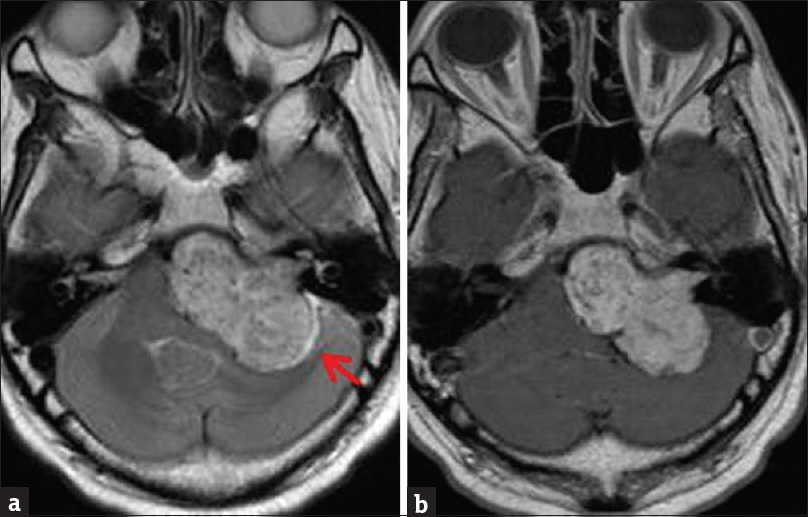

- Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging. (a) Axial T2-weighted sequence demonstrates iso-to-hyperintense dumbbell-shaped mass extending across the right jugular foramen (arrows) into the posterior cranial fossa. (b) Enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates heterogeneous enhancement.

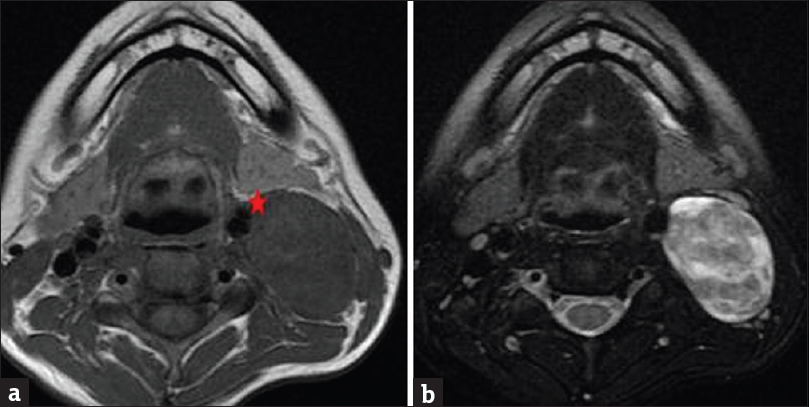

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the neck without contrast. (a) Axial T1 sequence demonstrates large fusiform isointense mass within the left carotid sheath at level of the angle of the mandible. The mass displaces the carotid artery anteromedially (star). (b) Axial T2-weighted sequence demonstrates heterogeneous T2 signal, with areas of higher signal correlating with cystic degeneration.

Spinal schwannomas

Schwannomas and neurofibromas represent 25%–30% of intraspinal masses. They may be intradural (70%–75%), extradural (15%), or combined intradural/extradural (15%), referred to as a dumbbell tumor.[5] Clinical presentation varies depending on the site of involvement, but pain and paresthesias are the most commonly reported symptoms [Figures 7–10].

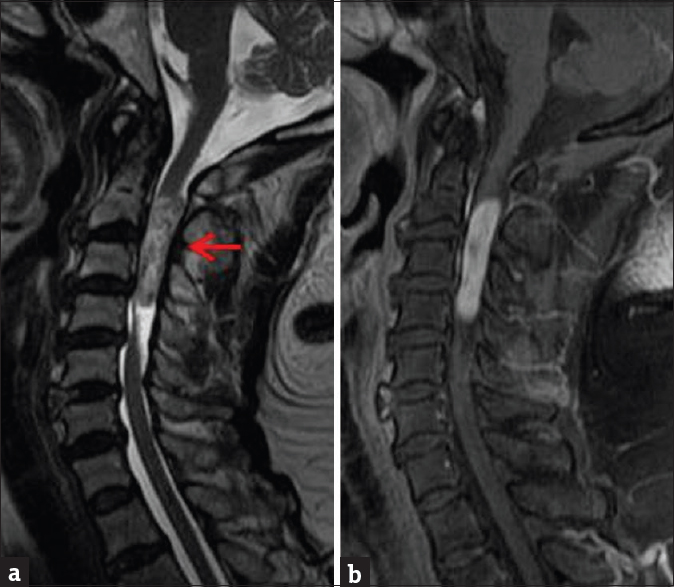

- Contrast-enhanced cervical spine magnetic resonance imaging. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted sequence demonstrates heterogeneously T2 hyperintense intramedullary mass extending from C2-C4 spinal segments. (b) Enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates nearly homogeneous mass enhancement. Pathology was consistent with schwannoma.

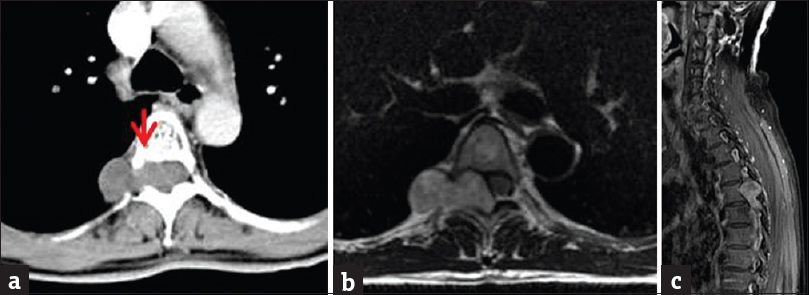

- Contrast-enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine. (a) Axial contrast-enhanced CT image demonstrating a classic dumbbell-shaped mass with the waist located at the right T5/T6 neural foramen. Note the scalloping of the posterior aspect of the vertebral body (arrow).(b) Axial T2-weighted sequence demonstrates similar findings with isointense T2 mass signal. (c) Sagittal enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates heterogeneous mass enhancement.

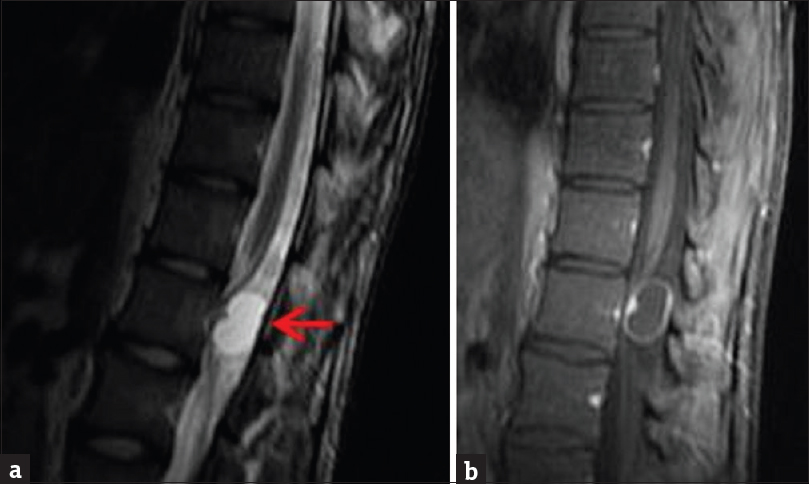

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine. (a) Sagittal T2-weighted sequence demonstrates a small mass in the upper lumbar spine with primarily high T2 signal, consistent with cystic degeneration (arrow). (b) Enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates mild enhancement of the noncystic portions of the mass.

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis. (a). Axial T2-weighted fat-saturated sequence demonstrates hyperintense presacral mass arising from a left sacral foramen and extending into the pelvis causing mass effect.(b) Enhanced spoiled gradient-recalled sequence demonstrates intense heterogeneous mass enhancement. Pathology was consistent with schwannoma.

INTRA-ABDOMINAL SCHWANNOMAS

Intra-abdominal schwannomas [Figures 11 and 12] are uncommon, with the stomach being the most frequent site. Colorectal and retroperitoneal schwannomas are very rare. Diagnosis is difficult preoperatively and usually requires surgical excision. These tumors are often discovered incidentally on imaging but may present with nonspecific symptoms depending on location and size. On imaging, intra-abdominal schwannomas may be very difficult to differentiate between the more common gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors (i.e., leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumor [GIST]).[6]

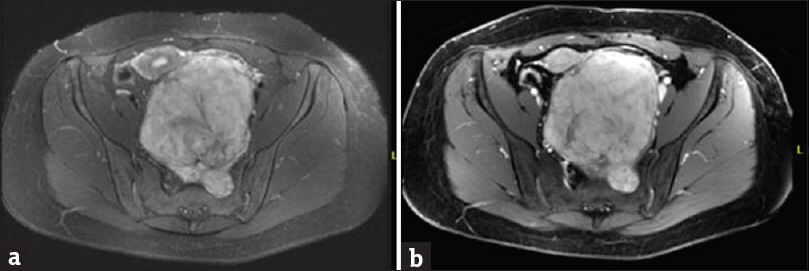

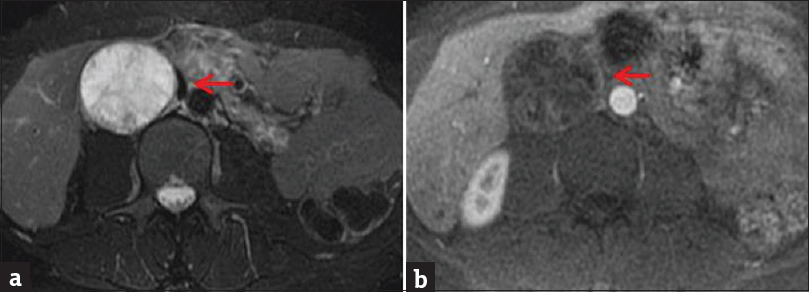

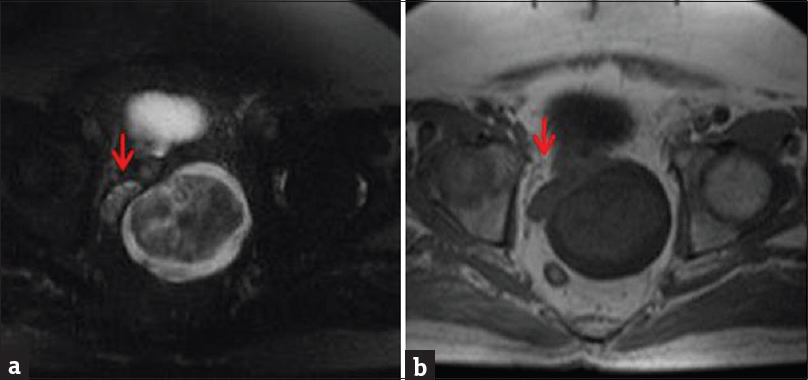

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the abdomen. (a) Axial T2-weighted fat-saturated sequence demonstrates large, round primarily T2 hyperintense retroperitoneal mass (arrow). (b) Enhanced axial T1-weighted sequence demonstrates striations and peripheral rim-like enhancement (arrow). Lack of significant enhancement suggests cystic degeneration, which also correlates with the high T2 signal. Pathology consistent with schwannoma and also confirmed cystic degeneration.

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis without contrast. (a) Axial T2-weighted fat-saturated sequence demonstrates nonspecific enlargement of the left seminal vesicle by a mass with both cystic (high T2) and solid (isointense T2) components. The normal right seminal vesicle can be seen for comparison (arrow). (b) Axial T1-weighted sequence low T1 signal of the mass.

THORACIC SCHWANNOMAS

Intrathoracic schwannomas can arise from any thoracic nerve, but they are most often found in the middle or posterior mediastinal compartments. Most commonly they arise from a spinal nerve root, intercostal nerve [Figure 13], or the brachial plexus and extend into the thoracic cavity. Schwannomas arising from the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves have also been reported. MRI is essential before surgical intervention to evaluate for intraspinal extension because the operative approach may differ. In 50% of cases, erosion/deformity of ribs, vertebral bodies, and neural foramina can be seen.[7]

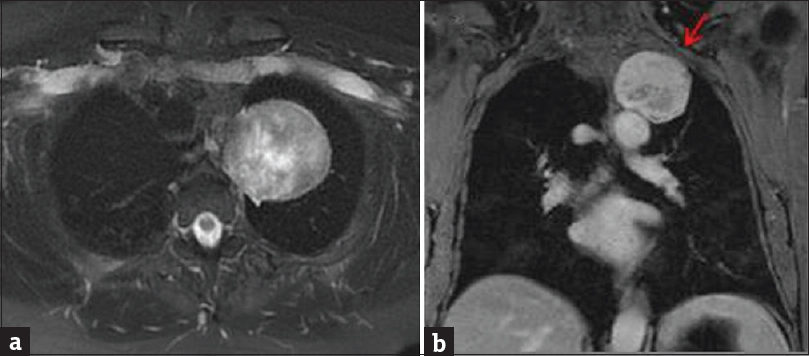

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the chest. (a) Axial T2-weighted fat-saturated sequence demonstrates well-circumscribed, heterogeneously T2 hyperintense, extrapulmonary mass in the left lung apex. (b) Coronal enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates heterogeneous enhancement, with smooth remodeling of the left 2nd rib (arrow). At surgery, this mass was closely associated with an intercostal nerve. Pathology was consistent with schwannoma.

Extremity schwannomas

Schwannomas are the most common solitary tumor of the peripheral nerve [Figures 14–19]. They typically present as a slow-growing firm round mass with paresthesias of the associated nerve distribution. In the upper extremities, flexor surface is the most common location due to the presence of large nerves. Due to their eccentric location, these tumors can often be excised with preservation of nerve function.[8]

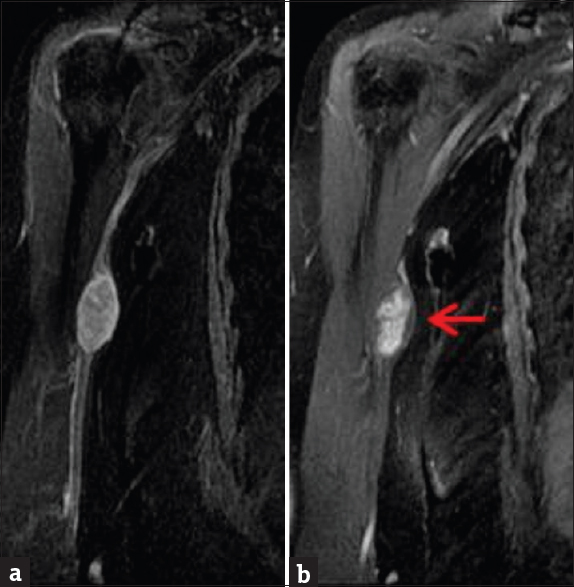

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the right humerus. (a) Coronal enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates a well-defined ovoid heterogeneously enhancing mass in the medial aspect of the right arm. (b) Short inversion time inversion recovery sequence demonstrates the same mass (arrow), eccentrically located in relation to the right ulnar nerve.

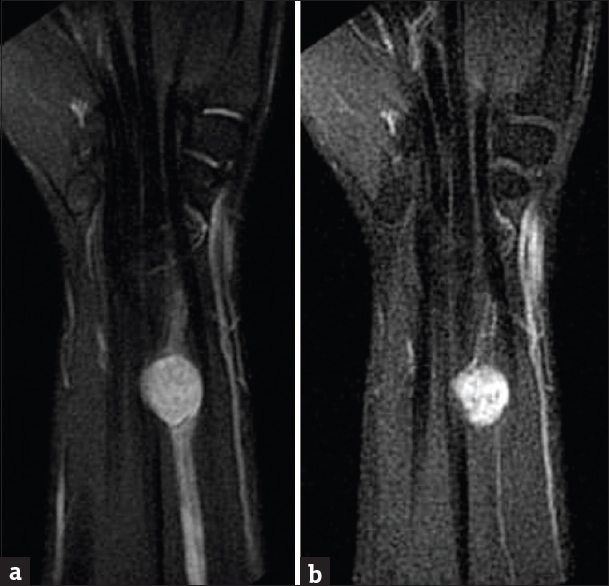

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the right wrist. (a) Coronal T2-weighted sequence demonstrates round, T2 hyperintense mass just proximal to the wrist joint in close relation to the median nerve. (b) Enhanced T1-weighted images demonstrate nearly homogeneous mass enhancement.

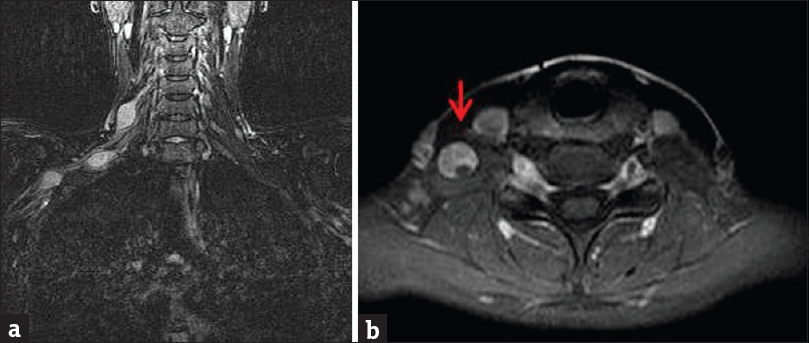

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the right brachial plexus. (a) Coronal short inversion time inversion recovery sequence demonstrates several T2 hyperintense ovoid schwannomas arising from the right brachial plexus. (b) Axial enhanced T1-weighted MR images demonstrate heterogeneous mass enhancement (arrow).

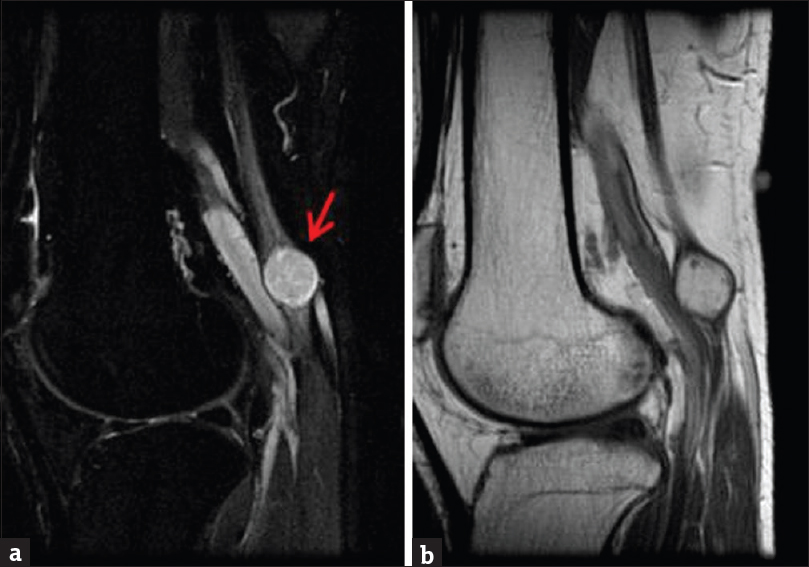

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the right knee with attention to the popliteal fossa. (a) Sagittal short inversion time inversion recovery sequence demonstrates round T2 hyperintense mass closely associated with the tibial nerve (arrow). (b) Sagittal enhanced T1-weighted sequence demonstrates nearly homogeneous mass enhancement.

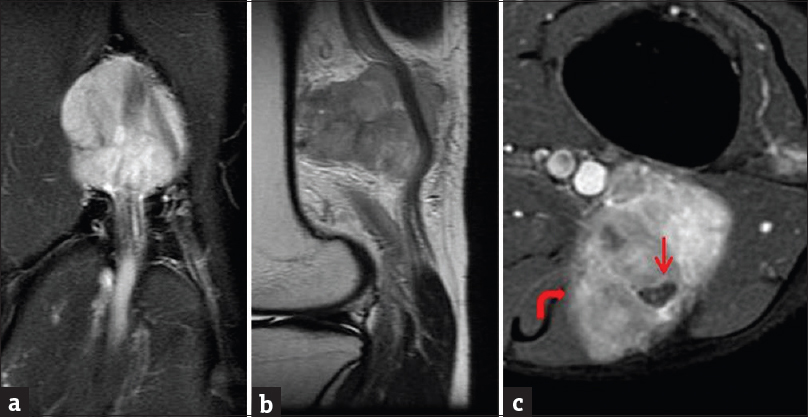

- Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the left knee with attention to the popliteal fossa. (a) Coronal short inversion time inversion recovery sequence demonstrates large T2 hyperintense mass in the popliteal fossa. (b) Sagittal T1-weighted sequence demonstrates the T1 isointense mass closely related to the sciatic nerve. (c) Enhanced axial T1-weighted sequence demonstrates heterogeneous mass enhancement, with encasement of the sciatic nerve. Note the ill-defined medial margin (curved arrow); focal malignant degeneration was seen on histology.

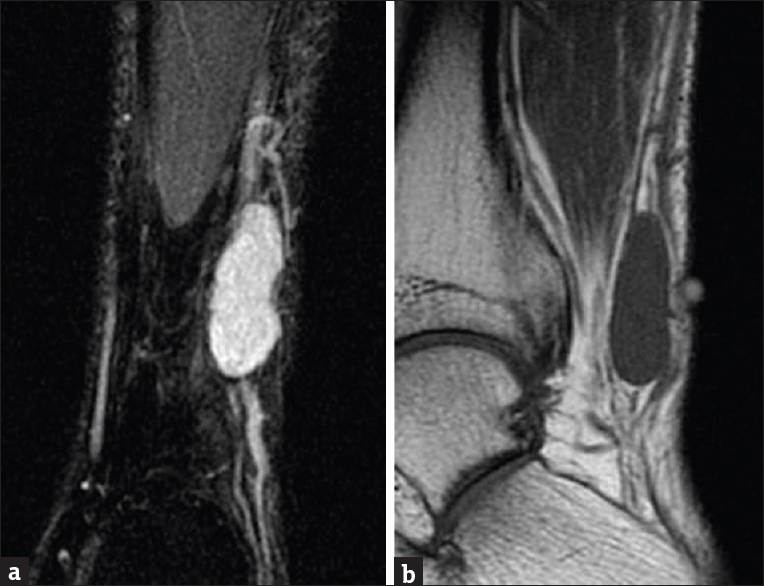

- Magnetic resonance imaging of the left ankle without contrast. (a) Coronal short inversion time inversion recovery sequence demonstrates well-defined T2 hyperintense fusiform mass at the lateral aspect of the ankle closely related to the sural nerve. (b) Sagittal T1-weighted sequence demonstrates isointense T1 signal of the mass.

DISCUSSION

Schwannomas demonstrate typical MRI features of T1 iso-to-hypointensity, T2 hyperintensity, and postcontrast enhancement. Heterogeneous signal intensity and postcontrast enhancement are suggestive of internal hemorrhage and myxoid/cystic changes. There are additional imaging and pathological features which suggest the diagnosis of schwannomas; however, they are not specific for schwannomas and also may be present in other neurogenic tumors including neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. The entering and exiting nerve sign describes the presence of a peripheral nerve coursing in and out of the mass.[1] This can be seen on pathological analysis and may or may not be seen on imaging depending on the size of the mass. The target sign consists of low/intermediate T2 signal centrally (fibrous tissue), with high T2 signal peripherally (myxoid tissue).[1] The fascicular sign represents multiple ring-like structures, corresponding to fascicular bundles also seen in cross section of normal nerves.[1] A secondary sign that may suggest a neurogenic neoplasm is muscle atrophy within the nerve distribution.[1]

Distinguishing benign schwannomas from malignant soft-tissue tumors can be challenging and often may not be possible. Features that favor malignant transformation include ill-defined margins and larger size (>5 cm).[910] Features that should favor schwannoma over malignant soft-tissue tumors include the split fat sign (rim of fat surrounding the tumor), the bright rim sign (high T2 signal at the periphery of the mass), absence of lobular shape (defined as <2 or more deep lobulations), lack of extensive peritumoral edema (extensive defined as >18 mm), and a defined capsule.[10] These findings are reliable for schwannoma if two or more coexist.

CONCLUSION

While common MRI characteristics for schwannomas exist, diagnosis by imaging alone remains challenging. Recognizing described imaging patterns for schwannomas can help narrow down a differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses, especially in unexpected locations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Swee Tian Quek, Diagnostic Imaging, National University Hospital, NUHS, Singapore, for his assistance in obtaining images for this pictorial review.

Available FREE in open access from: http://www.clinicalimagingscience.org/text.asp?2017/7/1/38/215898

REFERENCES

- From the archives of the AFIP. Imaging of musculoskeletal neurogenic tumors: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:1253-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vestibular schwannomas: Correlations between magnetic resonance imaging and histopathologic appearance. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:79-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuropathology for the neuroradiologist: Antoni A and antoni B tissue patterns. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1633-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current management of head and neck schwannomas. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:117-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pictorial essay: Diverse imaging features of spinal schwannomas. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:329-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intraabdominal schwannomas: A single institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:756-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary mediastinal tumors: Part II. Tumors of the middle and posterior mediastinum. Chest. 1997;112:1344-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer. 1986;57:2006-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- MR imaging differentiation of malignant soft tissue tumors from peripheral schwannomas with large size and heterogeneous signal intensity. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:940-6.

- [Google Scholar]